Four key antitrust events in Q4 2021 target labor markets and aim to protect workers: Here's what you need to know

15 min read

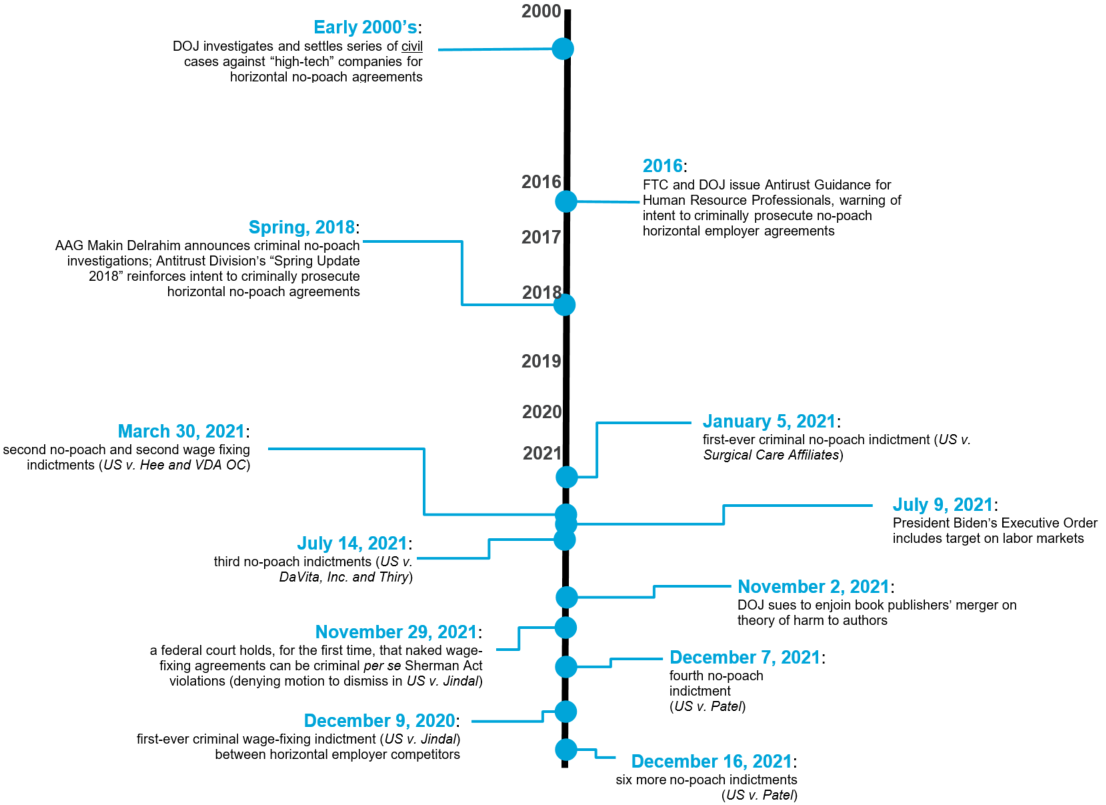

The focus on using the antitrust laws to target labor markets has been gaining momentum for years, but the close of 2021 saw the trend hit overdrive with antitrust attacks on perceived harm to workers coming from all corners of the legal landscape, including from the federal courts, the antitrust enforcement agencies, and the White House.

What happened: Four antitrust events targeting labor practices

1. November 2, 2021: The Department of Justice's Antitrust Division filed to block publishing house merger based on a theory of harm to authors, does not allege merger will result in increased prices.

On November 2, 2021, the Antitrust Division filed suit in DC federal district court to block Penguin Random House's proposed acquisition of Simon and Schuster.1 The Antitrust Division's leading theory of harm is that this merger would result in lower monetary advances and royalties paid to authors. Essentially, the Antitrust Division argues, the merged publishing house would have such increased buying power vis-à-vis authors that authors would lose the ability to negotiate fair wages (which, in the publishing industry, come in the form of advances and royalties).

