Mining and mineral resources have always been a lightning rod for economic and political power, and the modern era is no different – 2025 has seen a market acceleration in states and private companies vying for the world's critical minerals to promote economic and political strength. As demand for energy and critical minerals grow, driven in part by advancements in AI and the energy transition, as well as an increased focus on defense, stakeholders are looking beyond traditional mining strategies to the deep ocean floor, hoping to open new avenues for growth in this uncharted (and largely ungoverned) territory. The viability of these ventures turns on several factors – including the pace of technological advancements, shifting demand for the relevant minerals, and ongoing geopolitical machinations. Here we examine the history and future of the competing regulatory frameworks – those of the United Nations and the United States – and consider what this means for deep sea mining in practice.

The underdeveloped and incompatible regulatory frameworks for deep sea mining lag behind the growing market and geopolitical enthusiasm for it.

The underdeveloped and incompatible regulatory frameworks for deep sea mining lag behind the growing market and geopolitical enthusiasm for it. But deep sea mining is not alone: we see this theme of increasing regulatory uncertainty and regulatory competition playing out across multiple facets of critical minerals supply chains globally.

1. The United Nations’ Convention on the Law of the Sea

Deep-sea mining involves extracting minerals and sediment from the seafloor at depths greater than 200 meters.1 The British vessel HMS Challenger was the first to retrieve samples of certain mineral nodules (slow forming, potato-sized mineral deposits) from depths of 15,600 feet,2 and starting in the 1950s, private companies began prospecting the seafloor for these nodules in earnest,3 with key zones of high nodule concentration identified by the early 1970s.4

The initial stages of commercial exploration coincided with growing territorial tensions as domestic oil exploration moved further offshore. Historically, nations abided by the "freedom-of-the-seas" doctrine, which saw the majority of the ocean to be a common resource (other than a narrow area near a given nation's coastline). However, in response to postwar scarcities and the shifting importance of critical minerals in the new atomic age, in 1945, U.S. President Harry S. Truman unilaterally extended U.S. jurisdiction over its continental shelf's natural resources.5 The move led to a race among various other nations to replicate similar regulatory models and assert sovereignty over what they perceived as their own territorial waters and continental shelves.6

In response to looming territorial conflict over oceanic resource extraction, the international community, including 159 nations, adopted the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea ("UNCLOS") in 1982, establishing a framework for regulating activities in the world's oceans.7 Notably, UNCLOS established the concept of "exclusive economic zones" ("EEZ"), areas which extend up to 200 miles from the shore of any given state in which that state has sovereign rights to explore, exploit, conserve and manage the natural resources of the seabed (and overlying waters) and subsoil. UNCLOS also framed the resources of the seabed beyond the limits of national jurisdiction as "the common heritage of mankind", and therefore the common responsibility of all nations to safeguard. However, the United States did not adopt UNCLOS.

UNCLOS created the International Seabed Authority ("ISA"), when the UNCLOS came into force in 1994, to regulate and control mineral-related projects within its jurisdiction, which includes the area outside of EEZ waters.9 The ISA was tasked to create permitting regimes for both exploratory and extractive permits for mining in the Area – however, in its thirty years of existence, the ISA has focused solely on exploratory permits and contracts. As of June 11, 2025, the ISA has entered 31 15-year exploratory contracts with 22 contractors, including public and private entities from a diverse array of countries, including India, China, and various island nations for whom their EEZ comprises the vast majority of their territorial rights (e.g. the Cook Islands, Nauru, and Kiribati).10 Prior to 2010, exploration contracts were primarily undertaken by national governmental agencies.11 Starting in 2010, a new wave of contracts began, including private sector contracts sponsored by Member States.12

Despite the growing number of exploratory ISA contracts, the ISA has not developed a regulatory regime to address deep-sea mineral extraction – since 2011, the ISA has been debating a regulatory framework for extraction but has not yet been able to find consensus and begin issuing extraction contracts. In 2021, the Republic of Nauru jump-started the process when it sponsored a private company's application to mine in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone.14 Nauru's application on behalf of this project (developed by a subsidiary of The Metals Company ("TMC"),15 triggered a two-year timeline for the ISA to establish its deep-sea mining policy, as included in the 1994 Agreement relating to the implementation of Part XI of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea of 10 December 1982, stating that upon an application for commercial exploration,16 the ISA Council is required to produce the necessary regulations for commercial exploration. Given that the Republic of Nauru and TMC submitted their application in 2021, the ISA was required to release the relevant regulations by 2023. The ISA did not release a regulatory framework in 2023, and instead chose to extend the deadline to 2025. As of June 2025, nothing has been issued.

