While Vietnamese LNG-to-power projects dominate the headlines, developments across the Mekong river delta in Cambodia may soon seize the spotlight.

In January 2020, a Cambodian entity, the Cambodian Natural Gas Corporation (CNGC), welcomed its first LNG imports from China National Offshore Oil Corporation, marking the commencement of CNGC's 15-year plan to develop the country's LNG infrastructure as part of its policy to reduce its dependence on hydropower and coal. Coupled with Cambodia's surging demand for power and relatively creditworthy national utility company, these plans justify cautious optimism for the future of the country's LNG-to-power sector. This article discusses the basis for this optimism, as well as the legal and technical challenges facing the sector.

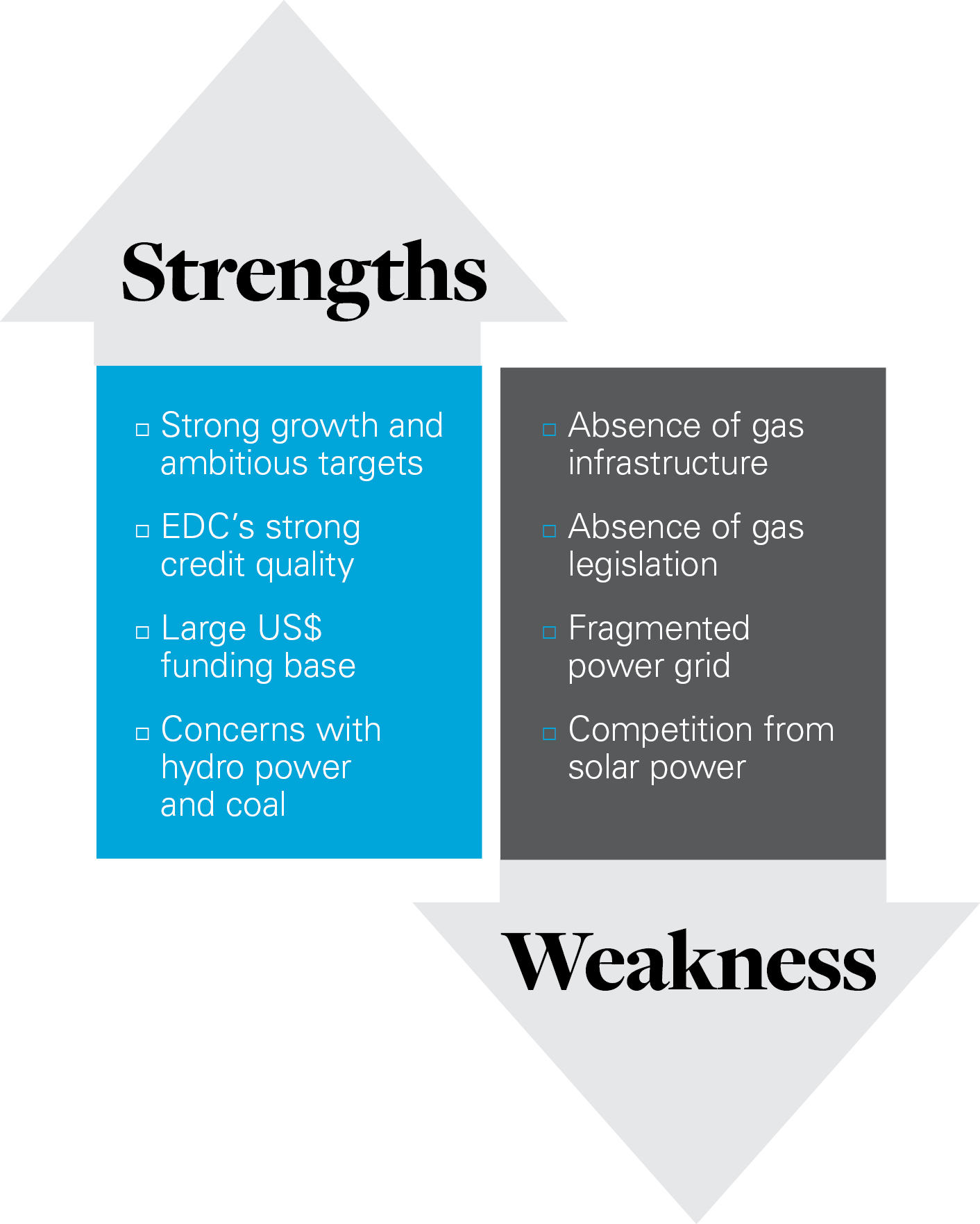

Strengths of Cambodian power sector

- Rapid economic growth and ambitious power development targets - Experiencing rapid economic growth and urbanisation, Cambodia's demand for electricity is surging. The country has the lowest electrification rates among the ASEAN countries after Myanmar, and the Cambodian government has recognised the importance of developing the domestic power sector to sustain the pace of the country's economic upswing, targeting grid-quality electricity access for at least 70% of households by 2030. Fitch Solutions forecasts net power consumption increasing from about 10.4TWh in 2019 to 13.2 TWh by 2024. Together with the Cambodian government's objective of achieving greater energy self-sufficiency following years of reliance on energy imports, this rising need for power is expected to fuel demand for domestic electricity generation.

-

Relatively strong credit quality of the national utility offtaker - Given the traditionally high retail electricity tariffs in Cambodia, the national utility company, Electricite du Cambodge (EDC), is profitable and does not rely on financial support from the government to purchase electricity from private-sector power generators. In 2019, it recorded revenues of 6.5trn Cambodian riel (CR), approximately US$1.6bn, and a net profit of CR661.7bn (about US$162m). Its net profit has more than tripled since 2012.

There are signs of emergent headwinds that may adversely affect EDC's credit quality. The government implemented an electricity tariff reduction plan in 2015, which reduced tariffs for select customers. EDC's costs are expected to increase with the commissioning of new major power projects and a planned expansion of the EDC network. That said, EDC remains robust from a credit perspective relative to its counterparts in the region.

- FX risks mitigated by dollarised economy and relatively large US dollar base of reserves - The Cambodian government is reported to have a comparatively large base of US dollar reserves. Cambodia closely pegs the riel to the US dollar, and permits without restrictions US dollar in-flows into the country and the performance of transactions with US dollars (including the issuance of US dollar-denominated credit). The Law on the Foreign Exchange of 1997 does not restrict foreign exchange transactions. The confluence of these factors contributes to the reported dominance of the US dollar in Cambodia, with economists estimating that 90% of the economy is dollarised. This mitigates foreign currency risks inherent in US dollar- denominated investments into local currency revenue-generating projects.