While the Antitrust Division's complaint briefly mentions consumer welfare—alleging that decreased payments to authors will eventually lead to fewer authors and decreased literary choice for consumers—the complaint is silent on how the merger could impact consumer prices. The Division's move to block the book publishers' merger on the harm-to-authors theory that declines to even allege the historically key antitrust harm—increased prices—is therefore emblematic of the Biden Administration's and the new populist antitrust movement's push to direct the purpose of antitrust away from consumer welfare price effects and towards other social harms.

Why this matters

How the Division approaches the merger and then how the court applies the law in this case could be an important signal in the direction of future antitrust merger enforcement. In the past, the Antitrust Division's attempts to block mergers have failed when its economists could not clearly establish that the transaction would have a negative impact on price.2 And since no legislation has yet been passed to change the language or application of the Sherman Act, the price effects-driven consumer welfare standard established by decades of case law is likely to continue to be guiding, if not binding, precedent. This case will be one to watch for its treatment of the consumer welfare standard and for its treatment of buying power.

2. November 29, 2021: For the first time ever, a federal court held that wage fixing between horizontal competitors can be a per se and criminal violation of the antitrust laws.

On November 29, 2021, a federal district court held for the first time that a conspiracy to fix wages can constitute a per se criminal violation of the Sherman Act.

The Antitrust Division first indicted the defendants, the owner of a physical therapist staffing company and an employee, in December of 2020, alleging that they had made agreements with competitor companies, including over text message, to lower pay rates for therapists.3 The defendants moved to dismiss the charges, arguing that wage fixing was not equivalent to price fixing, and thus could not constitute a per se violation.4 The defendants also argued that because "wage fixing" had never before been prosecuted as a per se violation, they lacked "fair warning" that their conduct was criminal, and the indictments therefore violated their due process rights.5

In its recent decision, the US District Court for the Eastern District of Texas disagreed on both fronts in the posture of a motion to dismiss the indictment. The Court held that "any naked agreement among competitors—whether by sellers or buyers—that fixes components that affect price meets the definition of a horizontal price-fixing agreement."6 The Sherman Act, the court held, applies to buyers of goods and services, and buyers of services includes employers in the labor market.7 The alleged wage-fixing agreement was "plainly anticompetitive and has no purpose except stifling competition."8 The court stated that "[w]hen the price of labor is lowered, or wages are suppressed, fewer people take jobs, which ‘always or almost always tend[s] to restrict competition and decrease output.'"9 Whether low wages means more persons are offered employment appears not to have been considered by the court.

The court firmly rejected the defendants' due process argument for the same reasons it had rejected their argument that there was no per se violation: according to the court, wage fixing is a form of price fixing, which is a well-established criminal violation.10

Why this matters

This is the first time that a wage-fixing agreement between horizontal competitors has been held to be grounds for a criminal antitrust violation. Wage-fixing cases have historically been prosecuted in the civil context, meaning fines for companies and individuals. The expansion of Sherman Act criminal violations changes the ball game when it comes to how companies engage with their workers—if this decision stands (i.e., if it is not overturned on appeal), executives and managers could face jail time for proven horizontal wage-fixing conspiracies.

3. December 7, 2021: The White House's Tim Wu commented that misclassifying workers as contractors instead of employees could be an antitrust violation.

On December 7, 2021, Special Assistant to the President Tim Wu gave the introductory remarks at the Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission's jointly hosted Public Workshop on Promoting Competition in Labor Markets. In his short speech, Wu explained that the White House feels that the American public demands more action to control market power and make the economy "feel fair." Wu emphasized that part of this "fairness" requires that low-wage workers have the ability to change jobs and negotiate for better work and higher wages.

Wu laid out four areas where he believes antitrust regulation of the labor market matters. The first three areas where Wu saw opportunity for antitrust to be used to regulate labor markets—(1) in the regulation of vertical mergers, (2) in the scrutiny on monopsonies (that is, buyer-side monopolies); and (3) in antitrust enforcement of franchises—were not unexpected based on prior Administration statements.