If private developers thought that Nauru and TMC could prompt the ISA into issuing a regulatory framework for commercial extraction, they were mistaken – and once the ISA allowed itself one extension, developers keen to begin investing in deep sea mining were concerned that more could follow. Attention thus turned to the most prominent nation that was not a signatory to UNCLOS, and therefore not technically bound by the ISA's regulations – the United States.17

2. The United States’ Regulatory Framework

When UNCLOS was being debated in the 1980s, then-President Ronald Reagan's administration disagreed with the principle of considering any physical space as "common heritage of mankind," as it conflicted with the administration's free-market philosophy.18 While the U.S. government has since recognized aspects of UNCLOS as customary law, the U.S. has never ratified UNCLOS or any associated agreements, including the Agreement on Part XI of UNCLOS, and there appears to be little congressional push to do so.19

The United States passed the Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resources Act ("DSHMRA") in 1980, which purported to promulgate a regulatory framework (administered by the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration ("NOAA") for United States' private companies and government agencies to explore and extract from the deep seabed beyond the United States' EEZ. The DSHMRA positioned the United States in direct tension to the ISA from its inception – however, very few permits have been issued by NOAA in the decades since the DSHMRA's passing. Currently, two exploration permits are held by Lockheed Martin, and no commercial extraction permits have been issued at all.

However, as part of the overall policy imperative by the United States to focus on self-sufficiency in critical minerals production, the Trump administration has signalled a desire for the United States to emerge as a central figure in deep-sea mining, encapsulated by the Executive Order, "Unleashing America's Offshore Critical Minerals and Resources" dated April 24, 2025 (the "EO").20 The EO directs NOAA to expedite the permitting timelines for projects within and beyond the United States' EEZ, and directs the Secretary of Commerce (in coordination with the heads of other relevant agencies) to identify opportunities for private sector investment within and beyond the United States' EEZ as well as in the EEZ's of other countries which may seek to collaborate with the United States on critical mineral extraction (see also our summary of the EO published at the time of its issuance here).21

3. It's not just the US and the UN: Saudi Arabia and other countries ramping up their deep sea mining efforts

As both the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the US seek to secure sustainable supply chains for critical minerals, deep-sea mining has emerged as a focal point in their collaborative efforts.

In the recent efforts to strengthen the strategic economic partnership between the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the US, more than 100 agreements and memorandums of understanding were signed during the Saudi- US Investment Forum ("Forum"), amounting to approximately USD 600 billion investment commitments. These cover a range of key sectors, including critical minerals.25 The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, which is also a signatory to UNCLOS, is looking to unlock potential critical mineral opportunities, including deep sea mining, through strategic alliances with global players. To that end, the Ministry of Industry and Mineral Resources in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the Department of Energy of the United States signed a Memorandum of Cooperation during the Forum that aims at establishing a cooperation framework on mining and mineral resources. This cooperation seeks to contribute to economic developments, diversification, and resilience of critical mineral supply chains.26 As both the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the US seek to secure sustainable supply chains for critical minerals, deep-sea mining has emerged as a focal point in their collaborative efforts. The Kingdom's deep sea mining endeavours could be an early case study for resolving the regulatory tensions we have identified; particularly if the Kingdom is able to successfully navigate both its UNCLOS membership and its collaboration with the US.

4. What is required for deep sea mining in practice?

4.1 Next Steps for Regulators: Unknown Unknowns

The gap in scientific research surrounding deep-sea mining makes its potential environmental impacts "incompletely understood."27 Regulators are tasked with establishing a regulatory framework flexible enough to respond to environmental and technical unknowns, while also establishing predictable standards that encourage long-term investment. All the while, the ISA faces heightened diplomatic tension as it balances the interests of its 169 member states.28

The knowledge gap creates uncertainty throughout the regulatory lifecycle of deep-sea mining projects. Beyond initial permitting, the same unanswered questions over relevant impact measurements affect the ongoing monitoring of projects. The scientific community has raised concerns tied to deep-sea mining, including sediment dispersal, destruction of habitats, and noise pollution.29 Without comprehensive and independent research on the potential impacts of these project, it may become harder for regulators to verify developers' claims related to projects' potential impacts, especially if regulators are not sufficiently equipped to support the process (including as technologies evolve).

