As momentum builds around the transformative role hydrogen could play in the clean energy transition, we examine the unique opportunities open to market players in Asia-Pacific. This is the third and final article in our hydrogen economy series.

Hydrogen Economy Series: Part 3

In Parts 1 and 2 of this Series, we outlined the key concepts and applications underpinning "the hydrogen economy" and analysed the state of play in Asia-Pacific.

In this third and final Part, we examine a hypothetical project development and financing, and set out some key legal considerations relevant to hydrogen.

Introduction

Concepts of the ideal 'hydrogen economy' vary, and hydrogen has multiple applications in several varied industries (see Parts 1 and 2 for our insights).

However, most interest generated has been in respect of clean hydrogen, whether it be 'green' or 'blue' hydrogen. For our case study, we have chosen to consider a hypothetical value chain involving the production and sale of green hydrogen (however, we note several of the issues raised would also be relevant to projects involving the production of hydrogen via other methods).

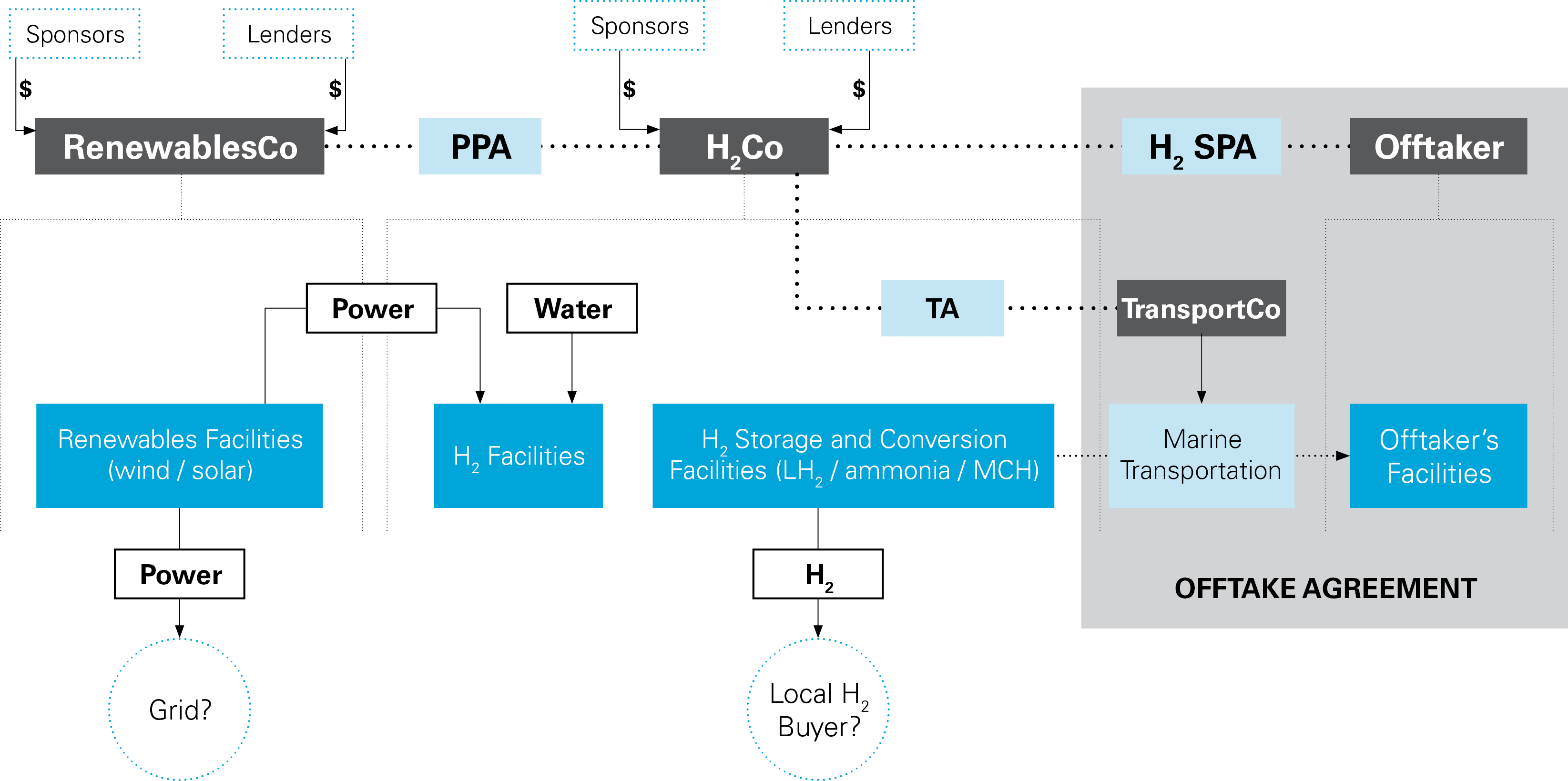

In summary, our hypothetical hydrogen project would involve:

