The Financial Action Task Force ("FATF") is the global standard-setter on anti-money laundering ("AML"), countering terrorist financing ("CFT") and counter proliferation financing. FATF's standards, also referred to as "recommendations", are implemented by countries into their national legal frameworks. Countries which fall short of these standards, or standards set by other supra-national bodies, are placed on lists generically referred to as the "Black List" or the "Grey List." This article examines the economic effect on countries placed on these money laundering lists.

The Lists

FATF was created in 1989 by the G7 countries to lead the global effort to combat money laundering. The members of FATF hold a plenary meeting three times a year. At the conclusion of these meetings, FATF makes a statement identifying two sets of countries:

- The "Black List" is a list of countries that are thought to pose a high risk of money laundering, terrorist financing and proliferation financing, due to their significant strategic deficiencies in that regard. FATF calls on its members and other jurisdictions to apply enhanced due diligence and, in the most serious cases, to apply countermeasures to these countries. This list of "high-risk jurisdictions subject to a call for action" has come to be known as the Black List.

- The "Grey List" is a list of "jurisdictions under increased monitoring". These are countries which have made a commitment to address strategic deficiencies regarding money laundering, terrorist financing and proliferation financing in an agreed period and are subject to increased monitoring. This list of countries is often referred to as the Grey List.

These statements are made following an in-depth and lengthy evaluation of a country's compliance with the FATF recommendations. Evaluations are conducted by legal and financial experts from peer countries, FATF Secretariat officials, FATF-Style Regional Bodies, and officers from organisations like the International Monetary Fund or the World Bank. As the evaluations are highly technical, market actors, governments, and international organisations take the lists into account when making decisions on where to allocate capital, as explored further below.1

After the third plenary meeting of 2023, which closed on 27 October:

- FATF's Black List statement declared that the Democratic People's Republic of Korea and Iran were still identified as requiring the application of countermeasures. Myanmar, too, remained on the list as warranting enhanced due diligence due to serious strategic deficiencies in countering money laundering, terrorist financing and proliferation financing.

- Bulgaria was announced as the latest addition to the Grey List, alongside 22 other previously listed countries. Albania, the Cayman Islands, Jordan and Panama were removed from the Grey List.

To be removed from these lists, the countries will need to satisfy FATF that they have addressed the weaknesses that have been identified in their controls against money laundering, terrorist financing and proliferation financing.

