"Competition forces you to evolve. When everything is easy, you don't improve". ― Rafael Nadal Parera, 1st Marquis of Llevant de Mallorca

Introduction

Over the past two decades, Spain's competition enforcement journey has been marked by bold ambition and uneven progress. Since the establishment of its modern competition framework in 2007, the CNMC (Comisión Nacional de los Mercados y la Competencia – "CNMC") quickly positioned itself as one of Europe's more proactive antitrust authorities, launching dawn raids, encouraging whistle-blowers, and imposing record fines that reshaped corporate behaviour in Spain. Yet alongside these early successes, challenges eventually emerged: leniency applications declined, courts demanded stricter evidence, and resource constraints began to weigh heavily on enforcement efforts.

As we trace the CNMC's path from 2004 to 2024, a complex picture comes into focus; one of technical expertise and broad jurisdictional reach, but also of fluctuating enforcement intensity influenced by changing political priorities and institutional pressures. The initial drive to match the vigour of leading European counterparts gradually gave way to a more cautious approach, marked by notable victories as well as significant setbacks. This evolving landscape tells the story of Spanish competition public enforcement as one shaped by both aspiration and restraint, a dynamic still unfolding, with its ultimate direction yet to be determined.

Spanish Antitrust Investigations from 2004 to 2024: An Expansive but Uneven Record

Since the formal establishment of Spain's modern competition law framework in the late 1990s, and particularly following the enactment of the 2007 Competition Act,1 the Spanish competition authority positioned itself as one of the most active enforcers within the European Union.

As early as 2008, Spain introduced a state-of-the-art leniency/whistle-blower programme designed to encourage individuals and companies to report cartel conduct from within. This model followed a proactive, deterrence-oriented approach that offered strong incentives to detect and disclose inside information. Drawing on the European Union's leniency framework,2 itself modelled on the U.S. antitrust immunity regime,3 Spain's leniency programme achieved remarkable early success.4 Yet beyond mere statistics, the programme's true impact resided in its ability to shift corporate culture in Spain. Boardrooms once characterised by watertight secrecy became arenas of calculated risk, where the prospect of immunity fostered internal whistle‑blowers and catalysed a cascade of self‑reported infringements. High‑profile cases, from clandestine bid‑rigging in public procurement to cartel agreements in industrial markets, fell apart as former conspirators raced to the authorities, transforming Spain's competition landscape almost overnight. In doing so, the leniency scheme not only dismantled entrenched cartels, but also triggered a cultural shift in the approach to enforcement.5

Crucially, the regime also reshaped M&A due diligence. Prospective buyers who uncovered evidence that a target company active in Spain was riddled with cartel violations found the leniency programme the perfect escape hatch to mitigate acquisition risks. By coming forward under the leniency terms, purchasers could offset potential liabilities, safeguard the deal's value, and even negotiate more favourable purchase conditions, turning what might have been a deal‑breaker into a strategic advantage.

The initial period following the creation of the CNMC's predecessor (the Comisión Nacional de la Competencia – "CNC")7 was thus marked by a flurry of antitrust investigations, particularly in the area of cartel enforcement, as Spain sought to align its practices with those of the national competition authorities acting in more mature European antitrust jurisdictions such as Germany, France, and the United Kingdom.8 This alignment was reflected in a series of major cases, including the 2015 automobile manufacturers' cartel decision, which remains one of the largest antitrust fines in Spanish history, with 18 car makers sanctioned a total of €131.4 million for exchanging sensitive pricing data.9 This decision, upheld in substantial part by the Spanish Supreme Court (Tribunal Supremo) in 2021 and 2022, reinforced the CNMC's ability to prosecute information exchange cartels in highly concentrated industries.10

From 2016 onwards, Spain's competition enforcement landscape underwent a gradual yet unmistakable shift. The early dynamism that had characterised the CNC and, in its first years, the CNMC, began to wane. Although 2015 marked a record high year in cartel enforcement, with 15 decisions imposing fines totalling over €500 million, subsequent years witnessed a steady decline in both the volume of investigations and the total amount of sanctions. In 2016, the CNMC issued nine cartel decisions, imposing €218 million in fines (around €150 million net after leniency reductions). Yet by 2019, while the aggregate sum of fines (€471 million) suggested robust activity, this figure was heavily skewed by a single major railway cartel decision.11 The broader trend pointed towards fewer investigations and a narrowing enforcement focus.12

This decline cannot be explained solely by market dynamics. Judicial scrutiny brought renewed attention to what, in retrospect, may have been overly ambitious early enforcement efforts, prompting a period of institutional reflection. From 2016 onwards, Spain's National Appeals Court (Audiencia Nacional) and, later, the Tribunal Supremo, began overturning several landmark cartel decisions, citing insufficient evidence and procedural flaws. The annulment of the cement cartel fines—totalling €29 million—in 2021 exemplified this pattern.14 Other major reversals followed, including the dairy cartel,15 where €80.6 million in fines were struck down due to procedural irregularities.

Far from representing mere setbacks, these judicial rulings underscore the indispensable role of the courts in aligning competition enforcement with the constitutional guarantees afforded to individuals and firms under investigation. Article 24 of the Spanish Constitution secures the right to effective judicial protection and due process, while Article 117 affirms judicial independence and the supremacy of the law. By subjecting decisions of the CNMC to rigorous appellate scrutiny, the judiciary acts as a necessary check on administrative power, ensuring that sanctions are grounded in robust evidence and procedurally sound frameworks. Moreover, Article 103's directive that public agencies adhere strictly to the principles of legality, efficacy, and impartiality obliges enforcement authorities like the CNMC to exercise their mandate with discipline and restraint. These constitutional provisions do not merely provide abstract protections; they operate as structural guarantees that uphold both the integrity of antitrust enforcement and the rights of those subject to it.

Seen in this light, each judicial reversal is not simply a correction of error but a reaffirmation of the legal standards that must underpin any durable enforcement system. They prompt the CNMC to recalibrate its approach—enhancing investigative rigor, elevating evidentiary thresholds, and fortifying procedural guarantees—ultimately forcing the agency to adopt a more cautious and constitutionally grounded path forward.

