United Kingdom

There have been several interesting developments in merger control in the UK over the past year, including the official separation of the UK from the EU merger control regime and the proposal of a new national security regime that will see notification for certain transactions become mandatory in the UK for the first time.

21 min read

Subscribe

Stay current on your favorite topics

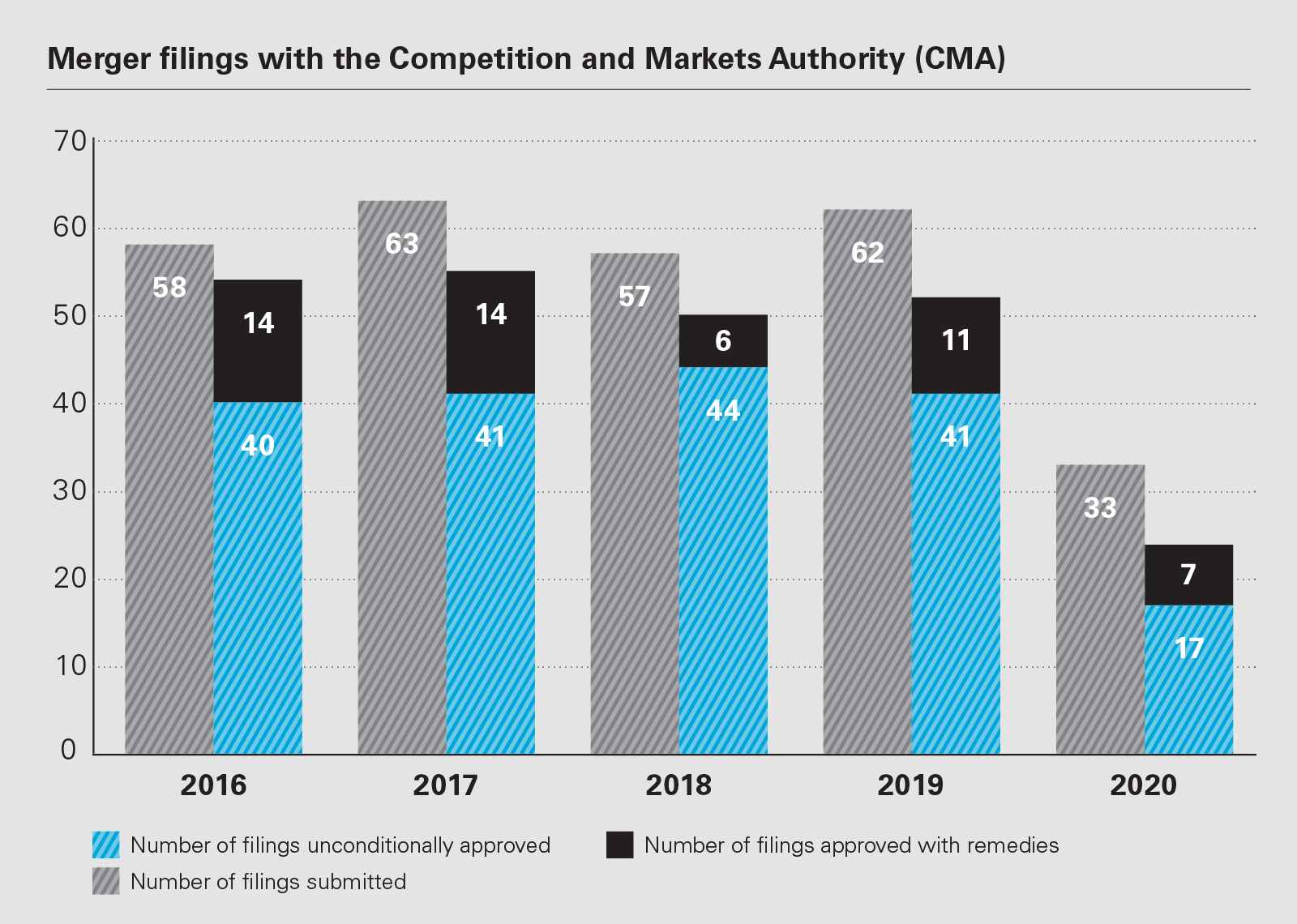

62

merger filings were submitted to the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) in the year to April 2020. This compares to 57 in the year to April 2019

41

Merger filings were approved – conditionally or unconditionally - by the CMA in the year to April 2020. This compares to 44 in the year to April 2019. 7 mergers were blocked or abandoned in the year to April 2020, compared to 5 in the previous year, which suggests a harsher enforcement climate (although this is denied by the CMA).