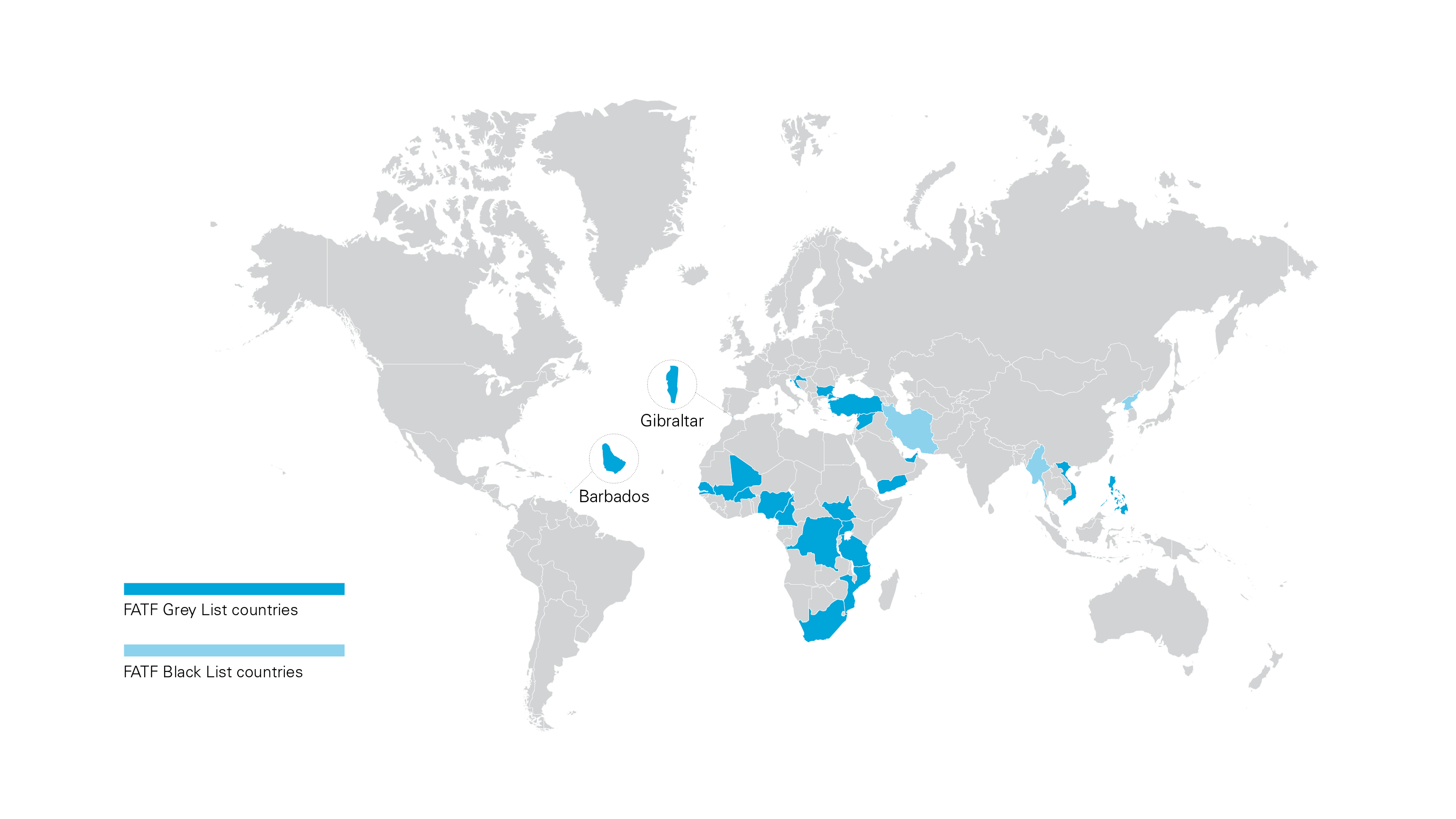

The following map shows the 26 countries which are currently on FATF's Black List or Grey List.

FATF Black List Countries (Democratic People's Republic of Korea, Iran and Myanmar) and Grey List Countries (Barbados, Bulgaria, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Croatia, Democratic Republic of Congo, Gibraltar, Haiti, Jamaica, Mali, Mozambique, Nigeria, Philippines, Senegal, South Africa, South Sudan, Syria, Tanzania, Türkiye, Uganda, United Arab Emirates, Vietnam and Yemen) shown above.

The History of the FATF Lists

FATF's remit has grown over the years. Initially, after its 1989 creation, it was focused on money laundering, but in 2001 its mandate expanded to cover terrorist financing in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks in the U.S. In 2012, FATF expanded its remit again to cover proliferation financing and issued recommendations relating to weapons of mass destruction.2

This practise of Black- and Grey-Listing countries has gone through a series of iterations. While FATF focuses on a process of making recommendations, mutual evaluation and peer review, it is not focused on maximizing its enforcement capacity. In 2000, over a decade after FATF had come into being, FATF implemented a 'Non-Cooperative Countries and Territories' process.3 The initial June 2000 list had 13 countries on it and members stopped adding jurisdictions in 2002. By 2006, only one country, Myanmar, remained on the list.4 This did not last long. In 2010, the list made a come-back when FATF instituted the current process.5

The European Union List

The European Union produces a list of third-country jurisdictions which have strategic deficiencies in their national AML / CFT regimes and that pose significant threats to the financial system of the Union (the "EU High-Risk Third Countries List"). This list is a legal requirement arising from the Fourth Anti-Money Laundering Directive, which came into force in 2015.6 There is a large degree of duplication across the FATF Black and Grey Lists and the EU High-Risk Third Countries List, with 88% of FATF-listed countries also included in the EU High-Risk Third Countries List.7

Practical Implications

In its annual report of 2014-2015, FATF described the naming of non-compliant countries as a "powerful tool" that "puts pressure on the countries in question to address these deficiencies in order to maintain their position in the global economy."8 FATF states on its website that its "process to publicly list countries with weak AML / CFT regimes has proved effective."9

Both Black- and Grey-Listing have consequences for a country's economy and financial system. It can restrict cross-border transactions, lead to difficulties for a state obtaining credit, and limit inward foreign investment. In addition to economic consequences, Black- and Grey-Listing damages a country's reputation and reduces its international standing. Interestingly, the three countries on the Black List (Iran, the Democratic People's Republic of Korea and Myanmar) are all subject to international sanctions packages.

In particular, the consequences experienced by countries placed on the Grey List have been the subject of various economic studies.10 Some of the broad conclusions are interesting and demonstrate the potentially significant economic damage caused to a jurisdiction as a result of Grey-Listing:

- There is a notable reduction in the ratio of foreign direct investment to GDP (on average, 2% when a country has low FATF scores, and reductions of up to 5% on average if the country is included on the Black List11).