4.2 Next Steps for Developers: Known Unknowns

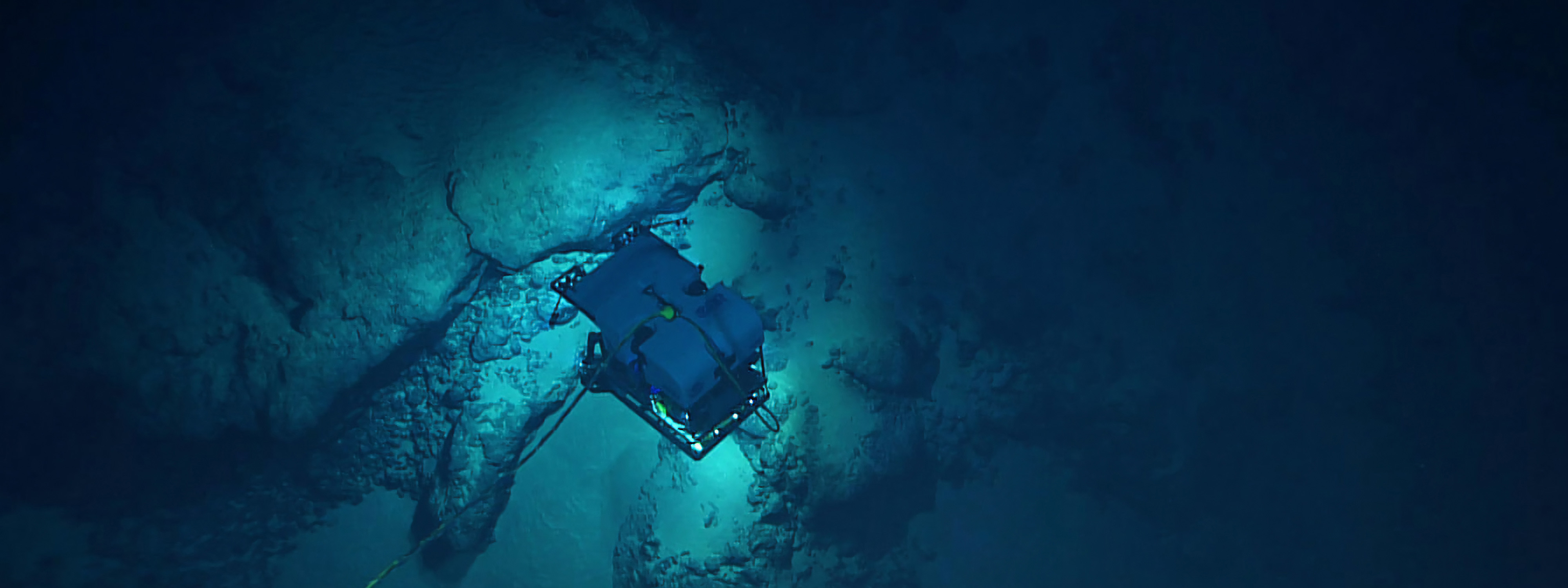

While there have been significant advancements in deep-sea mining technologies, such as Impossible Metals' development of autonomous underwater vehicles,30 developers are largely at the proof-of-concept stage.31 No technology has successfully supported long-term commercial deep-sea mining projects. The intersection between unknown regulatory risks, environmental risks and novel technologies creates uncertainty for financial investors.32 Market leaders, like Google and Apple, have called for a moratorium on deep-sea mining activities to date and have committed to not finance such projects due to the unknown environmental, social, and economic impacts of deep sea mining.33

Non-U.S. developers may face regulatory, financial, and political consequences if they engage outside the ISA framework. For example, developers who do not receive permitting from the ISA to engage in deep-sea mining beyond a nation's EEZ may violate international law.34 Existing ISA contractors engaging in commercial deep-sea mining activities within their license's designated area for exploration could constitute contractual infringement and could violate ISA regulations and provisions of UNCLOS.35 Additionally, developers must be aware of the possibility of arbitration, especially as it relates to jurisdictional and investor-state disputes.36

4.3 Next Steps for Countries: Unknown Knowns

The ISA disapproves of any attempt to unilaterally engage in deep-sea mining beyond a nation's EEZ.37 Yet, the ISA has not set a clear deadline for its own promulgation of a comprehensive licensing regime for extraction. In the meantime, nations such as Norway, Japan, and the Cook Islands are pursuing deep-sea mining within their EEZs38 - and other nations may choose to collaborate with the United States under the purview of the DSHMRA. Deep-sea mining within nations' EEZs presents a more predictable regulatory strategy, but projects face similar technical and environmental uncertainty, and there is no guaranty that environmental impacts would be limited to the state undertaking the mining initiative.

