Introduction

The 2025 International Arbitration Survey, entitled “The path forward: Realities and opportunities in arbitration”, investigates current trends in user preferences and perceptions, and opportunities to shape the future innovation and development of the practise of international arbitration. It explores how users of international arbitration view pressing issues such as how to tackle inefficiencies, the competing interests of confidentiality and transparency in relation to disputes involving public interest issues, trends in enforcement of awards and the transformative potential of technology.

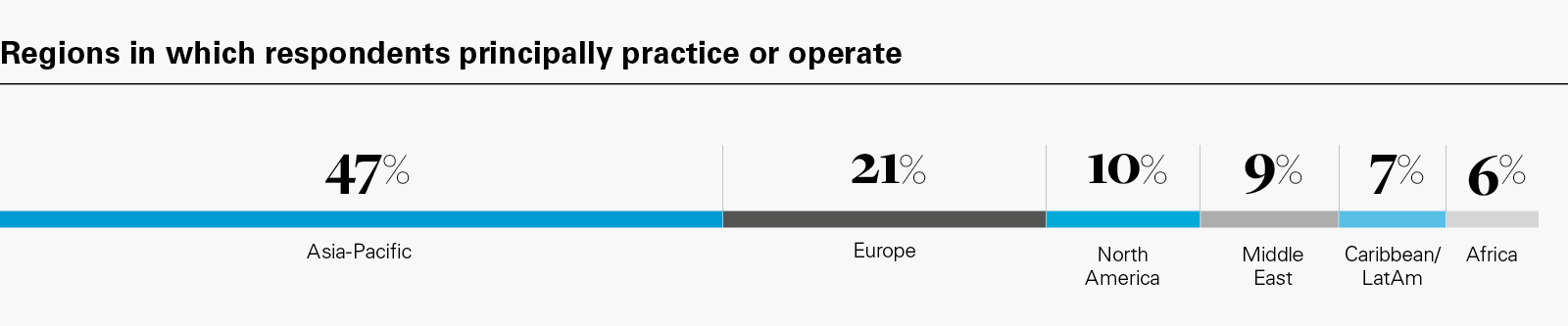

This edition saw the widest ever pool of participants (2,402 questionnaire responses received and 117 interviews conducted), almost double the number who participated in our previous survey. Views were sought from a diverse pool of participants, including in-house counsel from both public and private sectors, arbitrators, private practitioners, representatives of arbitral institutions and interest groups, academics, tribunal secretaries, experts and third-party funders. The survey provides a breakdown of some results by categories of respondents, such as by their primary role or the geographic regions in which they principally practise or operate, providing unique insight into the range of views expressed by different stakeholders across the international arbitration community.

White & Case is proud once again to have partnered with the School of International Arbitration at Queen Mary, University of London. The School has produced a study that provides valuable empirical insights into what users of international arbitration want and their expectations for the future. We are confident that this survey will be welcomed by the international arbitration community.

We thank Norah Gallagher, Dr. Maria Fanou and Dr. Thomas Lehmann (White & Case Postdoctoral Research Associate) for their outstanding work, and all those who generously contributed their time and knowledge to this study.

Norah Gallagher

Director, School of International Arbitration,

Centre for Commercial Law Studies,

Queen Mary University of London

It is fascinating to see how quickly the international arbitration community moves on. It only seems like yesterday that we were conducting a survey in the middle of a global pandemic. COVID-19 did warp our perception of time yet the speed with which things have changed since is remarkable. International geopolitics has shifted significantly, resulting in an increased awareness of challenges when arbitrating a dispute when sanctions have been imposed on either party. The responses to these questions in the survey on public interest reflect the current geopolitical status. There has been a significant increased acceptance and reliance on Artificial Intelligence (“AI”). This is perhaps one of the most surprising elements of this survey. The international arbitration community expect AI use to grow rapidly in the coming years.

This is the 14th empirical survey conducted by the School of International Arbitration, Queen Mary University of London and the sixth in partnership with White & Case LLP. We are grateful for their continued support with this important empirical research. We rely entirely on the goodwill of the international arbitration community to complete the questionnaire. This is the only way we can ensure we get the most comprehensive data. This survey involved the largest number of respondents to date with over 2,400 globally. Dr. Thomas Lehmann, our White & Case Postdoctoral Research Associate at QMUL, also interviewed 117 respondents to add colour and context to the quantitative stage.

Highlights

The 2025 Survey explores a number of key international arbitration issues, including: how AI is changing the game in international arbitration, efficiency, the enforcement of arbitration awards and public interest issues (such as human rights and corporate social responsibility).

This edition saw a 97% increase in respondents from the previous survey, with 2402 questionnaire responses received and 117 interviews conducted.