Key developments

There have been several interesting developments in merger control in the UK over the past year. These developments include cases where the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) has investigated mergers in cases that appear, at least on one level, to have limited connection to the UK.

There has also been greater enforcement of procedural matters such as alleged breaches of interim enforcement orders, colloquially known as "hold separate" orders.

A major development in merger control in the UK in 2020 was the expansion of the list of sectors in which the UK government can intervene on public interest grounds.

If jurisdictional tests set out in the Enterprise Act 2002 are satisfied, the government can intervene so that the merger is reviewed on public interest grounds, as well as on competition grounds.

Over the past year, as a result of the coronavirus pandemic, the range of public interest considerations (PICs) has been extended from the three PICs previously specified, which were national security, plurality of the media and stability of the financial system.

The Enterprise Act allows the government to specify additional PICs. In the same way that stability of the financial system was added as a PIC after the global financial crisis, the coronavirus pandemic has led the government to include another PIC, specified as "the need to maintain in the UK the capability to combat, and to mitigate the effects of, public health emergencies".

Changes culminated in November with the publication of the new National Security and Investment Bill (NSIB), which will create a stand-alone investment review regime for national security cases, completely divorced from competition law in the UK for the first time.

The other cases in which a PIC may be relevant—media plurality, financial stability and public health emergencies—will not change, and are linked to the Enterprise Act merger regime.

The NSIB, on the other hand, will be a separate regime, operating alongside the merger control regime. It will require mandatory notification for certain deals involving the acquisition of shares and/or voting rights in companies active in 17 designated sensitive sectors, including defense, energy, transport and artificial intelligence.

The regime will see such deals reviewed for potential national security concerns, with the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (SoS) empowered to impose conditions on transactions, and potentially unwind or block them where sufficient national security concerns are unearthed. The new regime takes obvious inspiration from its US cousin, the Committee on Foreign Investment, although is arguably broader in certain aspects in that, as currently drafted, it will apply to all investors—not just those from outside the UK.

The scope of target companies that will fall within its auspices is also very broad as it is expected to apply to all companies in the sensitive sectors with sales in the UK, whether or not they are UK-registered or have an active presence in the country.

Of particular note is the retrospective power to review deals that have already been concluded. This means that although the NSIB has not yet entered into force, once it does, deals closed from 12 November 2020 will fall within its scope. In addition, once enacted, the law will allow the SoS to review deals that were not notified up to five years following completion. The UK Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy ran a consultation on the scope of the sensitive sectors that will be subject to mandatory notification, which closed on 6 January 2021. In the meantime, the NSIB is making its way through parliament with adoption expected in the first half of 2021.

This interventionist approach is also evident in general merger control practice. For example, in Roche's acquisition of US gene therapy company Spark Therapeutics, the CMA was able to find that the share of supply test was satisfied, in spite of Spark having no UK sales. The CMA justified its finding on two grounds, based on the 'share of supply' test under the Enterprise Act. Firstly, the "number of UK-based employees" engaged in activities relating to hemophilia A treatments, and, secondly, the number of UK patents procured by the merging parties for these treatments.

Similarly, in connection with Amazon's acquisition of a 16% stake in Deliveroo, the CMA asserted jurisdiction on the basis that the minority stake gave Amazon 'material influence' over Deliveroo, and conducted an in-depth review of the deal even though Amazon had exited the restaurant delivery market in the UK.

While both deals were ultimately found not to give rise to competition problems in the UK and were cleared accordingly, there are various cases from the past year in which the CMA's concerns resulted in a transaction being blocked.