5. Deep-Sea Mining: A small (but growing?) aspect of the critical minerals supply chain

The Trump Administration's April 2025 EO marks a potential shift in momentum towards deep-sea mining outside nations' EEZs

Despite the opportunity, investors should fully assess the medium- to long-term risks associated with the uncertainties and inconsistencies in international regulatory regimes, unknown environmental costs, and fluctuating markets for critical minerals. Deep-sea mining projects are decades-long endeavors and thus require long term regulatory stability in order to be viable. Therefore, changes and tensions in national and international regulatory models must be analyzed within the broader context of global governance, scientific capacity, and market changes.

In theory, commercial deep-sea mining projects could expand nations' access to critical minerals, supporting energy transition and increased independence. However, without significant investment in national onshore processing capacity, most nations will remain import-dependent on China. As nations seek energy and critical mineral independence, resource extraction should be paired with investments in national onshore processing; otherwise, nations will remain dependent on other nations.

Reem Alomran (Associate, White & Case), Abdulrahman Alkhudairy (Associate, White & Case) and Anne Campbell (Summer Associate, White & Case) contributed to the development of this publication.

1 www.congress.gov/crs-product/R47324

2 www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/convention_historical_perspective.htm; www.isa.org.jm/exploration-contracts/

3 www.npr.org/2025/03/27/nx-s1-5336319/international-deep-sea-mining-critical-metals-seabed; www.wri.org/insights/deep-sea-mining- explained

4 www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/convention_historical_perspective.htm

5 www.gc.noaa.gov/documents/gcil_proc_2667.pdf

6 www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/convention_historical_perspective.htm

7 www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/convention_historical_perspective.htm; www.un.org/depts/los/LEGISLATIONANDTREATIES/status.htm

8 www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/convention_historical_perspective.htm

9 www.congress.gov/crs-product/R47324; https://www.isa.org.jm/about-isa . (Article 156; 2) Article 1(1)(1))

10 www.isa.org.jm/exploration-contracts/; https://www.isa.org.jm/exploration-contracts/polymetallic-nodules/.

11 Exploration Contracts

12 ISA_Secretary_General_Annual_Report_2024_Chapter5.pdf

13 https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R47324

14 https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R47324

15 https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R47324

16 https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/agreement_part_xi/agreement_part_xi.htm

17 https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R47324

18 US will not sigh Sea Law Treaty

19 www.congress.gov/crs-product/R47324 https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/agreement_part_xi/agreement_part_xi.htm

20 www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/04/unleashing-americas-offshore-critical-minerals-and-resources

21 www.whitecase.com/insight-alert/new-executive-order-seeks-increase-american-extraction-minerals-through-deep-sea

22 The Metals Company to Apply for Permits under Existing U.S. Mining Code for Deep-Sea Minerals in the High Seas in Second Quarter of 2025. See also Deep Seabed Hard Minerals Mining

23 SG_Statement-on-the-US-Executive-Order-Unleashing-the-Offshore-Critical-Minerals-and-Resources-of-America.pdf

24 Artemis-Accords-signed-13Oct2020.pdf

25 saudipedia.com/en/article/4708/economy-and-business/economic-affairs/saudi-us-investment-forum

26 uqn.gov.sa/archive?p=27174

27 www.congress.gov/crs-product/R47324

28 www.congress.gov/crs-product/R47324

29 www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0308597X18306407; https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R47324

30 https://impossiblemetals.com/technology/robotic-collection-system

31 Why Deep-Seabed Mining Needs a Moratorium.

32 www.wsj.com/articles/a-miner-goes-bust-another-goes-solo-as-progress-on-u-n-seabed-rules-stalls-cba45638

33 www.stopdeepseabedmining.org/endorsers/; https://www.stopdeepseabedmining.org/statement

34 www.isa.org.jm/faq-for-media/#:~:text=and%20without%20ISA.-,Q.,regulations%20are%20ready%20for%20adoption

35 www.isa.org.jm/faq-for-media/#:~:text=and%20without%20ISA.-,Q.,regulations%20are%20ready%20for%20adoption

36 www.italaw.com/cases/7261;https://pca-cpa.org/cn/cases/37 . See also https://pca-cpa.org/cn/cases/7, https://academic.oup.com/jel/article-abstract/27/3/529/408870?redirectedFrom=PDF

37 www.isa.org.jm/faq-for-media/#:~:text=and%20without%20ISA.-,Q.,regulations%20are%20ready%20for%20adoption

38 https://deepseamining.ac/article/50#gsc.tab=0

White & Case means the international legal practice comprising White & Case LLP, a New York State registered limited liability partnership, White & Case LLP, a limited liability partnership incorporated under English law and all other affiliated partnerships, companies and entities.

This article is prepared for the general information of interested persons. It is not, and does not attempt to be, comprehensive in nature. Due to the general nature of its content, it should not be regarded as legal advice.

© 2025 White & Case LLP