On November 18, 2025, in Duke University v. Sandoz Inc. (No. 24-1078), the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit reversed a District of Colorado judgment and overturned $39 million of damages awarded by a jury, holding that asserted claim 30 of U.S. Patent No. 9,579,270 is invalid for lack of adequate written description. The panel concluded that no reasonable jury could find that the '270 patent's specification showed possession of the claimed subgenus of prostaglandin F (PGF) analogs used to grow hair. This continues the court's trend of applying stringent standards under 35 U.S.C. § 112.

Allergan asserted a broad genus claim on hair loss drugs

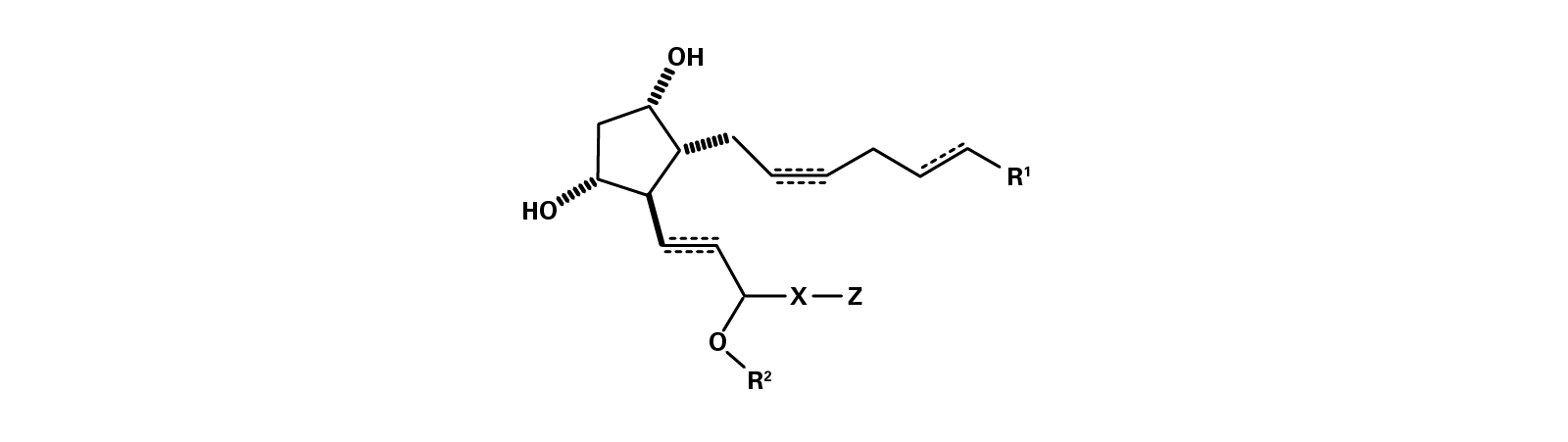

The '270 patent, owned by Duke University and licensed to Allergan, claims compositions and methods for treating hair loss using PGF analogs. Allergan markets and sells Latisse®, a topical treatment for eyelash hair growth that contains bimatoprost. Bimatoprost is a PGF analog with an ethyl amide at its "action end" (C1 location) and phenyl at its "omega end" (Z position). Claim 30 covers active ingredients with this structure:

Sandoz manufactures and sells a generic version of Latisse®. In 2018, Allergan sued Sandoz, alleging Sandoz's generic product infringes claim 30.1 Sandoz stipulated to infringement but attempted at trial to prove that claim 30 is invalid for lack of adequate written description. After hearing competing expert testimony, the jury found claim 30 not invalid, and the district denied Sandoz's requests for JMOL and a new trial.

Federal Circuit finds claim 30 describes a vast subgenus of compounds without describing shared common structural features

Even though written description is a question of fact requiring clear and convincing evidence, and despite deference to the jury verdict—imposing a "doubly high" burden on Sandoz—the Federal Circuit reversed.2

The court reiterated that a patentee seeking to claim a genus or subgenus of chemical compounds must disclose either 1) a representative number of species within that genus or subgenus or 2) common structural features that would guide a person of skill in the art to the claimed genus or subgenus.

Allergan did not argue that the patent disclosed a representative number of species within claim 30's scope, and the court noted the specification did not expressly disclose even one claimed embodiment.3 Instead, Allergan argued that claim 30 satisfies the "common-structural features" test because it discloses three features that are common to all members of the claimed subgenus: a characteristic prostaglandin hairpin; amides at the C1 position; and a phenyl ring at the omega end.4

The Federal Circuit disagreed, finding that the patent's disclosure of "two prostaglandin hairpin structures" involved a generic feature shared by all prostaglandins, and that Allergan failed to identify how the hairpin structure is unique to the claimed subgenus of compounds.5 Further, claim 30 discloses a C1 location with 13 categories of options—nine of which require additional choices by a person skilled in the art to create a qualifying compound. The court also noted that the specification pointed away from the combinations recited in claim 30 as it listed five of the 13 options for C1 as "preferred or more preferred." Yet, those five options did not include the "amide" option needed to reach the claimed invention.6

The court rejected Allergan's argument that the specification satisfied the written description requirement as it taught methods for compound synthesis that included synthesizing the required amides at C1. The court noted that the specification did not indicate amides should be preferred at C1.7

The court conducted a similar analysis for the specification's disclosure of eight categories of options for the Z position. The specification outlined eight categories of compounds for the Z position. However, a person skilled in the art needed to specifically select one category of the eight in order to create the claimed invention, and the specifications did not guide a skilled artisan to select the necessary category.8

Citing its decision in Regents of the Univ. of Minn. v. Gilead Scis., Inc., the court stated that "'[f]ollowing [such a] maze-like path, each step providing multiple alternative paths, is not a written description.'"9 The court held that a skilled artisan could not visualize or recognize the claimed subgenus from the described branching options, and the evidence compelled a conclusion of inadequate written description by clear and convincing evidence.

Duke v. Sandoz reinforces a stringent application of the written description requirement to chemical subgenus claims. Patent specifications that fail to disclose either a representative number of species or common structural features among the claimed subgenus/genus will likely fail the written description requirement.

Key Takeaways

- Chemical genus and subgenus claims need to identify and disclose either a representative number of species within the claimed scope or common structural features with blaze marks that direct a skilled artisan to the claimed genus or subgenus;

- Specifications that enumerate categories at multiple variable positions—without prioritizing the combinations that actually define the claimed genus or subgenus—risk failing the written description requirement;

- Specifications that state preferences pointing away from the claimed combination cut against possession of the claimed subgenus.

1 Duke Univ. v. Sandoz Inc., No. 24-1078, slip op. (Fed. Cir. Nov. 18, 2025).

2 Id. at 6.

3 Id. at 9.

4 Id.

5 Id. at 10.

6 Id. at 13.

7 Id. at 15.

8 Id. at 15.

9 Id. at 13 (quoting 61 F.4th 1350, 1355 (Fed. Cir. 2023)).

Christhy Le (White & Case, Law Clerk, Silicon Valley) co-authored this publication.

White & Case means the international legal practice comprising White & Case LLP, a New York State registered limited liability partnership, White & Case LLP, a limited liability partnership incorporated under English law and all other affiliated partnerships, companies and entities.

This article is prepared for the general information of interested persons. It is not, and does not attempt to be, comprehensive in nature. Due to the general nature of its content, it should not be regarded as legal advice.

© 2025 White & Case LLP

View the full image here (PDF)

View the full image here (PDF)