The lack of food security is a persistent issue facing parts of Africa. The number of Africans who are undernourished has been increasing, even as the global hunger trends show modest improvements in other regions. In 2022, nearly 19.7 percent of the African population was undernourished, an increase of 4.6 percentage points since 2010, according to a report by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Thus, in many parts of Africa, food insecurity is chronic, affecting hundreds of millions.

Further, the urgency to act is heightened by a growing population, with the United Nations estimating growth from 1.34 billion in 2020 to 2.8 billion by 2050. Hence, the crucial question is: can food production for the growing population in Africa be increased in sustainable manner amid mounting environmental pressures?

Africa, the second-largest continent in the world (according to the World Population Review), has all the pre-requisites for overcoming food insecurity: vast arable land, a youthful and entrepreneurial population, and abundant natural resources. Yet, numerous obstacles remain.

In this article, we explore some of the challenges to food security, highlight projects that are using innovative financing to tackle food insecurity and consider how it can be widely adopted.

Barriers to food security

Climate change implications

With temperatures increasing by 2 to 4℃ (according to the International Livestock Research Institute), climate change poses a massive threat to agriculture in many parts of Africa. A diet of many Africans is centred around wheat, maize, sorghum and millet. Thus, as the United Nations reports, a temperature increase by 2 to 3℃ could reduce the chance of crops surviving in sub-Saharan Africa by 10 to 20 percent, while anything above 3℃ would make agricultural sustainability nearly impossible. The situation is worse in southern Africa because of its erratic rainfall and longer droughts, which undermine crop cycles. Meanwhile, farmers often cultivate marginal lands and deal with population pressures, further depleting soil quality. Additionally, the Sahel, once dotted with fertile fields, is steadily being overtaken each year by advancing sands.

Insufficient agricultural investment

Significant investment is key to combating the effects of climate change and financing the development of sustainable agricultural practices. However, smallholders, who make up the majority of Africa's farmers, struggle to access credit. Furthermore, agriculture and investments in nature-based solutions are not typical asset classes for project finance lenders, which presents another hurdle.

Due diligence hurdles

Another challenge is understanding the property landscape. Typically, due diligence would be conducted to verify a client's credibility, assess risks and make informed decisions before a significant transaction. However, land tenure systems are often ambiguous, with overlapping customary and statutory rights that can make the due diligence process challenging and undermine the financial viability of projects relying on land for security.

A complex legal landscape

Navigating any legal landscape is crucial to delivering a successful project. However, in many countries in Africa, the legal landscape is complex and requires deep expertise to address risks, such as inadequate legislation, currency fluctuation and political uncertainties. Overcoming these barriers requires a multi-faceted and targeted approach. This way, strong environments and reliable legal frameworks that enable African infrastructure projects to flourish can be built, allowing African countries to unlock their full potential.

Scale of investment needs

According to a report by the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, Africa's food import bill is projected to increase sharply, from US$15 billion in 2018 to US$110 billion by 2025. Global estimates, noted in a United Nations Environment Programme report, suggest that investment in nature-based solutions must triple by 2030 and quadruple by 2050 to at least US$500 to US$970 billion each year to meet international targets. Africa's share of that demand is vast.

In many African countries, the natural capital financing gap is acute; domestic public budgets alone cannot close it. Furthermore, since the current third-party funding is dominated by public and development finance institutions (DFIs), scaling the participation of private capital in projects of this kind is key.

Encouragingly, recent data show that commercial lending for impact lending in on the African continent is possible, and has been happening mainly through DFIs deploying both concessional and commercial financing schemes. To illustrate, in 2021, according to a report by the International Finance Corporation, DFIs used blended concessional finance solutions to support US$13.4 billion of private-sector projects; of that, about US$1.9 billion consisted of concessional commitments (grants, subordinated debt, guarantees) and US$5.3 billion was DFI commercial financing.

Regarding adaptation finance in Africa, a Global Center on Adaption report states that a high share of DFI funding is already in the form of commercial-rate loans (41 percent) compared to concessional loans (32 percent).

Hence, this data underscores that while concessional capital remains essential, it is still only a portion of what is being deployed—and that scaling of private and commercial finance is a key objective.

