Vietnam is one of the fastest growing economies in Asia. Like other emerging markets, its electricity generating capacity has been under pressure to keep up with demand, which has increased by approximately 10% annually in recent years.

Vietnam has traditionally relied on coal as its primary source for generating electricity. The Power Development Plan VII, published in 2016, planned for coal to remain the key source of energy in the country, with coal production capacity projected to more than double its current levels by 2030. In recent years, however, Vietnam's coal power project development has slowed, and renewable energy and natural gas have emerged as important components of Vietnam's future energy mix.

The demand for natural gas presents significant LNG opportunities in Vietnam not only due to the growth in demand for energy, but also because gas production in Vietnam is expected to start declining from 2025 and offshore exploration in the South China Sea is facing challenges. In anticipation of the declining supply of natural gas from domestic sources, Vietnam is expected to become an LNG importer as early as 2021. This will require significant upfront investments to build infrastructure across the LNG-to-power chain and Vietnam will be looking to strategic investors and sponsors for foreign capital and expertise.

A key area of focus will be the legal framework for the gas market in Vietnam. As recognised in the Gas Master Plan issued in January 2017, the current legal framework requires further development. It currently reflects the historically dominant position held by state-owned enterprises across the power generation, transmission and supply chain, as well as the reality that Vietnam's gas reserves have been sufficient to meet domestic demand. As Vietnam transitions into an LNG importer, policies on LNG import prices (eg, to allow the ability to pass on increases in gas prices to consumers), technical standards for LNG infrastructure, and the liberalisation of the electricity and gas markets, among others, will be important considerations in the creation of a transparent and competitive market.

Foreign investment will be essential to achieve Vietnam's development ambitions and, encouragingly, the Vietnamese Government has shown a readiness to pursue regulatory reform to create a stable legal framework in order to attract foreign investment, particularly in sectors where foreign investment can be leveraged to expedite implementation of Vietnam's ambitions.

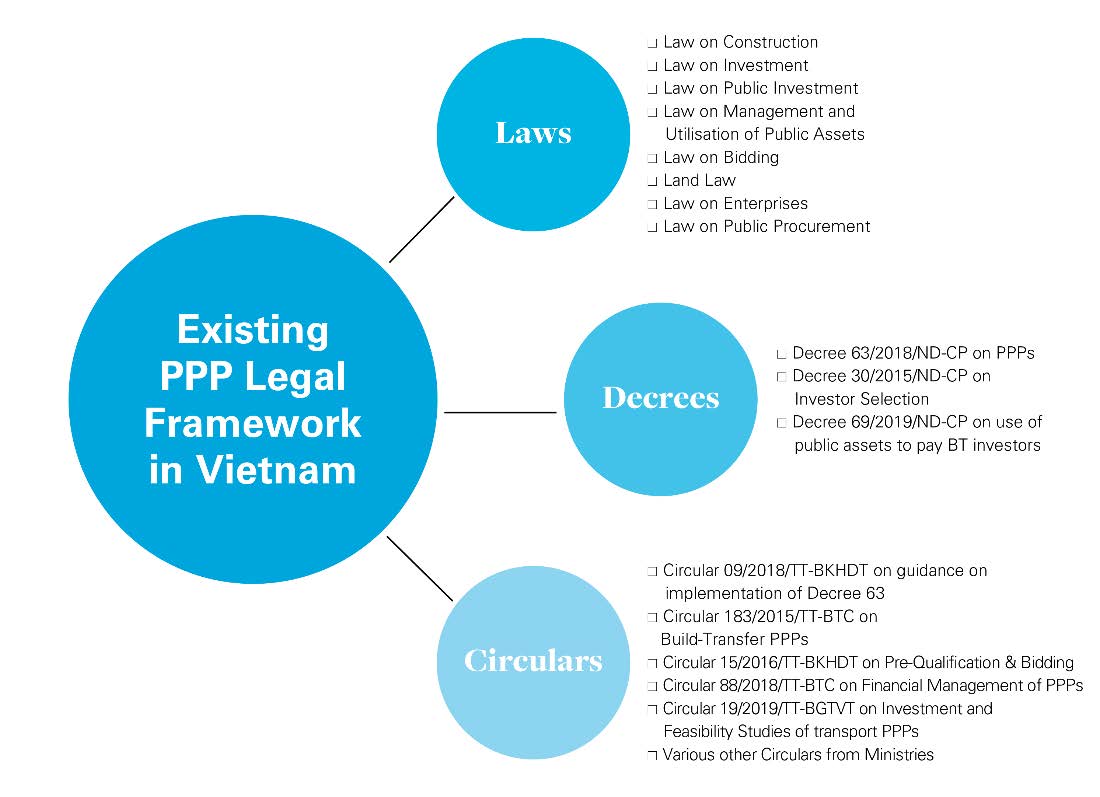

This is evidenced in the government's plans to liberalise the electricity market in phases from 2016 to 2023 and more recently, in 2020, its changes to Vietnamese investment laws and the codification of a public-private partnership law for the first time in Vietnam. For investors in LNG-to-power projects, the enhanced possibility of a PPP project development strategy, as has been seen in other emerging markets, is a positive development.