- An analysis of SWIFT data between 2004 and 2014 indicated that Grey-Listing by FATF appears to lead to a reduction of up to 10% in payments received by the listed country from the rest of the world. This can be seen as representing sizeable losses for affected countries. The study did not identify any linked reduction in money leaving the countries that had been listed.12

- An analysis of bank inflows between 2010 and 2015 found that listing leads to a statistically significant and substantively large decrease in cross border liabilities of approximately 16%.13

- A recent study, which used machine learning techniques, found that there was a significant effect of Grey-Listing on capital inflows, with a decline on average of 7.6% of GDP when the country is added to the Grey List. The results also suggest that foreign direct investment inflows decline on average by 3%, portfolio inflows decline on average by 2.9% and other investment inflows decline on average by 3.6% of GDP.14

A driver of this economic damage is the reaction of banks and other firms regulated from an AML / CFT perspective (i.e., financial gate-keepers) which are required to consider a country's Black- or Grey-Listed status as part of their AML / CFT policies and procedures. To comply with domestic law, firms will need to undertake a higher level of due diligence regarding transactions or relationships involving parties based in listed countries. This acts as a disincentive to work with clients from such countries, as additional resources must be devoted to managing those relationships. Enhanced due diligence brings with it extra costs in terms of external spend, for example if a corporate intelligence report from an external provider is sourced,15 not to mention additional time required from the compliance team and relevant relationship managers. This can even lead to the termination of certain classes of relationships by regulated firms, a practice known as "de-risking".

Getting Off a List

Given the economic and reputational impacts resulting from a listing, countries are likely to be incentivised to take steps so that they are removed from the Lists. In order to get off the Black List or Grey List, a country must undertake a wide-ranging remediation exercise to deal with the deficiencies FATF has identified in its AML, CFT and proliferation financing framework, including from a legal perspective. Listed countries have reason to be optimistic. Of the 98 countries which had been listed by FATF up until October 2023, 76 have been removed.16

It is becoming more common for countries, usually via their Ministry of Finance, to seek support from external advisers in relation to their remediation process to be removed from the Grey List. White & Case have advised numerous states on their engagement with FATF processes.

1 Morse, "Blacklists, Market Enforcement, and the Global Regime to Combat Terrorist Financing", International Organization 73, July 2019.

2 https://www.fatf-gafi.org/en/the-fatf/history-of-the-fatf.html

3 Case-Ruchala and Nance, "FATF blacklists don't work the way you think they do", Paper prepared for presentation at the 2nd Annual Empirical Anti-Money Laundering Conference, January 2021.

4 FATF Annual Report 2005-2006, June 2006.

5 Ibid

6 Directive (EU) 2015/849 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 May 2015.

7 As at the conclusion of the FATF October 2023 plenary. Three countries Grey-Listed by FATF are not found on the EU High-Risk Third Countries List: Bulgaria, Croatia and Turkey, and the EU has designated six further countries as "high-risk" which are not included in the FATF lists (Afghanistan, Cayman Islands, Jordan, Panama, Trinidad and Tobago, and Vanuatu). Although we note that the Cayman Islands, Jordan and Panama were only recently removed from the FATF list on 27 October 2023.

8 FATF Annual Report 2014-2015, June 2015, p. 19.

9 https://www.fatf-gafi.org/en/countries/black-and-grey-lists.html

10 For a helpful overview of the work in this area, a useful starting point is Kida and Paetzold, "The Impact of Gray-Listing on Capital Flows: An Analysis Using Machine Learning", International Monetary Fund Working Paper, May 2021.

11 "Measuring the direct effects of low FATF scores… the ratio of investment (fixed capital formation) can be reduced at least 2 percent (on average) when a country is poorly rated. Similarly, the country could lose investment at least in 5 percent (on average) when it has been included in the blacklist." Farias and De Almeida, "Does saying 'Yes' to Capital Inflows necessarily mean good business? The effect of antimoney (sic) laundering regulations in the Latin American and Caribbean economies", Economics and Politics, March 2014.

12 Collin, Cook and Soramaki, "The impact of Anti-money laundering regulation on payment flows: evidence from SWIFT data" Centre for Global Development Working Paper 445, December 2016.

13 Morse, "Blacklists, Market Enforcement, and the Global Regime to Combat Terrorist Financing", International Organization 73, July 2019.

14 Kida and Paetzold, "The Impact of Gray-Listing on Capital Flows: An Analysis Using Machine Learning", International Monetary Fund Working Paper, May 2021.

15 Artingstall, Dove, Howell and Levi, "Drivers & Impacts of Derisking", A study of representative views and data in the UK, by John Howell & Co. Ltd. for the Financial Conduct Authority, February 2016.

16 https://www.fatf-gafi.org/en/countries/black-and-grey-lists.html - the sample size of total countries subject to review was 125. An additional four countries were removed in October 2023, increasing the total to 76.

White & Case means the international legal practice comprising White & Case LLP, a New York State registered limited liability partnership, White & Case LLP, a limited liability partnership incorporated under English law and all other affiliated partnerships, companies and entities.

This article is prepared for the general information of interested persons. It is not, and does not attempt to be, comprehensive in nature. Due to the general nature of its content, it should not be regarded as legal advice.

© 2023 White & Case LLP

View full image (PDF)

View full image (PDF)