In blocking the merger between Sabre and Farelogix, both of which supplied software solutions to help airlines sell flights via travel agents, the CMA found that the share of supply test was satisfied on the basis of revenue in the supply of IT solutions to UK airlines, even though Farelogix had an (indirect) agreement with only one UK airline.

The decision to block the deal came after the US District Court of Delaware had recently cleared it, ruling against the US Department of Justice, which had challenged the merger.

Another development in the past year has been the CMA's consideration of the effects of the coronavirus pandemic in reaching its decisions. The CMA has given careful consideration to the impact of the pandemic on the merging parties and competition in the relevant markets more generally. However, in no case has the CMA found that the impact of the pandemic was sufficient reason to clear a problematic merger, notwithstanding the severe adverse impact it has had on the target company. For example, the CMA blocked the acquisitions of Footasylum by JD Sports, and StubHub by viagogo, even though the pandemic has materially impacted on their businesses. In the Amazon/Deliveroo case, the CMA initially found that the pandemic would lead to Deliveroo going out of business but subsequently reversed that finding and ultimately concluded that the transaction would not harm competition.

£1 million

The UK government can invoke public interest considerations (PIC) to intervene in mergers in certain sectors if the UK turnover of the target is more than £1 million. These cases will fall under the new NSIB regime once it comes into force.

Impact on merging parties

As has been the case for some time, internal documentary evidence has played an important role in the CMA's competitive analysis. However, the extent of requests for internal documents, including emails, has steadily increased even in Phase I investigations.

Relevant internal documents are typically those produced to inform business strategies, investment decisions and for general planning purposes. In the Sabre/Farelogix deal, internal documents provided an important insight into the parties' ability to compete, their perception of competitive threats and how this affected their strategic thinking. The documents were then used to support the CMA's theories of harm.

Similarly, the CMA examined a large number of internal documents in its investigation of Amazon's minority investment in Deliveroo. It focused particularly on the likelihood of Amazon re-entering the online restaurant delivery market; whether Deliveroo may have started to deliver more non-food items in competition with Amazon; and what future competition between the parties might look like.

These decisions show that the CMA views internal documents as a reliable way of gauging parties' intentions, both in the past and the future. Companies looking at potential mergers should put emphasis on document management, both in terms of information memoranda and other market-facing materials, but also with respect to internal communications, some of which will pre-date any merger plans.

It is good discipline to ensure that all documents and emails are considered potentially disclosable in future merger reviews and to draft clearly and unambiguously.

While economic evidence has always played an important role when assessing the likelihood and potential effect of competition issues in mergers, developments over the past few years suggest that greater account may be taken of merging parties' arguments on efficiencies. Nonetheless, it remains very difficult to convince the CMA that efficiencies are likely to outweigh any potential adverse impact on competition that it may have identified.

Although, post-Brexit, the CMA is no longer bound by rulings of the European Courts, their judgements may still be important. In a decision of the General Court in May 2020, its criticism of the European Commission for failing to take efficiencies analysis into account in its assessment of the merger between telecoms companies Three and O2, suggests that an increasing focus on efficiencies may be beneficial in complex cases—both when dealing with the European Commission and with the CMA.

Internal documentary evidence has played an important role in the CMA’s competitive analysis for some time now, and it's good discipline to ensure that all documents and emails are considered potentially disclosable

The impact of COVID-19

Despite the global disruption caused by COVID-19, the CMA made it clear from the outset that there would be limited impact on its merger control operations.

In guidance released in April, the CMA set out some expected changes to its procedures. It said there would be a likely delay in certain aspects of investigations, particularly at the pre-notification stage; no imposition of penalties where businesses were unable to comply with requests for information as a result of the pandemic; and that all meetings—including hearings and site visits—would take place remotely.

However, no changes of substance were made. Notifications were still accepted, statutory deadlines for the CMAs work were unaffected, and there was no loosening of the standards applied.

In fact, the CMA, anticipating the likely deluge of "failing firm" defense claims, published specific guidance on this issue. This confirmed that the failing firm defense would only be accepted in exceptional circumstances, pandemic or no pandemic.