The past five years have seen this caution crystallise into a sustained moderation of enforcement. Although some significant fines were still imposed—such as the €127 million railway signalling cartel in 2021,16 the €204 million construction cartel in 2022,17 and the high-profile €194 million sanction against big U.S. tech companies in 202318—these cases have been exceptional rather than indicative of broader investigative vigour. Outside of these headline cases, the number of dawn raids, new investigations, and sector-wide inquiries has remained relatively low. Moreover, the growing success rate of appeals has compounded this moderation: by late 2024, nearly one-third of cartel sanctions imposed since 2014 had been fully annulled or substantially reduced by the Spanish courts.19

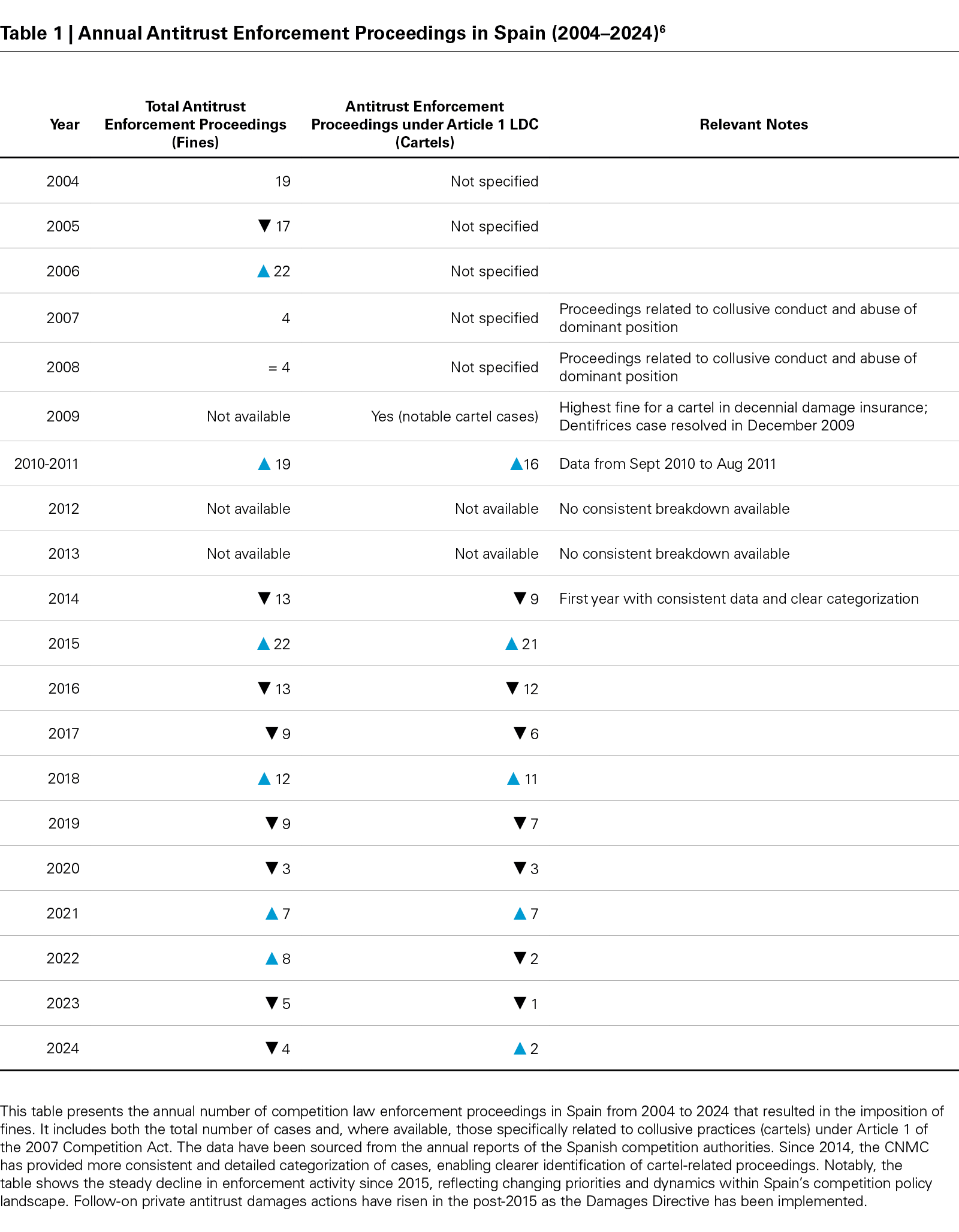

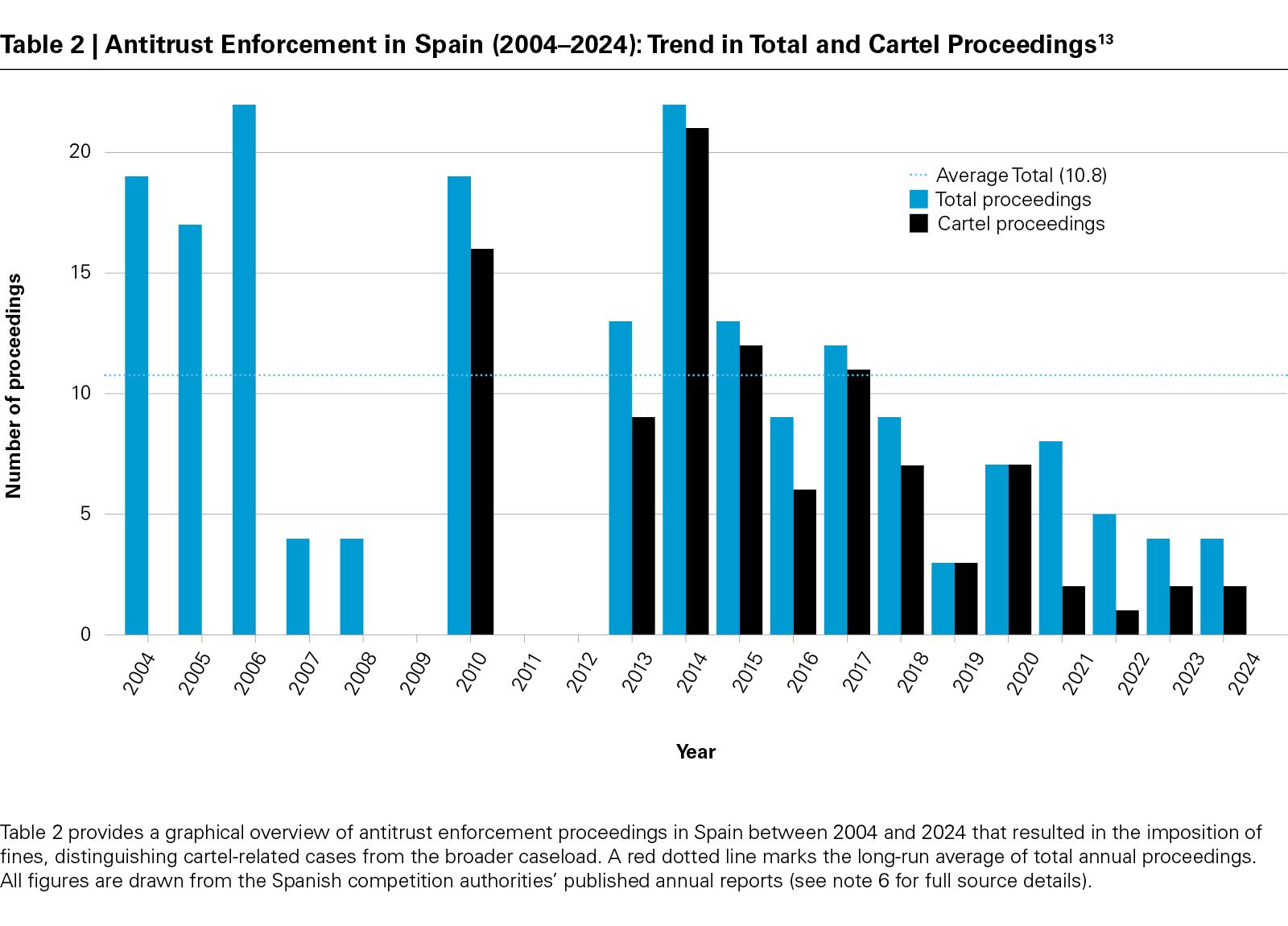

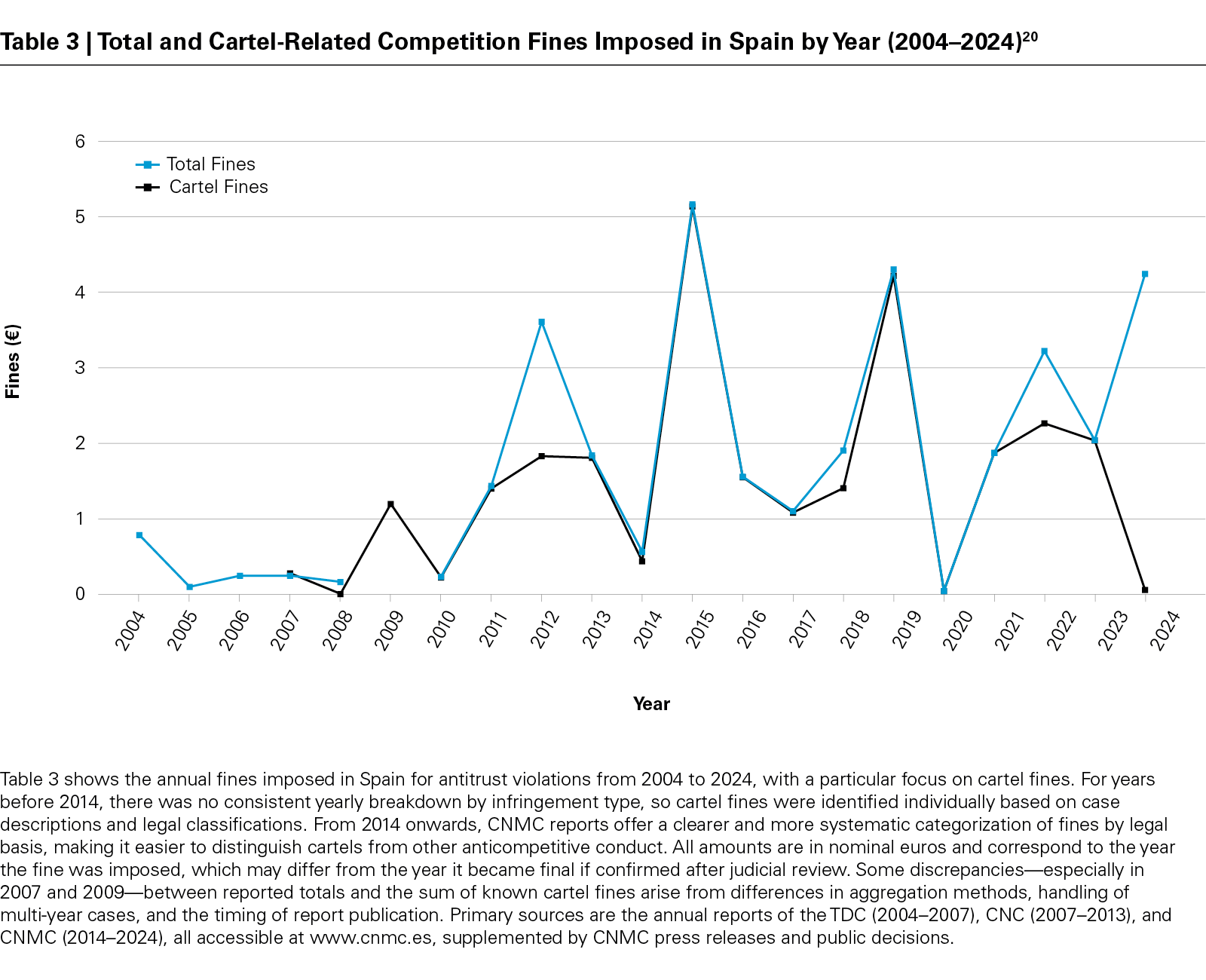

The evidence reveals a sharp and sustained decline in enforcement intensity since 2016, accelerating over the past five years. As shown in Tables 1 and 2, this trend is visible in the reduced number of investigations initiated by the Spanish competition authority. Table 3 complements this picture by illustrating the steep fall in the volume of fines imposed, particularly in cartel cases. While there is a marked drop since the peak in 2015, the decline in fines is less pronounced than the fall in the number of proceedings, suggesting that the CNMC has shifted its focus towards fewer cases involving higher penalties per company. This shift underscores a change in enforcement style: from broad-based deterrence to more selective, concentrated action. Although the CNMC remains a visible player in Europe's competition landscape, its recent trajectory stands in stark contrast to the cartel-busting ambition and drive of the CNC's formative years: what was once a bold and proactive cartel enforcement regime has become more cautious and subdued.