Wu's fourth comment, however, is quite noteworthy insofar as it contemplates antitrust scrutiny (if not vulnerability) for decisions involving independent contractors (practices usually governed by state and federal labor and tax laws and guidance):

". . . some of the contracts and relationships that may be set up to avoid classifying someone as an employee should be carefully examined for legality under the antitrust laws."

Wu stated that while worker classification is "complex," misclassification is a "shadow over this area." The context of Wu's remarks indicate that one of the White House's chief concerns is that "gig workers" are not currently able to unionize. When workers are classified as employees, the employer receives a certain level of control and the employee qualifies for certain, legally required benefits, and one key benefit is that employees are entitled to participate in collective bargaining efforts (which are exempt from antitrust scrutiny).11 Collective bargaining is intended for workers to organize and lobby for better positions for themselves, such as for higher wages, increased benefits, and better working conditions. Independent contractors, however, cannot legally participate in these activities. Tim Wu was not clear in his remarks what specific types of contracts or whether "vertical" agreements (rather than horizontal agreements among horizontal competitors) were the focus of his remarks.

Why this matters

The battle for employee classification is currently playing out worldwide with gig economy companies, like ridesharing and delivery apps, pushing to maintain their drivers' status as contractors.12 State and city-led actions to allow collective organization of ride-hailing contractors has been met with significant pushback from the ride-hailing companies and some public officials.13 Worker classification has historically been the subject of labor laws, with some overlap with tax and other regulatory law, but Wu's remarks argue for antitrust to be a tool in worker-classification enforcement, too. Notably, Wu's interpretation of the Sherman Act to address worker misclassification requires no new legislation at the state or federal level, if courts were to somehow fit it into existing decisional law. Wu's point, taken to the next logical step, is that the Sherman Act could already be read to ban worker misclassification that harms workers; certainly no court has held this yet, nor is known to have been asked to hold that yet.

4. December 7 and December 16, 2021: The Antitrust Division brought 6 additional "no-poach agreement" indictments, bringing its total to 12 ever, all in 2021.

On December 7, 2021, for only the fourth time ever, the Antitrust Division announced a criminal indictment for a so-called "no-poach" agreement between horizontal competitors. A former director of global engineering at a major aerospace engineering company was indicted for allegedly conspiring with outsource engineering suppliers to restrict recruiting and hiring of engineers and other skilled workers.14 The newly unsealed affidavit in support of the criminal complaint and arrest warrant alleges that an unnamed aerospace company would seek outside engineers for particular projects, and several companies competed to supply those engineers.15 Patel, the director for the unnamed company who was in charge of managing the relationship with the supplier companies, allegedly made agreements with the suppliers to allocate employees by restricting hiring and recruiting between the companies from approximately 2011 through 2019.16 Patel allegedly specifically instructed managers at the supplier companies not to recruit each other's employees.17

This is the fourth anti-poaching case the DOJ has brought within the last calendar year, and the DOJ indicated in its press release that this was only the "first" indictment brought in this ongoing investigation.18 According to the affidavit in support of the criminal complaint, six unnamed companies and eight individual co-conspirators were allegedly involved in Patel's alleged anti-poaching conspiracy, so more indictments could be on the way.19

On December 16, 2021, true to its word, five additional aerospace executives and managers were also indicted for "leading roles in labor market conspiracy that limited workers' mobility and career prospects."20

Why this matters

The aerospace indictments bring the Antitrust Division's total "no-poach" agreement between horizontal competitors indictments to 9 individuals and 3 companies—signaling that the agency has a strong focus to continue criminally prosecuting this conduct going forward.

Why it is happening: These events are in line with increasing antitrust focus on labor markets

Enforcement in the labor markets has been gaining steam over the last decade.21 About ten years ago, the Antitrust Division investigated several "high tech" companies for so-called anticompetitive "no-poach agreements" wherein the companies allegedly agreed not to hire, or "poach" each other's employees. Many of these cases ended in settlements and civil consent decrees—none were criminal.