-

Concerns with hydropower and coal, creating space for alternative sources of baseload power - Coal and hydropower are the primary sources of power in Cambodia, but concerns with these sources are mounting. Coal power's carbon footprint and its rapidly diminishing access to international bank and capital market financing have increased the developmental and political costs of such projects. In 2020, several major global brands, including H&M, Adidas, Puma and Nike, lobbied the Economy Minister to curtail the country's coal expansion plans.

Issues with hydropower are widely known. Hydropower dams and reservoirs often have an adverse ecological and social impact, putting pressure on endemic fish species and other fauna, and forcing the resettlement of surrounding communities. Hydropower plants in the Mekong region are subject to the mercy of the rainy season; severe droughts in 2019 dried up the country's hydropower dams, resulting in nation-wide power shortages. As a result, the Cambodian government announced in 2020 a moratorium on the development of hydropower projects on the mainstream Mekong for the next decade. Fitch Solutions has predicted that the share of hydropower generation will drop 15 percentage points over the next decade (from around 45% in 2019 to 30% in 2029).

In light of these concerns with Cambodia's traditional sources of base load power, there is likely to be space for LNG-to-power projects. At a recent inter-governmental energy forum, the Ministry of Mines and Energy (the MME) outlined its vision that LNG and natural gas will comprise important components of Cambodia's power mix in the near future, and its plan for up to 3,600 MW of gas-fired power plants by 2030.

Possible hurdles to development

-

Absence of gas infrastructure - With no known gas reserves and modest natural gas consumption, the gas infrastructure in Cambodia is unsurprisingly underdeveloped. The country has no LNG receiving terminals, long-distance pipeline networks, urban gas supply facilities, regasification stations or other natural gas infrastructure. Given the absence of this gas transmission network, LNG-to-power projects will have to rely on their own regasification and gas transportation facilities, probably limiting commercially viable projects to coastal schemes that do not require extensive pipelines from LNG receiving terminals.

However, as noted above, CNGC has a 15-year plan to build out the gas infrastructure. As part of this plan, it intends to develop an LNG receiving terminal, 27 urban LNG multi-function stations, a fleet of LNG trucks and 2,825km of inter-provincial high-pressure pipelines. Medium and low-pressure pipeline networks and point-to-point regasification stations in the cities are also being considered.