A deeper dive into CNMC case law and enforcement patterns further illuminates the drivers behind this shift. Between 2014 and 2019, the CNMC sanctioned approximately 55 percent of its competition cases as cartels, dismantling 32 cartels and imposing over €970 million in fines (cartel-related sanctions represented the bulk of its €1.2 billion total in that period)21. During those years, the CNMC built a reputation for aggressive cartel enforcement, pursuing horizontal conduct across a range of sectors and asserting a strong deterrent posture. Since then, however, its enforcement style has grown more restrained, with a noticeable reduction in both the breadth of investigations and the frequency of infringement decisions. This trend has become particularly visible in the 2020–2024 period. In 2020, the CNMC imposed total fines of just €7.4 million, a dramatic fall from the €282 million imposed in 2019. Although 2021 saw a temporary uptick with six cartel decisions, the trend quickly resumed: only two cases were concluded in 2022, three in 2023, and just two in 2024. Over the same period, the overall number of sanctions remained well below the levels seen in the authority's earlier years. Even so, cumulative fines across 2020–2022 still amounted to approximately €515 million, reflecting a continued focus on a small number of high-impact cases. These figures confirm a strategic shift: the CNMC is now pursuing fewer investigations, but focusing on greater evidentiary robustness and higher per-case penalties. While it remains to be seen whether this latter batch of decisions will withstand judicial scrutiny, the new approach suggests that the CNMC is assimilating lessons from prior rulings and refining its enforcement practices to enhance their resilience on appeal. Moreover, the decline in case numbers is sharper than the decline in total fines, suggesting that the Spanish antitrust watchdog has reoriented its enforcement model to preserve deterrence through intensity rather than volume.