White & Case made a donation to the Child Rights International Network for every completed questionnaire.

87% of respondents prefer international arbitration for resolving cross-border disputes

London top choice

London is the top choice seat overall for respondents. London and Singapore both rank among the top five seats for each of the six regions in which respondents principally practise or operate.

ICC Rules lead the way

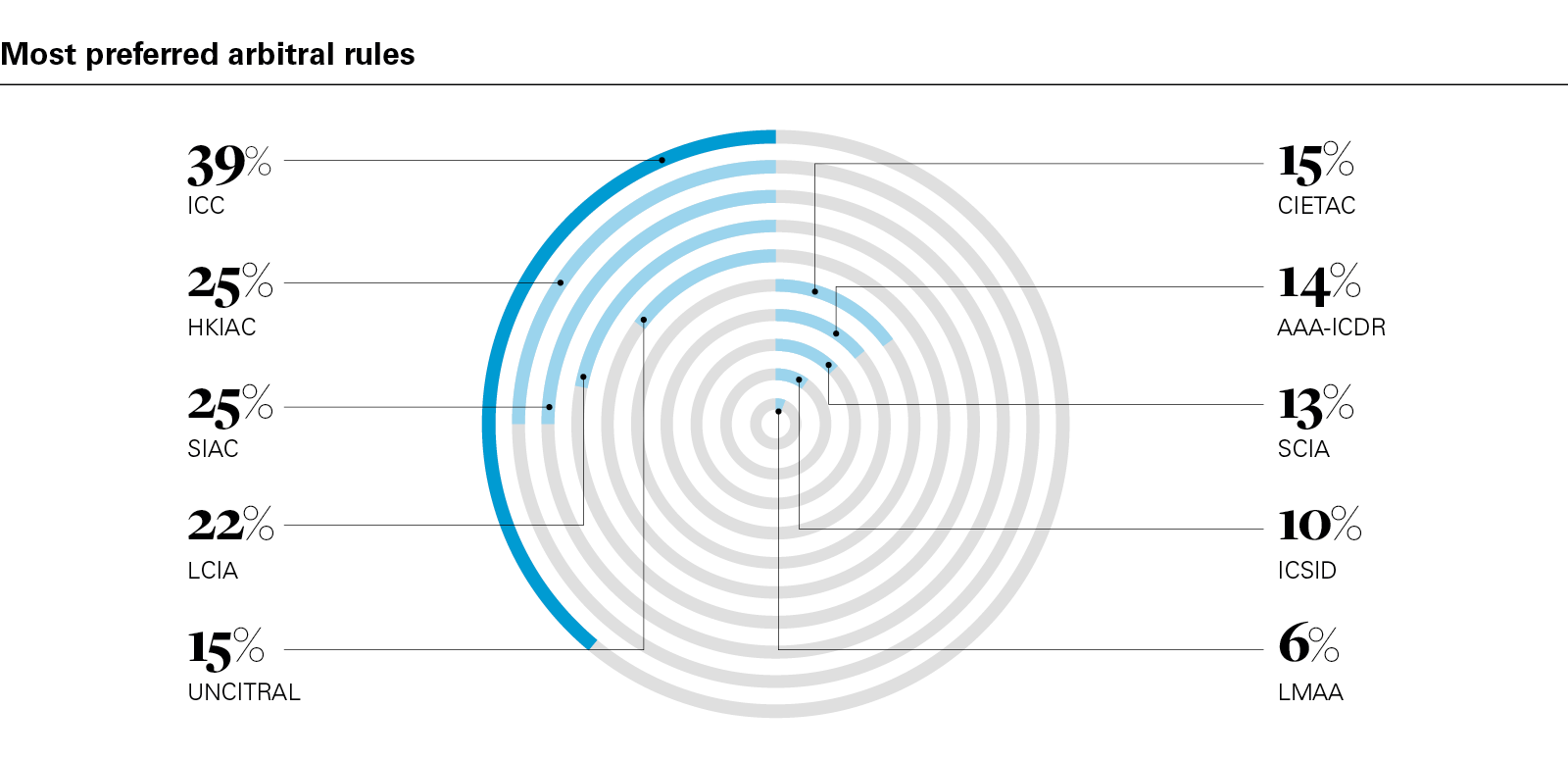

The ICC Arbitration Rules top the ranking, with 39% of all respondents including them as one of their choices, closely followed by the HKIAC Rules and the SIAC Rules (each attracting votes from 25% of respondents).

Express lane to efficiency

Both counsel and arbitrators are responsible for behaviour that negatively impacts efficiency in arbitration. Respondents called for greater proactivity and courage from both counsel and arbitrators to address this. On enforcement of awards, the majority of respondents believe annulled awards should not be enforceable.