In the Amazon/Deliveroo case, the CMAs provisional findings, published at the height of the pandemic, found that Deliveroo would fail if it did not get the investment from Amazon, but subsequent evidence led the CMA to reverse its findings in the failing firm defense when it later cleared the transaction.

In practice, the pandemic has had little impact on the merger clearance process, both procedurally and substantively.

December 8, 2020

The CMA published the DMT's advice to Government

Recent changes in priorities

The publication of the new NSIB makes clear that national security is a top priority for government review. Numerous cases from the past year under the existing regime bear this out, including Inmarsat/Connect Bidco, Cobham/Advent and Mettis/Aerostar, all saw the SoS issuing a public interest intervention notice on national security grounds. These interventions tended, historically, to be made in the context of defense-related transactions, but now are being made in a wider set of circumstances.

This is further exemplified by the expanded list of sectors contemplated for inclusion in the new NSIB, including energy, transport, communications and artificial intelligence. Outside the investment review proposals, it is evident that the UK government is increasingly concerned with mergers in the technological and cyber spheres.

In addition, in May 2019, it commissioned an assessment to review previous decisions taken in the context of digital mergers, assess whether they were reasonable, and evaluate whether cleared mergers led to a deterioration in market conditions.

The review recommended actions such as the increased use of dawn raids in merger investigations to help predict the evolution of a business, something which is inherently tricky in the fast-moving technology world.

It also showed a greater willingness to accept uncertainty in counterfactuals, and a greater willingness to "test the boundaries of the legal tests and constraints" that regulators face.

In June 2019, the CMA then launched a call for information on digital mergers to help it update the Merger Assessment Guidelines in the context of digital markets. The consultation focused on issues such as the relevant market features for assessing mergers in digital markets; how these features might impact the possible theories of harm; and the evidential weight that should be attached to internal documents indicating that the purpose of the transaction is to eliminate a competitive threat or a high transaction value relative to the market value or turnover of the target.

The results of the consultation are still pending at the time of writing. While concerns have been raised that some deals may be "killer acquisitions," the CMA has approved mergers after considering such concerns, such as Visa's acquisition of fintech network Plaid.

In that case, while the CMA found that Plaid would have been an increasing competitive threat to Visa in the future, sufficient competition would continue to exist post-merger from other suppliers and other types of services enabling consumer-to-business payments. The merger was ultimately abandoned when challenged by the Department of Justice in the US.

Digital markets more generally continue to be a focus point for the CMA. Following the publication of its market study report on online platforms and digital advertising in July 2020, in December 2020 the CMA published the advice produced by its Digital Markets Taskforce (DMT) to the Government on the design and implementation of the UK's new pro-competition regime for digital markets. The so called 'Strategic Market Status (SMS) regime' will apply to "the most powerful tech firms with substantial, entrenched market power where the effects of that market power are particularly widespread or significant. Overseeing the proposed SMS regime would be a specialist Digital Markets Unit (DMU) which would function as a "centre of expertise and knowledge" and a pro-active enforcer of digital markets. As far as next steps are concerned, the Government has committed to establish the DMU within the CMA from April 2021 and to consult on these proposals for a new pro-competition regime and legislate to put the DMU on a statutory footing when parliamentary time allows.

Key enforcement trends

Greater CMA scrutiny is certainly a notable trend, with the CMAs annual plan for 2020/21 noting an "unprecedented number" of Phase II merger investigations.

The CMA has not been shy about asserting its competence to review mergers that might appear, at first blush, to fall outside its jurisdiction—including both Roche/Spark and Sabre/ Farelogix. In both cases, the target parties had minimal UK presence (and limited, if any, turnover in the UK), but the CMA asserted jurisdiction on the basis of the share of supply test, using frames of reference that the parties considered to be highly questionable.