The €413 million penalty on a global online travel platform in 2024 for imposing parity clauses and restricting price discounts on Spanish hotels22 exemplifies the CNMC's recalibrated enforcement focus. The CNMC is now targeting large platforms, crafting behavioral remedies, and favouring sectors where a single anti-competitive practice can reverberate across a broad network of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which represent 99.8 percent of all Spanish firms and employ over 62 percent of the workforce.23 In a country where SMEs are dominant economic actors, abuses by dominant digital intermediaries can have amplified ripple effects across businesses, micro‑enterprises, and regional ecosystems.

Against this backdrop, the CNMC appears to be refocusing scarce investigative resources toward cases with systemic reach, such as dominance abuse in digital markets or high‑profile mergers, rather than continuing resource-intensive cartel sweeps that may yield smaller returns. Yet, this strategic emphasis carries a risk: by focusing on marquee digital platforms and high‑value merger reviews, the CNMC is neglecting more discreet—but no less damaging—cartels operating within the domestic economy. Collusive schemes in industries such as construction materials, local transport services, or agrifood supply chains often involve smaller firms that fly under the radar, yet their coördinated price‑fixing ultimately burdens Spanish consumers and businesses alike. Going forward, achieving true systemic deterrence will require the CNMC to guard against these blind spots in the "economy proper," where cartel conduct by lesser-known actors can impose tangible costs on households and SMEs across Spain.

Explaining the Decline in Cartel Enforcement: A Confluence of Legal, Economic, and Institutional Factors

The decline in CNMC cartel enforcement is the product of multiple, interwoven factors. Foremost among these is the collapse in leniency applications—a development that has affected all European jurisdictions but is especially severe in Spain (over the period 2015-2021, the number of leniency applications fell by 58 percent across OECD countries, and by 80 percent in Spain).24 The adoption of Directive 2014/104/EU on antitrust damages actions (the "Damages Directive"),25 transposed into Spanish law in 2017, radically changed the incentives for companies to apply for leniency. Whereas leniency previously offered immunity from public fines with relatively modest reputational and litigation risks, post-Damages Directive leniency applicants faced near-certain exposure to substantial private damages claims—an uncertainty compounded by the national laws governing such claims and the moral hazard risk that inflated damages claims suppress amnesty applications—often pursued through mass litigation or by professional claimants.26

The Spanish courts have been inundated with follow-on litigation, notably arising from the European trucks cartel and the Spanish automotive cartels, creating an environment where the benefits of leniency are often outweighed by the costs of private enforcement.27