The Law on Public-Private Partnership (PPP Law) was ratified on June 18 2020 and will come into effect on January 1 2021.This marks the codification of regulations on PPP projects, replacing a web of existing legal instruments. The PPP Law specifies a narrower list of five defined sectors to which it applies compared with its predecessor Decree 63/2018/ND-CP on Public Private Partnership Investment Form, Decree 63, including power grids and power plants. Subject to limited exceptions, a minimum threshold of D200bn in project value applies – this should not be an issue for most LNG infrastructure projects as these would typically require significant upfront capital investment.

Figure 1 - Existing Legal Framework in Vietnam

The PPP Law raises a number of important considerations for investors and lenders. First, government guarantees for performance or payment obligations of state-owned enterprises (for example, to supply fuel or to purchase electricity from BOT power plants) were contemplated in Decree 63. The PPP Law is silent in this regard other than with respect to government guarantees to be given for foreign currency risk (for 30% of revenues after deducting expenses), access to land, exercise of land use rights, access to public services and public facilities, and rights to mortgage assets. These express guarantees for foreign currency risk are positive features under the PPP Law. However, the lack of broader performance or payment guarantees, and only partial coverage of foreign currency risk, will require careful assessment. The possibility of successful project-by-project negotiation with the government on these issues will be a key focus.

Second, the PPP Law introduced a new revenue risk-sharing mechanism. If actual revenue is greater than 125% of the revenue forecast in the financial model agreed in the PPP contract, the government will take a 50% share of the revenues in excess of the 125% threshold. In a low case scenario, the government will share 50% of losses below 75% of the forecast revenue – but only if certain conditions are met, including that a change in the government's plans, policies or relevant laws led to the revenue shortfall and the same minimum revenue threshold cannot be met despite implementation of other measures, including tariff adjustments and/or extensions to the concession term. The attractiveness of this structure to investors in LNG-to-power projects remains to be tested, as does its applicability in the context of take-or-pay arrangements.

Other notable provisions in the PPP Law include framework provisions for various methods of contribution of state capital to a PPP project, the government's proposal to provide standard form PPP contracts, the requirement on investors to provide a bid security between 0.5% and 1.5% of the project value in addition to the performance security required for 1% to 3% of the project value and the requirement for the governing law of all PPP contracts to be the laws of Vietnam. While the PPP Law contains certain improvements over the previous instruments, there are still important areas for investors' and lenders' consideration. Continued engagement with the government as to the specific application of these requirements on a project-by- project basis and on the development of guidance and implementing regulations for the PPP Law is expected.

Another key issue that will impact the development of the LNG-to-power sector in Vietnam is its electricity pricing structure. The changing dynamics in the global LNG market have resulted in market players seeking greater flexibility in contractual terms. Shorter and more flexible terms could benefit buyers, but these arrangements typically come at the cost of pricing certainty. From an investor and lender perspective, it is desirable to pass on pricing risk to the end-consumer to the greatest extent possible. The importance of this feature is reflected by the adoption in other jurisdictions in the region of regimes that pass through costs ultimately to the end-users.

As state-owned enterprises have historically dominated the electricity market in Vietnam, and given that electricity tariffs can often be a sensitive consideration, electricity tariffs in Vietnam have remained relatively low. The government has recognised the need for liberalisation of the power market, and reforms have been implemented in phases for the generation market, the wholesale market and the retail market in Vietnam.

Steps taken to liberalise the electricity market, and create competitive market-based pricing to better reflect production costs, will encourage investment from the private sector. From the perspective of the LNG sector, these reforms are timely. Further development in electricity market regulations should ideally take into account a pricing structure that supports the development of a competitive LNG market, for example, pricing that allows costs (at least to a certain level) to be passed through to the end-users.