- a special purpose company (H2Co) established for the purpose of developing and operating the project, whose activities would be funded through a mix of equity investment and project finance;

- the production of green hydrogen at a hydrogen production facility owned by H2Co, using an electrolyser to be constructed as part of the facility;

- the supply of renewable electricity to H2Co from an adjacent wind or solar facility owned by RenewablesCo via a power purchase agreement;

- facilities, adjacent to the hydrogen production facilities and also owned by H2Co, for conversion of the hydrogen to a more efficiently transportable form such as liquefied hydrogen, ammonia or methylcyclohexane (for simplicity, these transportable derivative forms are referred to as hydrogen product);

- an offtake agreement (H2 SPA) to be entered into between H2Co and Offtaker, under which Offtaker agrees to purchase the green hydrogen product from H2Co; and

- transportation arrangements with TransportCo in order to transport the hydrogen product from its production point to the Offtaker's preferred destination.

Project development and structure

The structure outlined above is a power supply or 'split' model, whereby RenewablesCo owns the renewable power assets (the Renewables Facilities) and supplies green electricity to H2Co, which owns the hydrogen production, liquefaction/conversion, storage and loading facilities (H2 Facilities). Under this model, the same or different sponsors could own RenewablesCo and H2Co. This would also potentially allow for separate financings of renewables assets and the hydrogen assets.

This is merely one of many ways to structure hydrogen projects. For example, a different structure could be an integrated model, which would involve a single entity owning both the Renewables Facilities and the H2 Facilities. An integrated model would be less flexible in terms of enabling different sponsors to own different parts of the overall project, to exit different parts at different times or undertake separate financings. However, the integrated structure may simplify financing and risk allocation. Ultimately, the unique circumstances of each project, including commercial, financing and tax considerations (including any available subsidies and tax incentives), will dictate the preferred project structure.

Construction phase

For the purpose of our 'split model' case study, we will assume that a lump sum turnkey engineering, procurement and construction (EPC) contract would be entered into by H2Co and an EPC contractor with respect to the H2 Facilities, with ownership in the assets to pass to H2Co upon completion. Separately, RenewablesCo would have construction and supply contracts with respect to the Renewables Facilities (Renewables EPC).

Assuming the facilities are to be constructed and/or located together, H2Co, RenewablesCo and the respective EPC contractors will likely need to enter into an interface agreement to address the interface risks arising between these projects during the construction, commissioning and operations phases. This interface agreement will cover any physical site interfaces between the Renewables Facilities and the H2 Facilities, and should also address indemnities in respect of any damage or other liabilities that may arise as a result of the interface works.

If an integrated model is used instead, it would in theory be more possible to have a single EPC contractor for the entire project, providing a "wrap" in respect of the construction of H2 Facilities and the Renewables Facilities. However given the different nature of such facilities, it is not clear that as a practical matter such a wrap could be obtained on terms that are economically feasible for the project.

Operations and maintenance phase

Assuming a standard turnkey approach is taken in the construction phase, H2Co would enter into a separate operations and maintenance (O&M) agreement with a contractor capable of operating and maintaining the H2 Facilities.

In typical O&M agreements, the negotiation of appropriate pricing for the O&M services is crucial. Here, H2Co (and its lenders) would need to take into account several factors including the lifespan of the assets, applicable site conditions, relevant environmental factors and the quality requirements stipulated under the EPC contract.

The evolving nature of hydrogen technology presents additional complexities for O&M arrangements. For this reason, it is important that key contractual provisions dealing with system maintenance and warranty issues are agreed upfront with the equipment manufacturer, especially given the specialised nature of the relevant components. When negotiating O&M pricing, project developers should be aware of cost savings that may emerge as a consequence of technological improvements.

The servicing arrangements for the Renewables Facilities will also need to be considered, particularly if an integrated model is adopted. However, given these arrangements are comparatively well-established in the market, the relevant issues will likely be less complex than in respect of the H2 Facilities.

Transportation issues

Medium of transportation

A threshold issue for a hydrogen export project will be selecting a medium for transporting the hydrogen. Hydrogen may be transported in several different forms, and many carriers have been proposed. These range from gases (hydrogen itself, or nitrogen) to liquids (such as ammonia or MCH) and even solids such as metal hydrides or borane compounds.

Each carrier has a number of considerations to take into account including costs, safety and technical feasibility. There are different advantages and disadvantages associated with each carrier and despite significant recent technological progress, it remains unclear which and how many of these will become widely adopted for international maritime transportation.

Shipping terms and availability

In our hypothetical project, the hydrogen product would be exported internationally on a maritime vessel. Assuming the H2 SPA is on ex-ship terms, H2Co would be responsible for arranging the transportation and would likely need to have long-term arrangements (such as a long-term time charter party) to lock in the availability and pricing of transportation.