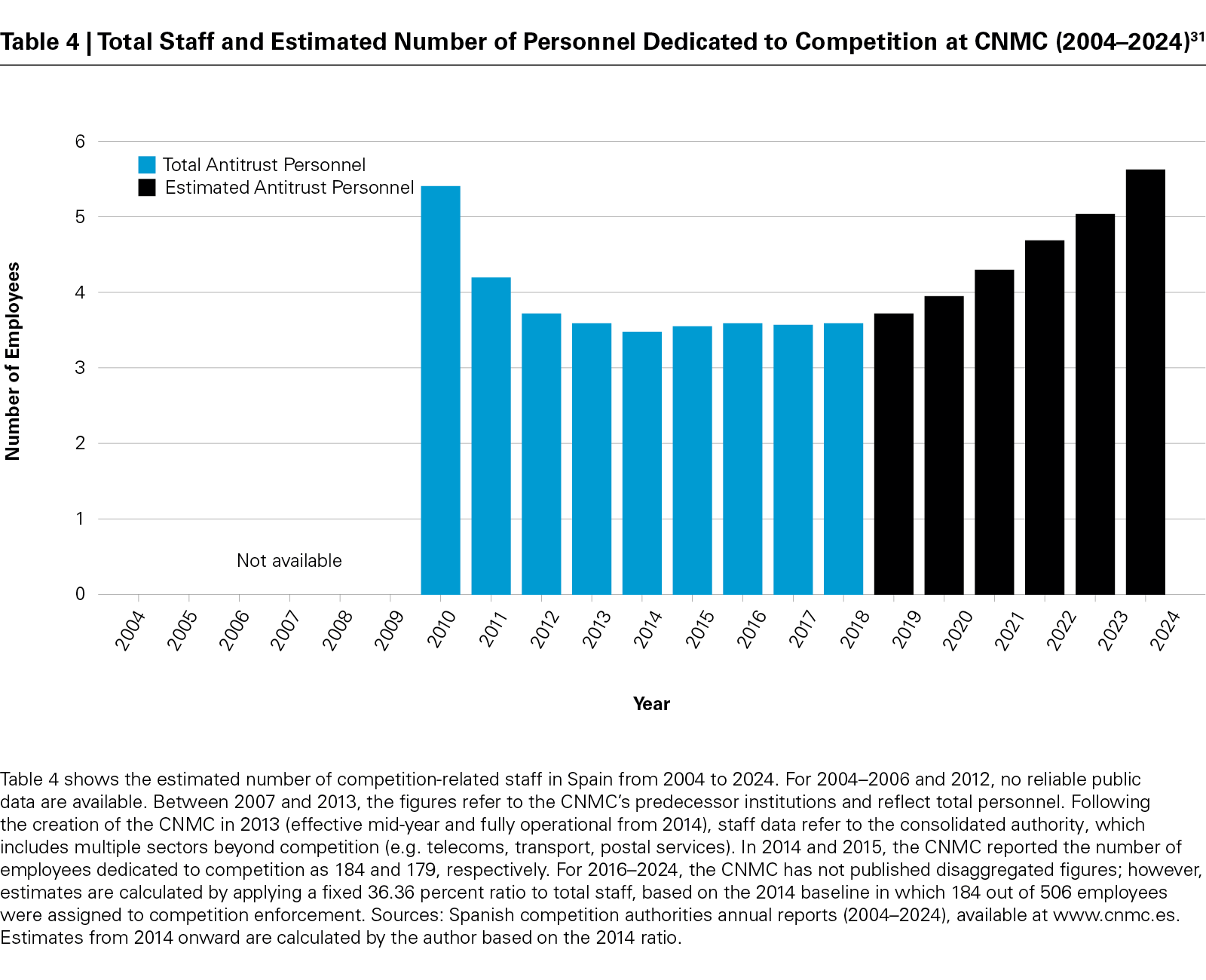

Moreover, institutional and resource constraints have compounded the fall‑off in substantive cartel investigations. Since 2018, the CNMC's investigative staff has remained largely static despite a marked increase in the complexity and volume of digital‑economy cases, reducing its bandwidth for time‑intensive dawn raids and cartel analyses (see table 4 below).28 Spain's transposition of the ECN+ Directive in 2019,29 while endowing the CNMC with stronger search and information‑gathering powers, lacked the commensurate budgetary and training commitments required to develop in‑house expertise on data‑rich sectors such as online platforms and algorithm‑driven markets. This institutional squeeze has coincided with a strategic reorientation towards regulatory oversight—particularly under the EU's Digital Single Market agenda—which, while laudable, has drawn scarce enforcement resources away from anti‑cartel work.30 Consequently, the CNMC is caught between heightened private‑damages exposure and constrained public‑enforcement capacity, a dual pressure that risks entrenching impunity for sophisticated cartelists unless bolstered by renewed political will and significant investment in specialised competition officers.

As advanced in the previous section, judicial scrutiny has further dampened the CNMC's cartel enforcement appetite. Empirical analysis confirms that 95.5 percent of fines imposed by the Spanish competition authorities between 2004 and 2015 were challenged in court. These antitrust fines generated an unparalleled level of litigation, reflected in the volume and diversity of appeals—often against both final and interim decisions—underscoring the role of due process and judicial review, as well as the weakness of certain government antitrust cases. While 38 percent of antitrust fines were upheld in full, 26 percent were entirely annulled by the courts and 36 percent had their amounts reduced. Most annulments were based on substantive grounds. Out of the total fines imposed during this period (€1.697 billion), less than half (€738 million) remained after judicial review.32

A series of high-profile annulments by the Spanish courts has underscored the challenges the CNMC faces in meeting evidentiary standards.33 The courts have demanded robust, contemporaneous evidence of collusion, invalidating CNMC decisions where circumstantial or economic evidence alone was deemed insufficient.

Aside from the higher standard of evidence, one of the most persistent issues is poor case management timelines. As noted by several legal experts,34 the growing number of cases that expire before reaching a final decision calls into question not so much the regulator's will but the actual effectiveness of the national enforcement system—suggesting an agency stretched too thin and perhaps overly ambitious. When deadlines lapse and cases vanish—not for lack of evidence but due to administrative delay or inertia—the message sent to the market ceases to be a deterrent and loses its impact. Taken together, these factors have not only eroded the credibility of past enforcement but have also introduced greater caution into future investigations.

Comparative Analysis: Spain in the EU Context

This heightened judicial exactitude reflects a broader trend within European competition jurisprudence emphasizing the protection of defendants' procedural rights and evidentiary rigour. Spanish courts have increasingly aligned with the standards set by the Court of Justice of the European Union, particularly in demanding direct proof or incontrovertible indications of concerted practices.35 Consequently, the CNMC faces a double challenge: the need to gather increasingly granular evidence in markets often characterised by covert collusion and sophisticated concealment tactics, and to do so under intense judicial scrutiny that raises the bar for admissible proof and case management. This environment has encouraged the CNMC to prioritise cases with clear documentary or testimonial evidence, potentially at the expense of more novel or digital-era cartels where evidence is harder to obtain but the harm significant. The cumulative effect is a cautious, risk-averse enforcement culture that may inadvertently reduce deterrence and allow complex cartels to persist undetected.

Spain's decline in cartel enforcement mirrors a broader downward spiral at the EU level—total fines imposed by the European Commission in 2023 fell to their lowest since at least 2005.36 Yet Spain's drop is even steeper: from a peak of €471 million in 2019 to just €5.7 million in 2024, coupled with a sharp fall in the number of new investigations.37 This dual-track contraction suggests a more pronounced structural shift, driven not only by limited enforcement capacity, but also by a strategic refocus toward other priorities.

Meanwhile, the European Union's approach to uncovering cartels is gradually pivoting from public enforcement to private litigation. Although the 2014 Damages Directive sparked a surge of follow‑on actions for damages across Member States38, without stronger incentives, leniency applications have fallen sharply, undermining the primary source of cartel intelligence.39 This decline in cartel decisions today will inevitably constrain the pipeline for follow-on damages actions tomorrow. The enforcement gap thus intensifies over time, weakening deterrence, depriving victims of redress, and limiting the ability of courts to play their complementary role in the European antitrust ecosystem.

Further compounding this dynamic is the evolving complexity of cartel behaviour in digital and platform markets, where traditional tools of detection—such as leniency applications and dawn raids—are less effective. Sophisticated algorithms can facilitate tacit collusion without direct communications, making evidence collection and proving anticompetitive coördination inherently more challenging. This technological frontier demands that enforcement agencies significantly enhance their data analytics capabilities and inter-agency coöperation, both domestically and across the EU, to keep pace with cartel innovation.

The 'Brava' programme launched by the CNMC,40 represents a strategic attempt to respond to these challenges. It is a specialised initiative designed to strengthen the agency's capacity in digital forensics and advanced data analysis. Brava relies on machine learning and big data techniques, primarily trained on datasets drawn from public tenders within Spain. While this focus provides valuable insights into a critical segment of the Spanish economy (i.e., public tenders), questions remain about the programme's effectiveness beyond this narrow scope. This is because Brava's ability to detect and investigate complex cartel schemes in the broader, more opaque private sector—especially in rapidly evolving digital markets—has yet to be demonstrated.

Rethinking the Future of Cartel Enforcement

Revitalising cartel enforcement requires a comprehensive recalibration of incentives and procedural tools. While the CNMC has already taken significant steps in this direction, including the revitalisation of its Economic Intelligence Unit41 and the development and implementation of the Brava programme, these efforts should be seen as only an initial step toward effectively detecting anticompetitive practices in an increasingly complex environment. Further reforms will be essential to restore the effectiveness of cartel enforcement.

One promising avenue is to enhance the legal protection of leniency applicants from follow-on damages claims. Yet, while leniency has proven effective in uncovering major conspiracies, over‑emphasis on immunity can risk undermining broader enforcement goals. Specifically, extensive protections for leniency applicants may diminish their accountability and shift the burden of enforcement disproportionately onto litigating defendants.