This approach has led, in part, to an uptick in challenges to CMA merger decisions. For example, Sabre is challenging the CMA's prohibition decision, even though Farelogix has now been sold to another party. JD Sports is also challenged the CMAs decision that found that the completed acquisition of a rival, Footasylum, was anti-competitive and required the divestment of the Footasylum business, with the Competition Appeals Tribunal (CAT) remitting the case back to the CMA in December 2020 for reconsideration (the CMA applied for permission to appeal the CAT's judgement but the CAT denied this; on the 17 December 2020 the CMA renewed its application for appeal at the Court of Appeal—the case is ongoing). In another case, the CMA prohibited FNZ's acquisition of GBST, which it is now reviewing again after acknowledging some mistakes in the way market shares had been calculated—although it may still conclude again the merger ought to be prohibited.

There is no doubt that the impact of COVID-19 will also increasingly feature in merger review cases going forward. In both Sabre/Farelogix and JD Sports/ Footasylum, the CMA acknowledged the impact of coronavirus on the parties' businesses, but ultimately found that the impact of the pandemic did not mitigate competitive concerns.

However, the pandemic did prompt the CMA to allow JD Sports additional time to sell Footasylum.

Likewise, in Amazon/Deliveroo the CMA's provisional findings indicated a willingness to accept that Deliveroo could potentially be facing a market exit due to the impact on its liquidity position caused by COVID-19. Ultimately, however, the CMA concluded that Deliveroo had managed to reverse its fortunes and the deal was cleared on the ground that it was not expected to result in a substantial reduction of competition.

2000

UK government estimates that there will be almost 2000 cases per year scrutinized under the National Security and Investment Bill (NSIB), with around 10 of these expected to result in some form of remedy

Recent studies and guidelines

The CMA's April 2020 guidance on merger assessments during the coronavirus pandemic confirmed that the CMA would not be changing the way it undertakes merger control assessments or any merger control deadlines, despite the outbreak. The guidance made clear that the CMA would be seeking to operate on a "business as usual" basis for merger control purposes.

The CMA also published supplemental guidance on the use of the failing firm defense, in anticipation of an increase in mergers involving failing firm claims. The guidance made it clear that there would be no change to the application of the defense, but noted that events that occur during the CMAs review of a transaction—including the impact of the outbreak on a firm's operations—can be incorporated into the assessment of competitive effects for merger control purposes.

In addition, the government published guidance following changes to the turnover and share of supply tests for the purposes of intervening in mergers in certain sectors. The guidance explains why the government amended the Enterprise Act, describes the legal and practical effects of the amendments, and offers advice to businesses and others about how they may be affected by the changes. Following this, the CMA published an update to its Merger Assessment Guidelines which explain the substantive approach of the regulator to its analysis when investigating mergers. The CMA notes that since the current guidelines were published (in 2010) markets have evolved and changed at a rapid pace. The central focus of that evolution appears to be on digitalisation with the CMA writing that the guidelines build on recommendations made by the Furman and Lear reports in 2019 on how the CMA should approach its assessment of digital mergers.

The CMA writes that these changes have not introduced new theories of harm or economic principles in the field of merger control but they do suggest some development of them, for example, in expanding the section on "loss of future competition" (a theme particularly relevant in digital markets in relation to so called "Killer Acquisitions"). The consultation on the updated guidelines closed in January 2021 and are expected to be published shortly.

Looking ahead

The new NSIB regime is expected to lead to the mandatory notifications of around 1,000 to 2,000 deals a year with a further 70 to 95 transactions expected to be called in for review. As the existing regime under the Enterprise Act sees, on average, fewer than one intervention a year, the government expects interventions to be a much more common feature of the merger landscape.

Trigger events that will require the parties to notify their transaction under the NSIB will include acquisitions that bring a party's share of equity or voting rights over various thresholds of 15 percent, 25 percent, 50 percent or 75 percent, as well as the acquisition of material influence—for example through increased board representation conferring material influence over the company.

Under the NSIB the government will assess all national security issues under the new regime, which will operate separately from, but alongside, the Enterprise Act. Currently, when the SoS believes that a PIC arises, he or she instructs the CMA to investigate. The CMA then reports to the government on competition issues and also summarizes representations on the public interest issue. Under the NSIB, the CMA would no longer have this role. However the CMA will continue to review mergers on competition grounds and also if the SoS intervenes in respect of other PICs under the Enterprise Act, namely financial stability and public health emergencies.