Where new technology is involved, project sponsors and lenders can be expected to conduct heightened technical and commercial due diligence on the vessel being used and its owner and operator.

If the H2 SPA is on 'free on board' (FOB) terms, the Offtaker will be responsible for arranging transportation. Particularly where there is a limited supply of vessels available for transporting hydrogen in the relevant form, or where the Offtaker desires long-term certainty of its transportation costs, the Offtaker may similarly see a need to have a long-term time charter or other long-term transportation arrangement in place.

Project financing

Given the scale of investment likely to be necessary for the development of our hypothetical project, we have assumed that the sponsors will seek project financing from a syndicate of international lenders. Furthermore, with many countries placing strategic importance on the development of the hydrogen supply chain, it is likely that ECAs will be among the financiers.

This financing would be limited-recourse and highly dependent on several 'bankability' factors including:

- completion risk, particularly given that relatively new technology will likely be involved (at least in terms of scale). A completion guarantee or debt service undertaking is likely to be required, at least with respect to early, large-scale projects. As a point of reference, whereas these forms of sponsor support to completion are not generally required for renewables projects, they continue to be required in respect of limited recourse financing of LNG liquefaction projects (with some exceptions, for example, in respect of US expansion projects);

- the level of "project-on-project" risk inherent in the separate construction of the renewables and hydrogen projects;

- long-term security of offtake, in the form of an H2 SPA with a creditworthy buyer willing to commit to purchasing the hydrogen product at a premium price for several years. This is discussed further below;

- reliability of operations, including having a reliable entity operating the Renewables Facilities and the H2 Facilities, as well as a reliable supply of water;

- a regulatory framework sufficiently mature and stable for the purposes of hydrogen project developments, in both the source and destination jurisdictions (see also our Global Hydrogen Guide). Ideally, there should be broad political support for hydrogen projects that will persist for the full project life-cycle and beyond;

- a robust security package giving lenders the ability to 'step in' and take on the obligations of the developer in certain circumstances, including assignment of equity interests in the borrower, and assignment of project agreements (including the sale and purchase agreements);

- appropriate quiet enjoyment and non-disturbance arrangements between H2Co, RenewablesCo and the lenders;

- in the event RenewablesCo and H2Co are financed separately, long-term security of power offtake by H2Co under a power purchase agreement, with appropriate credit support arrangements given that H2Co will be a special purpose company; and

- in the event RenewablesCo and H2Co are financed separately, the establishment of appropriate intercreditor arrangements.

Power supply and water supply

Under the 'split model' outlined above, H2Co will need to enter into a power purchase agreement (PPA) with RenewablesCo in order to secure a reliable supply of electricity to be used for hydrogen production via electrolysis. In the event that RenewablesCo is owned and/or financed separately from H2Co, RenewablesCo will likely require a parent company guarantee or alternative credit support to guarantee H2Co's payment obligations under that PPA.

The other input required for the production of hydrogen via electrolysis is water. Similar to the need for a PPA, appropriate long-term supply arrangements will need to be entered into by H2Co for water (an essential production input). Depending on the circumstances of the project, this may take the form of a typical sale and purchase agreement. However, if it is proposed that seawater will be used as a feedstock (for example, where the H2 Facilities are on a coast), the arrangements may be in a different form, such as licensing agreements and/or the attainment of relevant environmental approvals. Desalination may or may not be a required step in this supply chain, but this is likely to be dependent on technological developments and, in any event, is beyond the scope of this article.

Offtake agreement

One of the most crucial considerations for prospective financiers in our hypothetical project is security of offtake. To achieve this security, H2Co would most likely need to enter into one or more long-term H2 SPAs, with creditworthy Offtakers, at pricing terms and quantities considered sufficient to make the project economically viable and capable of repaying the debt. H2Co would give its lenders a security assignment over the H2 SPAs as part of the overall security package for the financing.

In addition to Offtaker creditworthiness, contract duration, pricing and quantities, a further key bankability concern will be the remedy available to H2Co under the H2 SPA if the Offtaker does not take the full contracted quantities of the hydrogen product. Until the cost of producing green hydrogen can be reduced through technological advancement and other developments, this price is likely to be significantly higher than the price of competing forms of energy. Furthermore, it is not clear how quickly a deep international market for green hydrogen will develop. Thus, if the Offtaker under the H2 SPA fails to take the green hydrogen product, there would be no guarantee that H2Co would be able to protect its cash flow by selling the hydrogen product to a different buyer at the same premium price.