- Absence of clear gas legislation - The regulatory framework governing the oil and gas sector remains insufficiently developed in Cambodia. In July 2019, the government enacted the Law on Management of Petroleum and Petroleum Products. Although this law purports to govern domestic oil and gas activities, it lacks clarity and specificity, including on the rules governing the importation of LNG, the regasification of LNG to natural gas and the transportation of natural gas within Cambodia. Investors are likely to require greater regulatory certainty on these key issues before being comfortable investing in the country's LNG-to-power sector.

- Fragmented power grid - Cambodia's power grid requires major capital upgrades to provide stable and reliable electricity to major population centres. The grid is fragmented and near full capacity. In its current state, it will almost certainly have difficulty sustaining the additional load from customarily large LNG-to-power projects. This may change in the medium-term future. In a report released for 2019, the MME and the Electricity Authority of Cambodia (the EAC) outlined a plan to upgrade the national grid by 2023. The Asian Development Bank is supporting EDC in a grid reinforcement project to improve transmission network capacity and stability through the provision of loans and grants.

- Competition from solar power - Solar power is likely to be LNG-to-power's biggest rival, given falling costs of solar technology, the ability to scale up in solar projects and strong solar irradiance in Cambodia (one of the highest in the Mekong sub-region). The government is also seeking to increase investment in clean and renewable energy, especially in solar power, as enunciated in the National Strategic Development Plan for 2019-2023. The first solar auction conducted by EDC for a 60MW solar park garnered lots of investor interest and yielded the lowest electricity price in South-East Asia (as announced by the Asian Development Bank in September 2019).

Gazing into the crystal ball

Cambodia's potential is starting to attract international attention. With long-standing Cambodian-Chinese ties and trade between the two countries reaching US$9bn in 2018, Chinese interest in Cambodia is increasing, with Cambodia signing its first bilateral trade agreement with China in October 2020. Chinese investment in the power industry includes the 700MW coal-fired power project in Sihanoukville and the 150MW hydropower plant in the Thma Bang district.

Japanese investors have also begun to scour Cambodia for investment opportunities. Two Japanese firms, Aura Green Energy Co. and WWB Corp, teamed up in 2020 to build a biomass plant, partly subsidised by the Japanese government. In a meeting with the MME in November 2020, the Ambassador of Japan to Cambodia noted that Japanese firms are considering investing in a waste-to-energy plant and LNG storage stations in Cambodia.

While major upgrades to Cambodia's physical and legal infrastructure are required to incentivise investment in domestic LNG-to-power projects, the fundamentals are encouraging and lifted by political tailwinds supporting alternative baseload capacity. Investors wishing to participate in the region's undeniable growth story should keep watchful eyes on LNG-to-power opportunities in the heart of the former Khmer empire.