At the European level, the interplay between public leniency and private damages claims warrants a nuanced reassessment. While the Damages Directive has bolstered victims' rights, it also creates tension with leniency incentives by exposing confessor firms to substantial follow‑on litigation. Landmark rulings such as Courage Ltd v. Crehan42 and Manfredi43 affirm the principle of full compensation, but leave unresolved how to balance that right against the public interest in effective cartel detection. Any harmonisation effort should therefore focus on narrowly tailored adjustments that preserve the incentives for first-in whistleblowers while preventing opportunistic use of leniency. Crucially, such reforms must be designed to enhance, not weaken, the legitimacy and efficacy of the overall enforcement architecture.

On the national procedural front, creating a long-awaited settlement mechanism could also prove highly beneficial.44 A clear, flexible and transparent settlement framework allowing for significant discounts in exchange for early admissions of liability would not only streamline case resolution and reduce litigation costs, but also reinforce deterrence by increasing the number of concluded cases.

More specifically, a formal settlement procedure serves both legal and economic objectives. From a legal perspective, it preserves judicial resources and respects parties' due process rights by providing a consensual pathway to resolution. Economically, it attenuates the well-documented inefficiencies of protracted administrative and judicial proceedings. The seminal work of Lucian Arye Bebchuk on asymmetric information and settlement bargaining illustrates how negotiated outcomes can improve overall welfare.45 By offering discounted fines, the Spanish lawmakers would furnish the CNMC with a powerful fourfold advantage: fostering early coöperation by investigated firms, improving the ex ante detection of cartels, reducing legal uncertainty for defendants, and ultimately ameliorating the overall deterrent effect of enforcement.

Establishing a robust and transparent settlement mechanism would represent a pivotal reform in national antitrust procedure, aligning domestic enforcement with well-established approaches in the United States and the European Union. Beyond streamlining the use of public and private resources, such a system would strengthen the broader framework of deterrence, promoting a more competitive market environment to the benefit of consumers and businesses alike.46

Finally, Spain's cartel enforcement priorities must evolve to meet the demands of a changing economy. Digital platforms, sustainability-driven coöperation, and hybrid forms of collusion between public and private actors are reshaping the antitrust landscape, posing novel questions that defy traditional investigative approaches. Navigating these frontiers will require not only new tools, but also renewed institutional resolve.

Conclusion

The story of antitrust enforcement in Spain over the past two decades is one of early ambition followed by a slow but steady retreat. Landmark cartel decisions once showcased the CNMC's technical capability and resolve, but systemic headwinds—chief among them the collapse of leniency incentives, judicial skepticism, and persistent budgetary constraints—have gradually sapped its momentum. Comparative data suggest this is part of a wider European malaise, but Spain's descent has been particularly pronounced. Unless the tide is turned—through legislative reform, procedural innovation, and a rekindling of institutional purpose—the deterrent effect of competition law may start to weaken, leaving collusive conduct increasingly unchecked.

Confronting this challenge demands more than procedural adjustments; it calls for a comprehensive reckoning with the structural and political forces that have weakened the authority's hand. The decline in enforcement reflects not just legal or technical limitations, but shifting institutional priorities, as well as an increasing tilt toward regulatory supervision at the expense of competition oversight, compounded by erratic financial support and governance frameworks that lack long-term vision. Restoring the CNMC's capacity requires reinforcing its independence, ensuring stable funding, and giving it the tools to plan strategically across political cycles.

At the national level, lawmakers should act within their procedural margin to strengthen the antitrust enforcement framework. Introducing a long-overdue settlement mechanism—clear, flexible, and capable of offering meaningful discounts in exchange for settlement admissions—would accelerate case resolution, reduce litigation costs, and increase the number of completed cases. Already adopted in many peer jurisdictions, such a mechanism would have an immediate and visible impact on enforcement efficiency and deterrence. Crucially, it would also help reduce the CNMC's low batting average in the Spanish courts by allowing it to focus litigation resources on fewer, more robustly contested matters.

For its part, the CNMC need not—and should not—wait for legislative change. It has already taken promising steps, including the revamping of its Economic Intelligence Unit and the launch of the Brava detection programme. But these efforts must be deepened and refocused with a clear and sustained emphasis on cartel-busting. Strategic use of intelligence tools, greater cross-border and cross-sector coöperation, and the internalisation of innovation as a core pillar of enforcement must become permanent features of the CNMC's operating model. This is essential to tackle increasingly complex forms of collusion; from algorithmic coördination and data-driven exclusion to hybrid public-private conspiracies in procurement markets. Restoring the centrality of cartel enforcement will be critical to rebuilding deterrence and reaffirming the CNMC's role as a credible enforcer; whether the CNMC can rise to this challenge will shape the future of Spanish competition law. Much will depend on its ability to balance innovation with credibility, and ambition with consistency. The years ahead will tell whether this moment marks a passing phase, or the beginning of a genuine renewal.

Ultimately, revitalising cartel enforcement will not hinge on any single legislative fix or institutional adjustment. What is needed is a broader shift in mindset: a shared commitment to view competition policy not as a procedural formality, but as a vital tool for safeguarding economic fairness, market integrity, and consumer welfare. In Spain, restoring that vision will require sustained political support, long-term investment in enforcement capacity, and a clear reaffirmation of the CNMC's role as a guardian of open markets. The success of this effort will not only shape the future relevance of the CNMC itself but also serve as a litmus test for the strength and credibility of Spain's legal and economic order.

1 Ley 15/2007, de 3 de julio, de Defensa de la Competencia.

2 European Commission Notice on Immunity from fines and reduction of fines in cartel cases (2006/C 298/11).

3 Sherman Act § 1, 15 U.S.C. § 1; U.S. DOJ Antitrust Division Leniency Policy.

4 In Spain, between 2010—the year the first leniency applications were received—and 2022, the CNMC issued 86 cartel decisions, 44 of which (51 percent) were based on leniency applications (this figure includes eight decisions that originated from evidence of other infringements uncovered during inspections prompted by a leniency application). See CNMC (2022), "Contribution from Spain to the Latin American and Caribbean Competition Forum – Session I: Strengthening incentives for leniency agreements".

5 More recently, however, the growing threat of substantial follow-on damages claims has added a new layer of deterrence. This evolving shift in incentives is now a critical feature of the Spanish antitrust enforcement landscape and will be examined further in the main body of this article.

6 This table presents the annual number of competition law enforcement proceedings in Spain from 2004 to 2024 that resulted in the imposition of fines. It includes both the total number of cases and, where available, those specifically related to collusive practices (cartels) under Article 1 of the 2007 Competition Act. The data have been sourced from the annual reports of the Spanish competition authorities. Since 2014, the CNMC has provided more consistent and detailed categorization of cases, enabling clearer identification of cartel-related proceedings. Notably, the table shows the steady decline in enforcement activity since 2015, reflecting changing priorities and dynamics within Spain's competition policy landscape. Follow-on private antitrust damages actions have risen in the post-2015 as the Damages Directive has been implemented.