Accordingly, the sale and purchase agreement would likely need to be a "take or pay" agreement under which the liability of the Offtaker for failing to take agreed quantities of hydrogen product would be payment of 100% of the contract price. The agreement may include a mechanism for the Offtaker, after having paid "take or pay", to later receive additional "make up" hydrogen product (if available from the project), or to receive the "net proceeds" of any replacement sale that H2Co is able to make in respect of the quantity the Offtaker failed to take. Whether a "make-up" or "net proceeds" mechanism is adopted may depend on how quickly the parties think that there will be relatively robust short-term trading of green hydrogen. By analogy, early LNG sale and purchase agreements tended to adopt a make-up mechanism but, as the spot LNG market has developed, there has been a shift to a "net proceeds" mechanism.

A possible alternative to the sale and purchase arrangements outlined above would be a tolling model similar to that seen in some LNG projects. Here, a long-term, creditworthy tolling customer would supply the inputs required to produce hydrogen and pay a "tolling fee" to H2Co to produce it. In this case, the tolling customer would pay for and supply to H2Co the electricity (and possibly the water) required to produce green hydrogen using H2Co's electrolyser. H2Co would produce, convert, and store the hydrogen product at H2Co's facilities and then load the hydrogen product onto vessels provided by the tolling customer, in exchange for such customer paying a monthly fee to H2Co for the tolling capacity and services.

Such a tolling arrangement would shift certain risks (such as power supply) from H2Co to the long-term customer and would likely only be attractive (as compared to an H2 SPA arrangement) if the overall cost to the customer is sufficiently lower and/or there are additional considerations at play, such as the customer owning a significant equity interest in the project.

Local supply

Our hypothetical project is premised on the notion that the project would be in a location with an abundance of "stranded", or at least excess, renewables resources such that it would make more economic sense to use the energy produced by RenewablesCo to make hydrogen than to supply the local grid. The project would essentially be repackaging renewable power produced at such a location for transportation in the form of hydrogen product to demand centers in other countries.

Nevertheless, to the extent there is local demand for additional electricity, RenewablesCo might build renewable capacity in excess of what is required for hydrogen production. RenewablesCo could then connect to the local grid and sell some electricity into the local market and improve project economics. An additional benefit could be that this would allow sales of power partially to mitigate revenue lost where, for example, the H2 Facilities are down for unplanned maintenance or due to force majeure but the Renewables Facilities remain operational.

Similarly, to the extent that there is a local hydrogen market (for example, to fuel long-haul fuel cell trucks or for use in industrial processes) there might be additional benefits in selling some quantities for use in the local market.

If local sales capability is intended for the project, it can be expected that financiers will want to ensure that project agreements appropriately address the allocation of renewable power and hydrogen product between what is required to satisfy obligations under the H2 SPA and what is available for sales into the local market, particularly in cases where energy or hydrogen production is curtailed due to force majeure or unplanned maintenance.

Subsidies and regulatory incentives

Another key consideration is the impact of policy initiatives and regulatory frameworks, in both the source and destination countries.

Subsidies toward the cost of building hydrogen facilities could help reduce capital costs and thereby decrease the amount of premium that needs to be charged for the green hydrogen in order for the project to be commercial and bankable. However, as green hydrogen can be several times more expensive than competing fuels, such as LNG, it is likely that ongoing incentives will be needed to help the Offtaker defray the relatively higher cost of using green hydrogen.

Therefore, to the extent that there is a carbon tax on such competing forms of energy but not on green hydrogen, this could help hydrogen's competiveness to some degree. In addition, a system similar to renewable energy certificates (RECs), but based on the downstream power produced from green hydrogen (rather than the upstream power produced by RenewablesCo) could help unlock the value of green hydrogen and partially offset such higher cost. Provided the hydrogen economy scales up and matures, substantial cost reductions will be achieved. Until such time, it is likely that additional on-going incentives, such as feed in tariffs, feed in premiums or contracts for difference will be needed in order to entice potential offtakers to commit to long-term purchases of green hydrogen at prices sufficient to make the hydrogen project commercially viable and bankable.

As the world is in a period of transition toward lower carbon economies, it may be uncertain whether any incentives in place at the time the project is undertaken will remain in place in the same form for the entire duration of the financing and long-term H2 SPAs. Accordingly, the relevant agreements will need to address the allocation of risk of changes in regulatory incentives and to do so in a way that protects RenewablesCo's and H2Co's ability to repay their financing.

*******************

The example discussed in this article is entirely hypothetical in nature and is not based on any past, current or proposed project developments. We have drawn from our deep experience advising on market-defining renewables, LNG and other projects in Asia-Pacific and our current involvement on several emerging hydrogen initiatives to formulate this case study.

References

White & Case means the international legal practice comprising White & Case LLP, a New York State registered limited liability partnership, White & Case LLP, a limited liability partnership incorporated under English law and all other affiliated partnerships, companies and entities.

This article is prepared for the general information of interested persons. It is not, and does not attempt to be, comprehensive in nature. Due to the general nature of its content, it should not be regarded as legal advice.

© 2021 White & Case LLP