FIGURE 1 - STRENGTHS AND WEAKNESSES

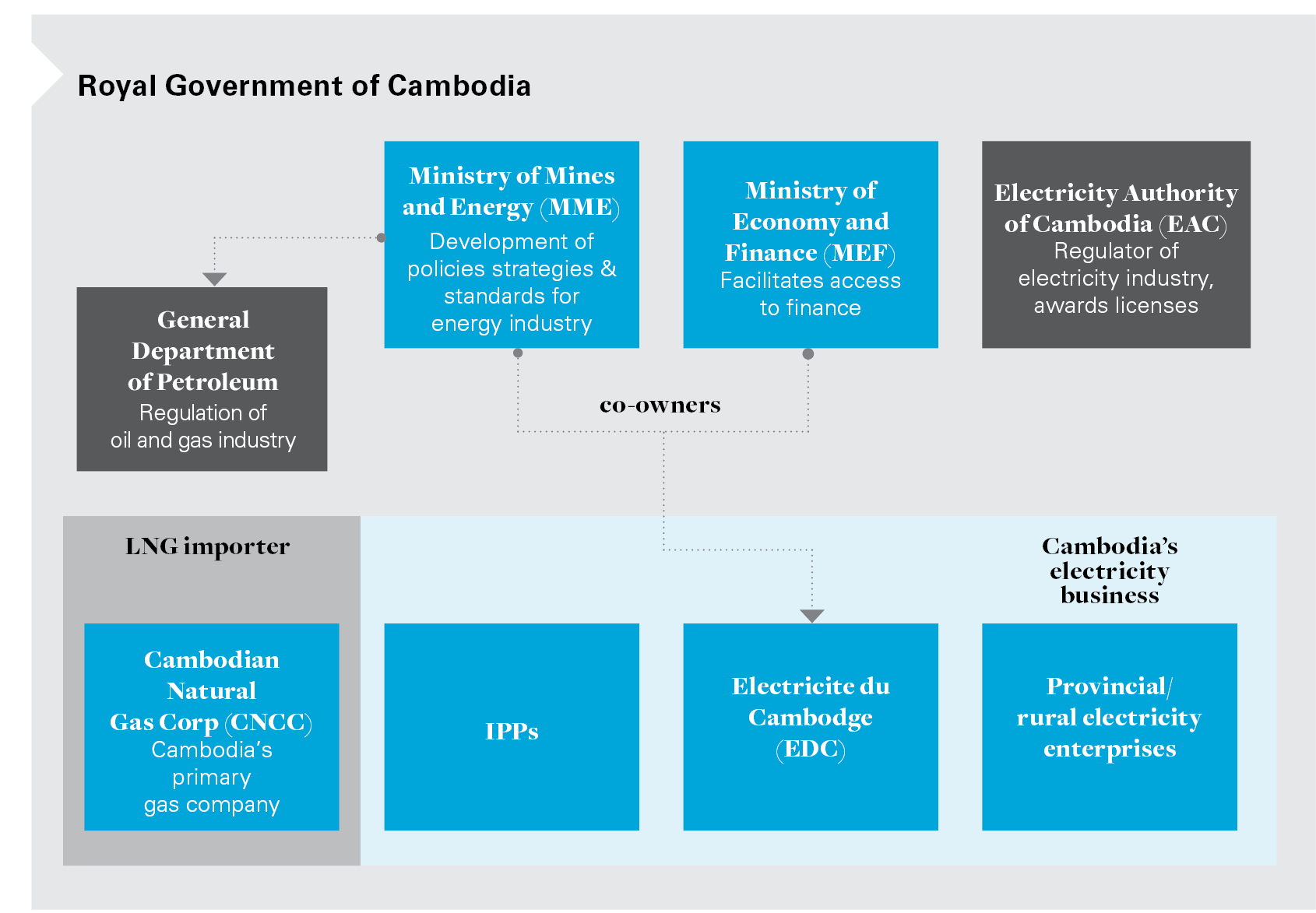

FIGURE 2 - THE GOVERNMENT

TABLE 1-KEY GOVERNMENT ACTORS

|

Key government players |

Functions |

|---|---|

|

CNGC |

CNGC is Cambodia's primary gas company. In 2019, CNGC was granted a licence to import LNG (currently the only buyer in Cambodia with an LNG import licence), and had plans to import up to 35,000 metric tons (mt) of gas in 2019, and 100,000 mt in 2020. |

| EAC |

The EAC is an autonomous governmental agency with the authority to enact regulations on power market operations, to award electricity licences and to set and review tariff levels. All electricity generation, supply and distribution have to be licensed by the EAC. |

|

EDC (Cambodia's national electricity utility) |

EDC is responsible for generation, transmission and distribution of electricity to areas assigned to it by the EAC, with most of its electricity sold in Phnom Penh and 12 provincial towns. EDC's mandate includes extending and integrating the local grids of private energy producers with the national grid, and facilitating rural electrification in regions where private-sector rural electricity enterprises supply these rural areas with off-grid electricity. |

|

General Department of Petroleum |

The General Department of Petroleum, part of the MME, is responsible for regulating the oil and natural gas industry, and the sales of petroleum products. |

|

MEF |

MEF The MEF plays a central role in securing international financial assistance for the country and in managing and servicing foreign credit. It also facilitates EDC's access to finance. |

|

MME |

MME The MME is responsible for the development of government policies, strategies and standards for the energy industry. Together with the MEF, it owns EDC. |

Summary of key government players

The key governmental actors in the Cambodian power and gas sector are the Ministry of Mines and Energy (MME), the Ministry of Economy & Finance (MEF), Electricite du Cambodge (EDC), the Electricity Authority of Cambodia (EAC) and CNGC.

This post was first published on Project Finance International.

White & Case means the international legal practice comprising White & Case LLP, a New York State registered limited liability partnership, White & Case LLP, a limited liability partnership incorporated under English law and all other affiliated partnerships, companies and entities.

This article is prepared for the general information of interested persons. It is not, and does not attempt to be, comprehensive in nature. Due to the general nature of its content, it should not be regarded as legal advice.

© 2021 White & Case LLP