In the wake of the high-tech no poach cases, in 2016, the Antitrust Division and the FTC issued a joint Antitrust Guidance for Human Resource Professionals, which warned that the DOJ intended to "proceed criminally against naked wage-fixing or no-poaching agreements" between horizontal employers.22 And in 2018, former Assistant Attorney General of the Antitrust Division, Makin Delrahim, announced that the Division was actively working on several criminal antitrust cases against horizontal employer competitors who allegedly had agreements not to poach one another's employees.23 The Antitrust Division reiterated AAG Delrahim's report in its "Spring Update 2018" which reinforced the Division's intent to proceed criminally against no-poach agreements between horizontal employer competitors.24

The focus on labor markets started to gain pace in 2020—now-FTC Chair Lina Khan and then-FTC Commissioner Rohit Chopra penned an article advocating for enhanced federal agency rulemaking and highlighting anticompetitive practices in labor markets as an area well-suited for this approach. Moreover, just before the close of 2020, in December, the DOJ filed its first-ever criminal antitrust prosecution with wage-fixing allegations between horizontal employer competitors.

But in the past year, this move to focus on labor agreements has really taken off.

In January 2021, the Antitrust Division filed its first-ever criminal antitrust prosecution with no-poach allegations between horizontal employer competitors, and the Division followed with its second and third criminal "no-poach" indictments in March and July

Also in July 2021, President Biden issued Executive Order 14036, Promoting Competition in the American Economy, which included 72 initiatives aimed at enhancing competition in the US. (See our analysis of the Executive Order's impact on non-compete agreements here.25) One of those initiatives is combating anticompetitive practices in the labor markets, and the Executive Order explicitly encourages the FTC to consider whether to ban or limit the use of employer non-compete agreements with employees.26 Shortly thereafter, on July 14, 2021, the Antitrust Division achieved its third and fourth-ever indictments for no-poach agreements between horizontal competitors.27

The four recent events that are the subject of this article are a culmination of this momentum—and likely a signal that the focus of antitrust enforcement on harm to labor markets is a theme that is here to stay.

Enforcement in labor markets has been increasing over time, but 2021 saw the most concentrated focus yet.

What companies can do about it

Follow the news on the pending antitrust labor cases.

How the antitrust laws are being used to enforce inequalities in labor markets is a quickly changing landscape. Indeed, as discussed in this article, three of the four recent events are novel (the Antitrust Division seeking to block a merger on a harm-to-worker theory without reference to potential increased prices; a criminal wage-fixing case survives a motion to dismiss for the first time ever; the White House's Tim Wu suggests that antitrust be used to combat worker misclassification)—and these events just happened.

Now is a good time to update your antitrust compliance.

Government priorities are ever-changing. With the theme of analyzing conduct's effects on workers becoming an even hotter topic, now is the time to build compliance and reporting strategies to ensure the laws are followed across your organization. Antitrust compliance policies even a handful of years old could be critically out of date.

As a threshold matter, looking again at how corporate antitrust policy impacts any communication with any competitor should be an ongoing function within the legal/compliance apparatus. Communications about pricing and geography/markets are already precluded by most companies' policies, but companies should consider adding prohibitions against discussions with competitors about salary and poaching as well.

With respect to employment agreements, companies should consider a fresh look at several aspects of employment/HR practices, such as: the use of and business justification for any no-poach clauses; the use of and business justification for non-compete clauses in employment contracts and company policies; and the involvement of the legal department in documenting decision-making around the engagement of independent contractors, not only from tax and labor perspectives but with an eye towards the emerging antitrust perspective as well. Companies should also consider a holistic review of the potential antitrust impact that ESG policies can have if adopted out of context.

Document deals' pro-competitive effects on workers, document pro-competitive justifications for employee decisions.

If the enforcement agencies are going to continue to be more and more critical of deals that could negatively affect workers, companies considering transactions should see this as an opportunity, too, and should be proactive about documenting and demonstrating the positive effects that a deal could have on employees or workers. Similarly, companies making unilateral business decisions that could adversely affect workers should carefully examine, and carefully document, their pro-competitive justifications, should they ever be called into question down the road.