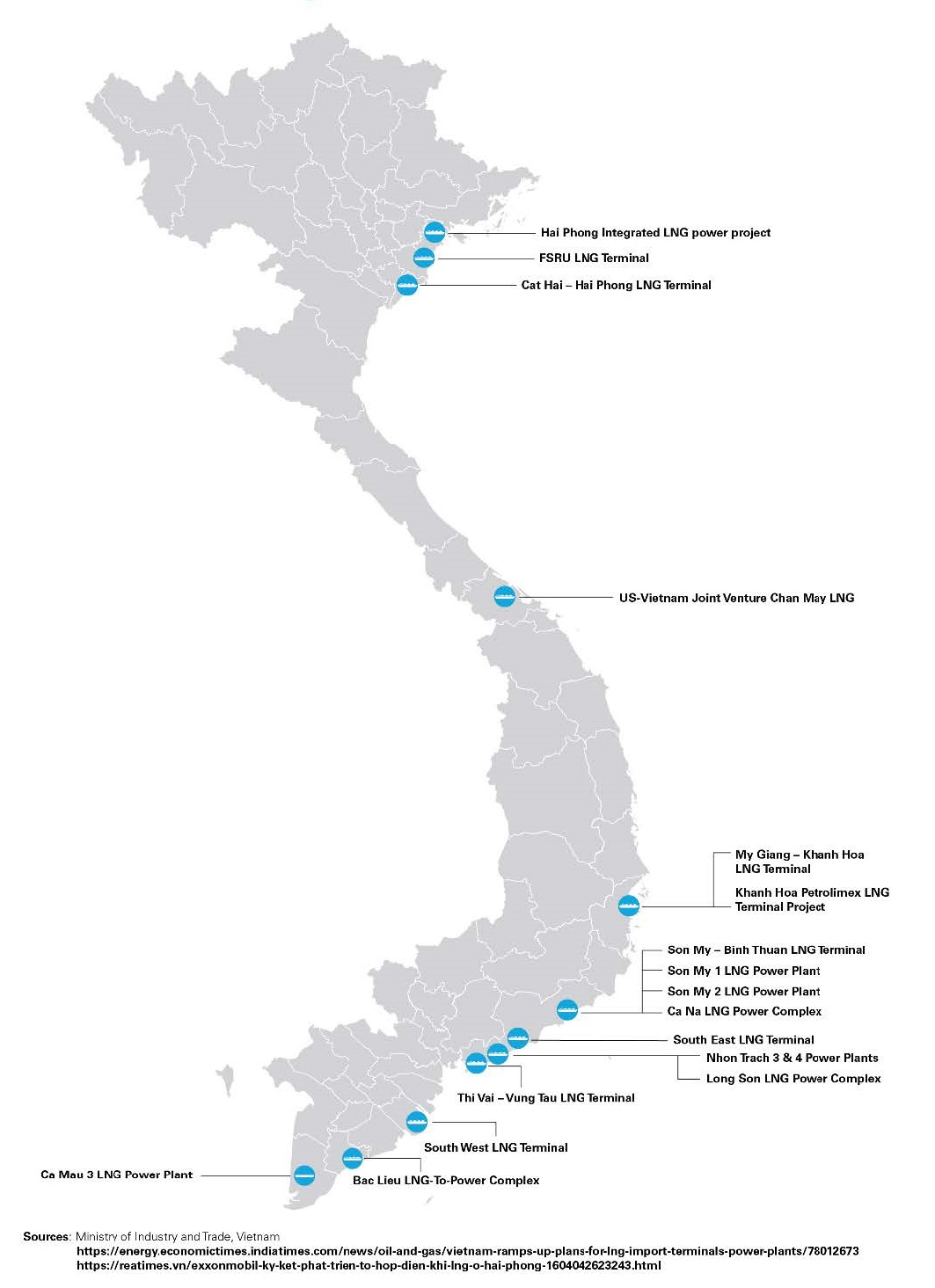

The Gas Master Plan 2017 anticipates gas demand in Vietnam to be 12bn–27bn m per annum from 2021 to 2025, and increasing to 23bn–31bn m per annum from 2026 to 2035. Of these volumes, it is envisaged that imports will start with 1bn– 4bn m per annum from 2021 to 2025, increasing to 6bn–10bn m per annum from 2026 to 2035. The Gas Master Plan also identified various projects to develop pipelines, terminals, regasification and storage facilities across each of the Northern, North Central Coast, South Central Coast, Southeast and Southwest regions. Further details on these LNG projects are expected to be set out in the Power Development Plan VIII that is to be issued later in 2020. The Institute of Energy of Vietnam has also compiled an ambitious list of 22 LNG-to-power projects planned for the next decade.

Figure 2 - Selected LNG Projects under the Gas Master Plan

A number these projects are gaining traction. For example, the first LNG terminal in Vietnam in the province of Ba Ria-Vung Tau is expected to start test runs and commence operations in 2021, upon which Vietnam will achieve the first importation of LNG into the country. Projects involving foreign investors are also forging ahead. ExxonMobil recently signed a memorandum of understanding with JERA for the development of a potential integrated LNG-to-power project in Hai Phong. Global investors continue to show strong interest in Vietnam, including, among others, US investors given the strategic synergies between the US and Vietnam in the LNG sector. A number of US greenfield LNG export facilities that have or will become operational in the coming years will push the US to become one of the largest (if not the largest) LNG exporters globally.

Foreign investors looking to invest in large-scale infrastructure projects globally are looking for a stable legal and regulatory framework and a risk allocation model that adequately allocates the risk between the private sector and government, and which will ultimately be acceptable to third-party lenders to the foreign investors. Ongoing regulatory reform will play an important part in supporting the growth of the LNG sector at a pace to meet Vietnam's energy ambitions.

This article was first published in Project Finance International on December 18, 2020. For further information please visit Project Finance International website.

This publication is provided for your convenience and does not constitute legal advice. This publication is protected by copyright.