Major initiatives: Testing the financing models

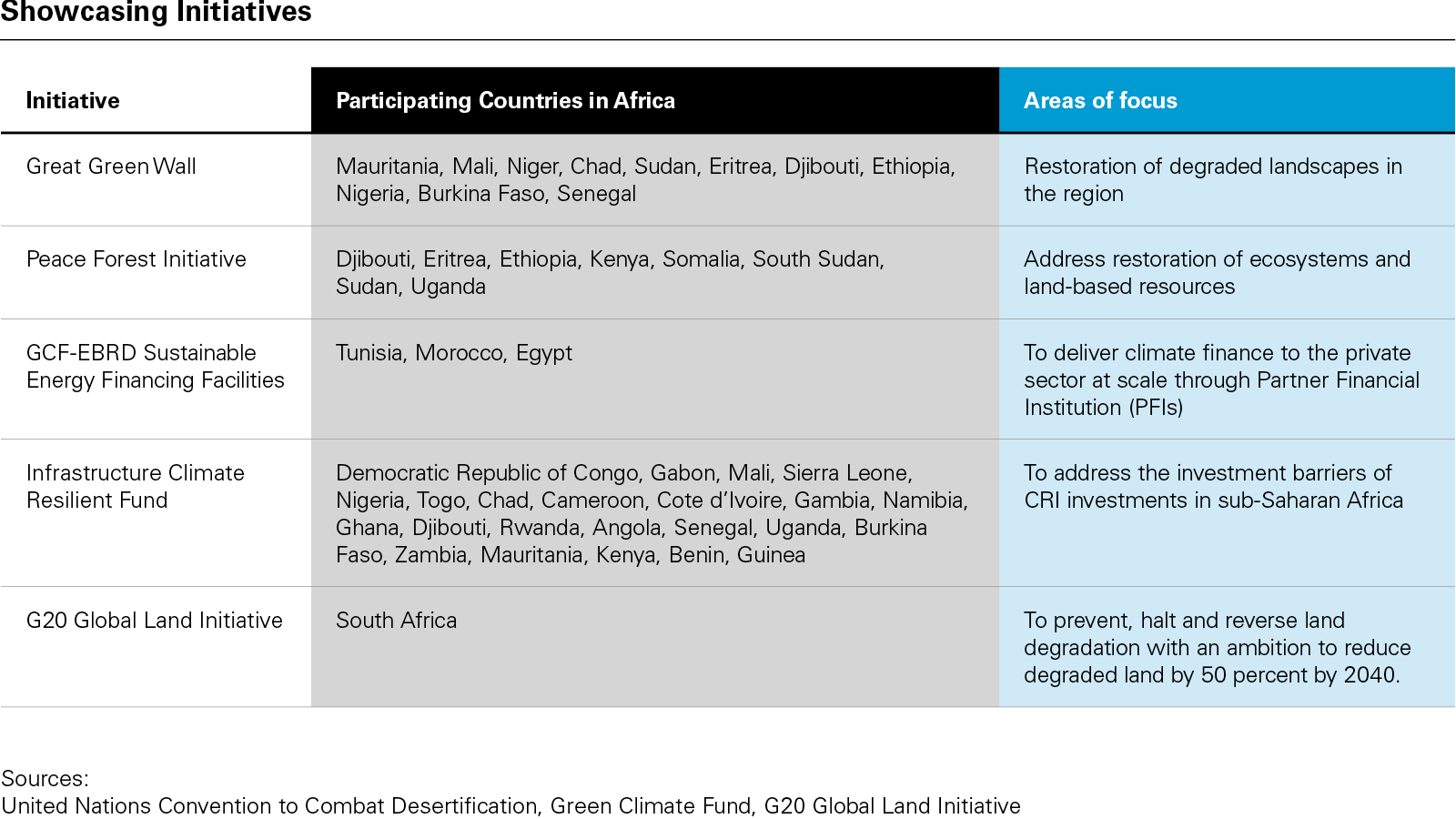

A series of flagship initiatives illustrate both the promise and the limits of financing food security and climate resilience in Africa.