1 DOJ Antitrust Division Press Release, Justice Department Sues to Block Penguin Random House's Acquisition of Rival Publisher Simon & Schuster (Nov. 2, 2021).

2 See, e.g., United States v. AT&T, Inc., 916 F.3d 1029 (D.C. Cir. 2019).

3 United States v. Jindal, No. 4:20-CR-00358, 2021 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 227474, at *3-4 (E.D. Tex. Nov. 29, 2021).

4 Id. at 11.

5 Id. at 28.

6 Id. at 13.

7 Id. at 14.

8 Id. at 17.

9 Id. at 21 (quoting Bus. Elecs. Corp. v. Sharp Elecs. Corp., 485 U.S. 717, 723 (1988)).

10 Id. at 29.

11 29 U.S. Code § 157 (2021).

12 See, e.g., Matter of Lowry (Uber Tech., Inc.—Comm'n of Labor), 189 A.D. 3d 1863, 1865 (Dec. 2020); Margot Roosevelt, Prop. 22 is ruled unconstitutional, a blow to California gig economy law, LA Times (Aug. 20, 2021); Anthony Deutsch, Uber drivers are employees, not contractors, says Dutch court, Reuters (September 13, 2021).

13 See, e.g., Heidi Groover, Lengthy legal fight over Seattle's Uber Unionization law comes to an end, Seattle Times (April 13, 2020).

14 U.S. v. Patel, 3:21-mj-01189 (D. Conn., Dec. 7, 2021); Press Release, Dep't of Justice, Former Aerospace Outsourcing Executive Charged for Key Role in a Long-Running Antitrust Conspiracy (Dec. 9, 2021).

15 Affidavit In Support Of Criminal Complaint and Arrest Warrant, U.S. v. Patel, 3:21-mj-01189, at ¶¶ 5-6 (D. Conn., Dec. 9, 2021), ECF No. 15.

16 Id. at ¶¶ 7, 11.

17 Id. at ¶ 16.

18 Press Release, Dep't of Justice, Former Aerospace Outsourcing Executive Charged for Key Role in a Long-Running Antitrust Conspiracy (Dec. 9, 2021).

19 Affidavit In Support Of Criminal Complaint and Arrest Warrant, U.S. v. Patel, 3:21-mj-01189, at ¶¶ 6, 8 (D. Conn., Dec. 9, 2021), ECF No. 15.

20 Press Release, Dep't of Justice, Six Aerospace Executives and Managers Indicted for Leading Roles in Labor Market Conspiracy that Limited Workers' Mobility and Career Prospects (Dec. 16, 2021).

21 See also, Kuhn, Sakellariou-Witt, Gidley, Mims, Paul, Powell, Caroppo, Citron, No-Poach agreements on the European Commission dawn raid radar (Nov. 8, 2021)

22 U.S. Dep't of Just. & Fed. Trade Comm'n, Antitrust Guidance for Human Resource Professionals (October 2016).

23 Matthew Perlman, Delrahim Says Criminal No-Poach Cases Are In The Works, Law360 (Jan. 19, 2018).

24 Division Update Spring, 2018.

25 Gidley, Mims, O'Shaughnessy, McNamee, Adam, Phillips, Marnin, Analysis: FTC Encouraged to Ban or Limit Non-Compete Agreements in July 9, 2021 Executive Order; Breaks with Tradition and Follows Trend of Antitrust Enforcement on Labor Markets (July 19, 2021)

26 Exec. Order No. 14036, 86 Fed. Reg. 36987, Promoting Competition in the American Economy, § 5(g) (July 9, 2021).

27 Indictment, U.S. v. DaVita, Inc. and Thiry, 1:21-cr-00229 (D. Colo. July 14, 2021).

This publication is provided for your convenience and does not constitute legal advice. This publication is protected by copyright.

© 2022 White & Case LLP