Other key changes in the proposed NSIB legislation includes the introduction of the ability for the SoS to intervene and review deals on national security grounds for up to five years, or—if the SoS is aware of the transaction— six months after they close. This compares to the CMAs ability to take action only up to four months post-completion under the Enterprise Act, a time limit that will continue to apply to the competition aspects of mergers even if the national security implications can be reviewed for up to five years post-closing.

Guidance from the government on the scope of the mandatory notification requirement under the NSIB regime will be welcome. In any event, it is clear that engagement with the government on cases in the designated sectors will be essential to ensure as smooth a regulatory process as possible.

The CMA will take on responsibility for merger cases that were previously reserved to the European Commission; typically, those are the larger and more complex cases. The CMA is ready for this challenge

The CMA will take on responsibility for merger cases that were previously reserved to the European Commission; typically, those are the larger and more complex cases. The CMA is ready for this challenge

Brexit

Following the end of the Brexit transition period on December 31,2020, UK turnover is no longer counted as EU turnover for the purposes of establishing which merger control authorities may have jurisdiction over the transaction. Consequently, some deals may now be notifiable in the UK as well as to the European Commission (or in certain EU Member States).

Since the conclusion of the Trade and Cooperation Agreement on Christmas Eve 2020, the UK is now the master of its own destiny when it comes to merger control. Deals that would previously have benefited from the EU 'one stop shop' may now require notification under EU merger control rules and merit separate CMA attention meaning deal makers may now be facing parallel review by both authorities.

This also means an increased workload for the CMA. The CMA expects that this expanded responsibility will increase its merger workload by between 40 percent and 50 percent, with an additional 30 to 50 Phase I investigations and approximately six additional Phase II investigations each year.

Notwithstanding the CMA's autonomy over these cases it is expected that it will continue to work closely with the EU, and EU Member States, when considering the impact on competition of mergers, and the design of potential remedies that may be necessary.

THE INSIDE TRACK

What should a prospective client consider when contemplating a complex, multi‑jurisdictional transaction?

For deals in potentially sensitive sectors such as cyber‑related or artificial intelligence, clients should consider the proliferation of global foreign direct investment rules, including the new NSIB regime in the UK, as well as greater scrutiny of such deals under merger control regulations.

Even deals that pre-date the entry into force of the NSIB will be capable of retrospective review so investors should consider now whether their transactions could have potential national security implications.

Finally, clients should continue to be careful with the content of internal documents.

In your experience, what makes a difference in obtaining clearance quickly?

Navigating a smooth path through merger control approvals depends on various factors. These include being prepared and, where possible, doing as much work as possible upfront so you are ready to respond to questions from authorities. It also helps to think early about potential remedies even if you are confident that they will not be needed. In addition, to the extent possible, engaging with customers early on to determine their likely reaction and to be able to react to any concerns they may have is also very worthwhile.

What merger control issues did you observe in the past year that surprised you?

The growing trend of the CMA to pursue procedural infringements, such as alleged breaches of "hold separate" orders or the provision of allegedly incomplete (or late) information in merger cases, has been notable. Even in cases that have been cleared, there is an increasing appetite to pursue companies for such alleged infringements.

While some cases appear clear-cut, others are more questionable. It is a wake-up call for both clients and advisers. On the other hand, the General Court judgment in Three/O2 about the standard of proof in oligopolistic markets is a welcome development that will have wide‑reaching implications.

White & Case means the international legal practice comprising White & Case LLP, a New York State registered limited liability partnership, White & Case LLP, a limited liability partnership incorporated under English law and all other affiliated partnerships, companies and entities.

This article is prepared for the general information of interested persons. It is not, and does not attempt to be, comprehensive in nature. Due to the general nature of its content, it should not be regarded as legal advice.

© 2021 White & Case LLP

View full image: Merger filings with the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) (PDF)

View full image: Merger filings with the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) (PDF)