Great Green Wall

The Great Green Wall (GGW) is perhaps the most ambitious initiative. A living barrier across 11 Sahelian countries, its aim is to restore 100 million hectares of degraded land, sequester 250 million tons of carbon, and create ten million green jobs by 2030. So far, nearly 18 million hectares have been rehabilitated, and 350,000 jobs have been created.

However, GGW's financing reveals its ambitious scale. More than US$19 billion has been mobilized, largely from the World Bank, African Development Bank (AfDB), Agence Française de Développement (AFD), International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), European Investment Bank (EIB) and the Green Climate Fund (GCF). Yet, another US$33 billion is required to meet the 2030 targets. Most of this funding is concessional loans and grants, though commercial banks have participated in syndicates alongside DFIs, which is a sign of a cautious but growing appetite.

Peace Forest Initiative

The Peace Forest Initiative (PFI), spearheaded by the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification, focuses on restoration in fragile and conflict-affected areas, including the Horn of Africa. The challenges of governance and security make purely commercial finance implausible. Early backers such as the AfDB and GCF provide grants and concessional capital. In the long run, scaling will require innovative structures that combine peacebuilding with environmental gains.

GCF-EBRD Sustainable Energy Financing Facilities

The GCF and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development's Sustainable Energy Financing Facilities (SEFF) partner with local financial institutions to provide climate finance to households, small and mid-sized enterprises and special purpose vehicles. With US$378 million from the GCF and more than US$1 billion in co-financing, the model uses on-lending by local banks—demonstrating how to multiply impact through existing financial ecosystems.

Infrastructure Climate Resilient Fund

The Infrastructure Climate Resilient Fund (ICRF), approved in 2023, integrates climate resilience directly into African infrastructure development. With US$253 million from the GCF and US$511 million in co-financing from the African Finance Corporation (AFC) and EIB, it embeds resilience into roads, bridges and energy systems. This is critical because without it, climate events could wipe out billions in infrastructure assets.

G20 Global Land Initiative

The G20 Global Land Initiative highlights the role of global coalitions. With Saudi Arabia pledging US$10 million annually for coral reef-related projects, it demonstrates political will but is heavily dependent on grants. For many projects in Africa, turning these pledges into blended structures that attract private investment remains a challenge.

Risks and financial viability: Why private finance hesitates

Food security requires not only global engagement but also funding to resolve. New funding models and channels are being actively developed by the global community to combat this threat. However, one key question remains: Why do commercial lenders hesitate to invest?

A seminar convened by the Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum highlighted that the main challenge for investors is the lack of bankable projects. Given that, it is becoming apparent that development cannot be driven solely by an abundance of lenders willing to fund, there must be projects, and they must be bankable.

Some of the issues attributable to a lack of bankable projects include:

- Political and currency risks may threaten any commercial transaction and make the participation of DFIs and export credit agencies (ECAs) essential.

- Regulation that falls short of international standards, forcing financial institutions to rely more on their internal standards and implement more robust due diligence and monitoring requirements that contribute to higher transactional costs.

- Legacy issues relating to the environmental, social and human rights risks that make projects challenging for the commercial lenders' compliance team to approve.

In addition, financing of nature and agricultural solutions has its own hurdles:

- Lack of diversification: To address, diversify the revenue stream from nature and apicultural financings to make investments and commercial lending more economically viable, and explore options beyond carbon credits.

- Scaling financing: To make projects impactful and meaningful, financing needs to be deployed at scale, which involves reaching out to small holdings that are often fragmented. Mechanisms will be required to attract the necessary large-scale financing. Also, financing needs to be presented in a systematic and coordinated way to individual farmers, while ensuring that smallholders comply with lender covenants.

- Due diligence: Due diligence remains a challenge because land rights are not always properly recorded, and instances of encroachment continue.

- Unique land parcels: Unlike many industrial projects, where ready-to-go solutions are possible, each land parcel and each nature reserve is different. It requires studies and bespoke solutions that work for that particular place, taking into account modern scientific data, traditional agricultural methods and tapping into the experience of people who tendered the respective land for generations.

- Lack of precedent: There is still very little precedent, although helpful templates will evolve over time.

For lenders, this complexity translates into high costs for relatively modest deal sizes.