7 Established under the 2007 Competition Act and operational since September 2007, the CNC was created as an autonomous authority to strengthen Spain's competition enforcement framework, consolidating the functions of the former Competition Defence Service (Servicio de Defensa de la Competencia – SDC) and the Competition Defence Tribunal (Tribunal de Defensa de la Competencia – TDC). In 2013, the CNC was replaced by the CNMC, pursuant to Law 3/2013 of 4 June, which merged several sectoral regulators and the competition authority into a single body.

8 By 2008, Spanish lawyers described the CNC as "much more aggressive in its investigation of alleged cartels", initiating numerous cartel cases and conducting dawn raids, mirroring the approaches of mature enforcers such as Germany and France (see "EU, Competition & Public Law Report 2009: A constant in a world turned upside down", Iberian Lawyer, published in September 2009).

9 See CNMC Case No. S/0482/13 - Fabricantes de automóviles.

10 In the interest of full disclosure, the author served as lead counsel for one of the undertakings fined by the CNMC.

11 See CNMC Case No. S/DC/0598/16 - Electrificación y Electromecánica Ferroviarias, where the CNMC fined 15 companies and 14 executives a total of €118 million and €666,000 respectively, for unlawfully colluding in public tenders launched by ADIF (the Spanish Railway Infrastructure Administrator) for railway infrastructure projects involving electrification and electromechanical systems on both conventional and high-speed rail lines.

12 The pace of CNMC enforcement in 2024 continues to decline, with only 13 sanctioning decisions issued—compared to 32 cases initiated ten years ago by the now-defunct CNC.

13 Table 2 provides a graphical overview of antitrust enforcement proceedings in Spain between 2004 and 2024 that resulted in the imposition of fines, distinguishing cartel‑related cases from the broader caseload. A red dotted line marks the long‑run average of total annual proceedings. All figures are drawn from the Spanish competition authorities' published annual reports (see note 6 for full source details).

14 The Spanish Supreme Court overturned the fine imposed by the CNMC in Case S/0525/14 – Cementos on 24 cement and concrete companies, including Cementos Portland Valderribas SA, Betón Catalán SA, and Betonalia SL, for alleged anticompetitive practices. The fine was annulled due to insufficient evidence proving the existence of a cartel and market-sharing agreements between 1999 and 2014.

15 See CNMC Case No. S/0425/12 - Industrias Lácteas 2.

16 See CNMC Case No. S/DC/0614/17 - Seguridad y Comunicaciones Ferroviarias.

17 See CNMC Case No. S/0021/20 - Obra Civil 2.

18 See CNMC Case No. S/0013/21 - Brandgating.

19 "La justicia anula una de cada tres sanciones de la CNMC a empresas por cárteles" Cinco Días, 2 December 2024.

20 Table 3 shows the annual fines imposed in Spain for antitrust violations from 2004 to 2024, with a particular focus on cartel fines. For years before 2014, there was no consistent yearly breakdown by infringement type, so cartel fines were identified individually based on case descriptions and legal classifications. From 2014 onwards, CNMC reports offer a clearer and more systematic categorization of fines by legal basis, making it easier to distinguish cartels from other anticompetitive conduct. All amounts are in nominal euros and correspond to the year the fine was imposed, which may differ from the year it became final if confirmed after judicial review. Some discrepancies—especially in 2007 and 2009—between reported totals and the sum of known cartel fines arise from differences in aggregation methods, handling of multi-year cases, and the timing of report publication. Primary sources are the annual reports of the TDC (2004–2007), CNC (2007–2013), and CNMC (2014–2024), all accessible at www.cnmc.es, supplemented by CNMC press releases and public decisions.

21 See article by the then President of the CNMC, José María Marín Quemada, published in Global Competition Review on 12 July 2019.

22 See CNMC Case No. S/0005/21.

23 See OECD Capital Market Review of Spain (2024), published on 5 December 2024.

24 "The Future of Effective Leniency Programmes - Advancing Detection and Deterrence of Cartels", OECD Competition Policy Roundtable Background Note, 2023. See also information included in the CNMC annual reports.

25 Directive 2014/104/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 November 2014 on certain rules governing actions for damages under national law for infringements of the competition law provisions of the Member States and of the European Union.

26 "Leniency inflation, the Damages Directive, and the decrease in cartel cases", Catarina Marvao and Giancarlo Spagnolo, CEPRS, 9 Mar 2024.

27 "The 'Boom' in Private Enforcement of Competition Law from a Spanish Perspective: Importance of Economic Side of Private Enforcement Litigation", Esther de Félix Parrondo, Maria Perez Carrillo, Covadonga Garralda and Raquel Nuñez, Mondaq, 23 February 2023.

28 "Lack of resources holding CNMC back, agency head says", Francesca McClimont, Global Competition Review, 27 February 2025.

29 Directive (EU) 2019/1 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2018 to empower the competition authorities of the Member States to be more effective enforcers and to ensure the proper functioning of the internal market.

30 On 24 January 2024, the Spanish Ministry for Digital Transformation and Public Services adopted a decision to appoint the CNMC as the national Digital Services Coördinator. The CNMC will be responsible for supervising the application of the Digital Services Act (DSA). As such, the CNMC has the responsibility of supervising, investigating and potentially sanctioning service providers established in Spain that fall within the scope of the DSA. Further, the CNMC is tasked with certifying so-called trusted flaggers, which are entities trusted with identifying illegal content themselves.

31 Table 4 shows the estimated number of competition-related staff in Spain from 2004 to 2024. For 2004–2006 and 2012, no reliable public data are available. Between 2007 and 2013, the figures refer to the CNMC's predecessor institutions and reflect total personnel. Following the creation of the CNMC in 2013 (effective mid-year and fully operational from 2014), staff data refer to the consolidated authority, which includes multiple sectors beyond competition (e.g. telecoms, transport, postal services). In 2014 and 2015, the CNMC reported the number of employees dedicated to competition as 184 and 179, respectively. For 2016–2024, the CNMC has not published disaggregated figures; however, estimates are calculated by applying a fixed 36.36 percent ratio to total staff, based on the 2014 baseline in which 184 out of 506 employees were assigned to competition enforcement. Sources: Spanish competition authorities annual reports (2004–2024), available at www.cnmc.es. Estimates from 2014 onward are calculated by the author based on the 2014 ratio.

32 "La revisión judicial de las resoluciones de la autoridad nacional de competencia (ANC) en España (2004-2021)", Professor Francisco Marcos, El Almacén del Derecho, 13 December 2023.