Pathway forward

Despite these hurdles, solutions are emerging. Blended finance is one of those solutions. By layering concessional and commercial tranches, DFIs create structures where private investors can take on senior positions at a reduced risk. First-loss guarantees, political risk insurance and currency hedging can make it even more attractive for the commercial lenders.

Aggregation is another promising pathway. Instead of financing individual smallholders, funds and/or cooperatives can pool together their resources for projects that allow them to spread risk and reduce transaction costs. Then, project vehicles or specialized funds on-lend to farmers under standardized terms. This approach mirrors microfinance but at a larger, climate-focused scale.

Another notable development is the advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) tools. Traditionally, verifying land tenure, environmental compliance or project outcomes required costly field surveys. For some fragmented smallholder projects, this was prohibitive. AI has the potential to change the economics. Satellite imagery, drones and machine learning models can be used to provide the necessary assessment and monitoring data needed to deliver tailor-made solutions to each specific land parcel. They also offer the necessary comfort to lenders regarding covenant compliance in a cost-efficient manner.

Additionally, the importance of revenue diversification should not be underestimated. Projects that rely solely on carbon credits face volatility. But if revenues include timber, fruit, watershed protection payments and insurance savings, the risk profile changes. Here, partnerships with companies seeking offsets or resilient supply chains can unlock additional cash flows.

Above all, building precedents matters. Each successful structure, whether GGW syndicates or SEFF on-lending, creates a blueprint for future projects and ultimately, it lowers the uncertainty risk for future lenders. Moreover, the implementation of projects such as the GGW shows that, despite being a hurdle, financing in this sphere is possible. Also, the participation of commercial banks in the syndicate demonstrates that there is an appetite for these projects.

Key takeaways

The monumental challenge faced by many parts of Africa in resolving food security—driven by rapid population growth and accelerating environmental degradation—requires tens of billions of dollars annually in sustainable agriculture, ecosystem restoration and resilient infrastructure. Current initiatives illustrate both the promise and limitations of existing financing models, as most rely heavily on concessional and public finance. The pathway forward, however, must involve commercial lenders and private capital in greater numbers.

Blended concessional finance, backed by DFIs and ECAs, will remain essential to attract private investment. The use of AI and digital monitoring tools provides an additional lever, reducing due diligence costs and allowing projects to scale. By building robust institutions, clear legal frameworks and innovative financial models, a food security crisis can be transformed into an opportunity for sustainable development.

Ultimately, the solution will not be purely financial or technological. Rather, it requires an integrated approach, combining concessional and commercial funds, advanced data-driven monitoring and strong local engagement. It is not easy, but the potential on the African continent is substantial. If the right paths are taken, it can yield significant benefits: a food-secure climate-resilient Africa with thriving agricultural and natural ecosystems that can generate and maintain revenue for the continent's betterment.

Tomike Olukanni (Trainee Solicitor, White & Case, London) contributed to the development of this publication.

White & Case means the international legal practice comprising White & Case LLP, a New York State registered limited liability partnership, White & Case LLP, a limited liability partnership incorporated under English law and all other affiliated partnerships, companies and entities.

This article is prepared for the general information of interested persons. It is not, and does not attempt to be, comprehensive in nature. Due to the general nature of its content, it should not be regarded as legal advice.

© 2025 White & Case LLP

![Aerial View of Palm Oil Plantation [Ghana]](/sites/default/files/styles/magazine_publication_image/public/images/hero/2025/10/africa-focus-autum-2025-thought-leadership-the-european-deforestation-directive-implications-for-africas-food-security-hero.jpg?itok=YUCckZ-2)

![Wall dividing a agriculture field from above [Angola]](/sites/default/files/styles/magazine_publication_image/public/images/hero/2025/10/africa-focus-autum-2025-thought-leadership-securing-africas-future-building-resilient-food-and-energy-systems-hero.jpg?itok=rPIUhjaQ)

![Victoria Falls [Zambia]](/sites/default/files/styles/magazine_publication_image/public/images/hero/2025/10/africa-focus-autum-2025-thought-leadership-food-security-in-africa-tackling-the-water-infrastructure-crisis-through-legal-and-financial-strategies-hero.jpg?itok=nIo8RzZW)

View full image: Showcasing Initiatives

View full image: Showcasing Initiatives