33 See, inter alia, Audiencia Nacional, judgments of 20, 21 and 23 June 2022, Prosegur and Loomis, appeals no 581/2016, 22/2017, and 21/2017. See also "Spain: The Audiencia Nacional annuls, due to insufficient evidence, a decision of the Spanish competition authority fining two security companies and their managers for having participated in the sharing of the cash-in-transit and cash-handling market (Prosegur / Loomis)", Concurrences, 23 June 2022.

34 Including Professor Francisco Marcos (see article published in La Voz de Galicia titled "La Justicia anula a Competencia más de 140 millones en multas por lentitud", 30 June 2025).

35 See, e.g., Case C‑8/08, T‑Mobile Netherlands BV and Others v Raad van bestuur van de Nederlandse Mededingingsautoriteit, EU:C:2009:343, paras 35–41; Case C‑74/14, Eturas and Others, EU:C:2016:42, paras 33–45; Case C‑49/92 P, Commission v Anic Partecipazioni SpA, EU:C:1999:356, paras 115–123; and Case T‑415/08, FLS Plast A/S v Commission (PVC II), EU:T:2013:207, paras 293–298. These judgments confirm that while concertation can be proved by a consistent body of indirect evidence, the CJEU requires "incontrovertible indicia" where no direct proof is available and will accept presumptions only where supported by context and not rebutted.

36 DG Comp levied €88.9 million in fines across four decisions, which is way down on its record in recent years, having issued €188.6 million in 2022, €1.75 billion across 10 decisions in 2021, €288.1 million in 2020, €1.48 billion across five decisions in 2019 and €800.7 million across four decisions in 2018 (see Global Competition Review, Analysis of the European Union's Directorate-General for Competition, 30 September 2024).

37 Enforcement by the CNMC continues to weaken in 2024, with only 13 sanctioning decisions issued, less than half the 32 cases initiated by the CNC in 2014. Although CNMC-imposed fines in the competition sphere totaled €425 million, this amount was largely driven by a single record sanction exceeding €400 million against a global online travel platform for abuse of dominance; fines imposed elsewhere reached a new low of just €25 million (see CNMC 2024 Annual Report).

38 By the end of 2020, at least 299 cartel damages actions had been decided in 14 EU Member States, up from roughly 50 cases in early 2014—a six‑fold increase in follow‑on private litigation linked to cartel infringements (see "Private Enforcement Of EU Competition Law: Recent Developments", an article published in Modaq.com on 13 October 2023 by Frédéric Louis, Anne Vallery, Cormac O'Daly and Édouard Bruc.

39 In the absence of robust leniency rewards or enhanced legal certainty, firms increasingly opt to remain silent, leaving authorities dependent on resource‑intensive ex officio investigations or sporadic whistle‑blower tips, mechanisms that, without comprehensive protection and encouragement, risk failing to capture the full spectrum of illicit collusive conduct.

40 Brava (Bid Rigging Algorithm for Vigilance in Antitrust) is a CNMC model that, using artificial intelligence tools, classifies the bids submitted by companies in a tender as potentially collusive or competitive. The project was developed by staff from the CNMC's Economic Intelligence Unit, with support from the IT Sub-Directorate, following a prior proof of concept carried out by the company awarded a public contract. The key to Brava lies in its algorithm based on machine learning, which uses the Spanish public procurement database as its source and has enabled the creation of a pioneering tool worldwide among competition authorities.

41 The CNMC's Economic Intelligence Unit has boosted its investigative activity from one ex officio inquiry in 2023 to four in 2024 (see CNMC's 2024 Annual Report).

42 Judgment of the Court of Justice of the European Union of 20 September 2001, Courage Ltd v Bernard Crehan and Bernard Crehan v Courage Ltd and Others (C-453/99 - Courage and Crehan).

43 Joined Cases C-295/04 to C-298/04 - Vincenzo Manfredi and Others v Lloyd Adriatico Assicurazioni SpA and Others.

44 Spain's competition framework, as of mid‑2025, remains distinctive in what it lacks: there is no statutory settlement mechanism comparable to the European Commission's settlement procedure for cartel cases (see Commission Notice on the conduct of settlement procedures in view of the adoption of Decisions pursuant to Article 7 and Article 23 of Council Regulation (EC) No 1/2003 in cartel cases.) Across the EU, parties acknowledging their involvement in cartel conduct may engage in settlement discussions to expedite resolution, accept facts and legal classification, and secure a 10 percent fine reduction. This process allows the Commission to achieve faster outcomes and reduce litigation burden. In contrast, Spain's national law, as enforced by the CNMC, does not provide any formal avenue for such settlements.

45 L.A. Bebchuk — Litigation and settlement under imperfect information. Rand Journal of Economics, 1984.

46 The EU experience suggests that procedural clarity and limited incentives, when combined, can deliver measurable enforcement gains without eroding defendants' rights. Empirical analysis of European Commission cartel cases decided between 2000 and 2014 demonstrates the practical impact of these limited incentives combined with procedural clarity. After the Settlement Notice came into force, the median duration of the second phase of cartel proceedings—from the Statement of Objections to the adoption of a final decision—contracted by more than twelve months, while the overall timeline from initiation to decision likewise shortened substantively (see Discussion Paper No. 15-064, The Settlement Procedure in EC Cartel Cases: An Empirical Assessment, K. Hüschelrath and U. Laitenberger, Zentrum für Europäische Wirtchaftsforschung – ZEW).

White & Case means the international legal practice comprising White & Case LLP, a New York State registered limited liability partnership, White & Case LLP, a limited liability partnership incorporated under English law and all other affiliated partnerships, companies and entities.

This article is prepared for the general information of interested persons. It is not, and does not attempt to be, comprehensive in nature. Due to the general nature of its content, it should not be regarded as legal advice.

© 2025 White & Case LLP

View full image: Table 1 | Annual Antitrust Enforcement Proceedings in Spain (2004–2024)

View full image: Table 1 | Annual Antitrust Enforcement Proceedings in Spain (2004–2024)

Table 2 | Antitrust Enforcement in Spain (2004–2024): Trend in Total and Cartel Proceedings (PDF)

Table 2 | Antitrust Enforcement in Spain (2004–2024): Trend in Total and Cartel Proceedings (PDF)

Table 3 | Total and Cartel-Related Competition Fines Imposed in Spain by Year (2004–2024) (PDF)

Table 3 | Total and Cartel-Related Competition Fines Imposed in Spain by Year (2004–2024) (PDF)

Table 4 | Total Staff and Estimated Number of Personnel Dedicated to Competition at CNMC (2004–2024) (PDF)

Table 4 | Total Staff and Estimated Number of Personnel Dedicated to Competition at CNMC (2004–2024) (PDF)