Keeping it confidential

Respondents are conscious of the challenge of balancing confidentiality and transparency where public interest issues may arise in arbitrations. Confidentiality remains key, particularly in commercial arbitrations not involving State parties.

Public access to arbitration

90% of respondents do not favour making hearings public in commercial arbitration

59% of respondents support publishing redacted awards in ISDS case

AI as game changer

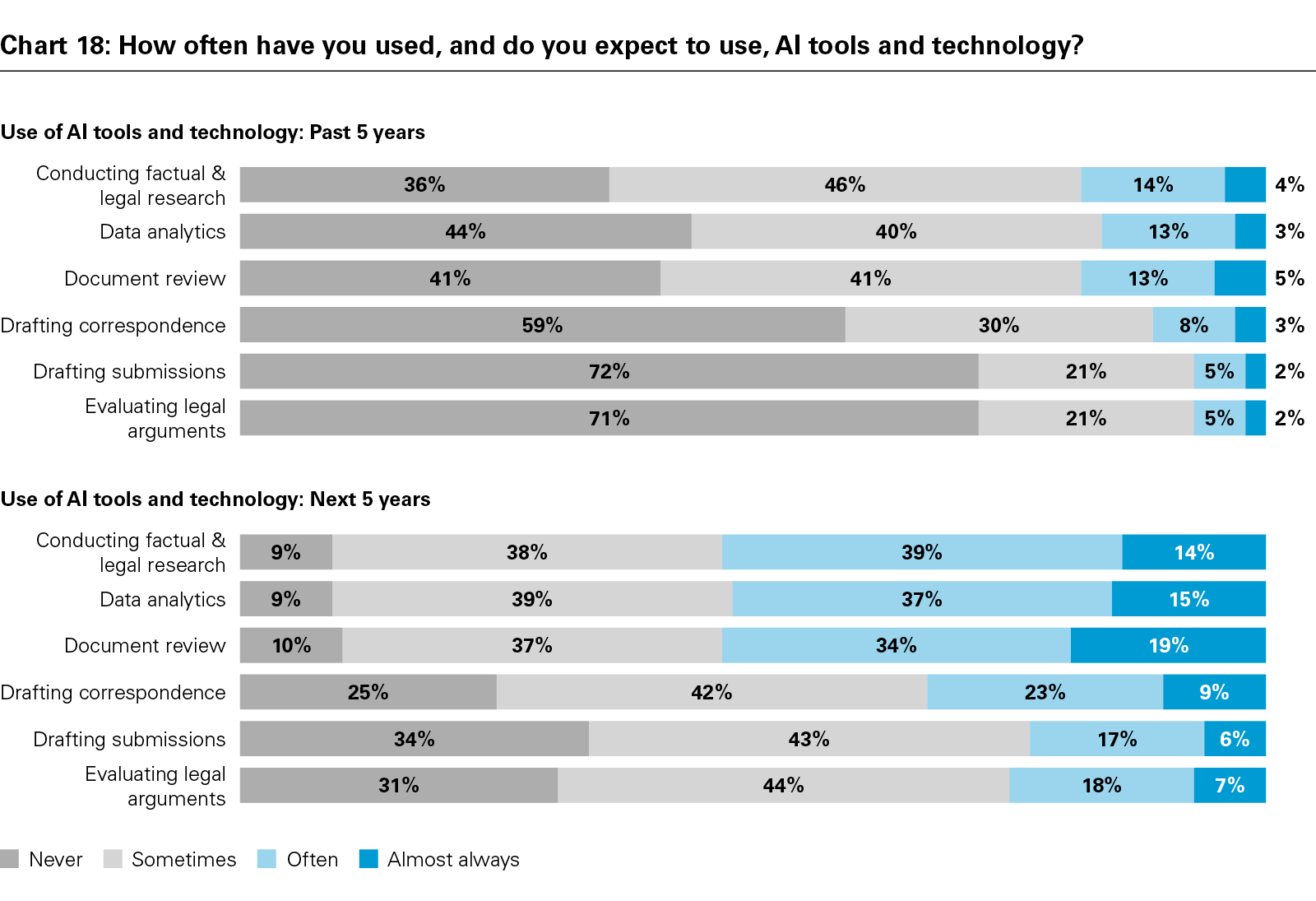

Use of AI is expected to grow significantly over the next five years, driven by the potential for efficiencies. Principal current uses of AI include factual and legal research, data analytics and document review. AI assistance in drafting and in evaluating legal arguments is also expected to increase, but there are concerns around accuracy, ethical issues, and AI's ability to handle complex legal reasoning.

AI in international arbitration

of respondents expect to use AI for research, data analytics and document review

say saving time is the biggest driver for use of AI

say the main obstacle is the risk of AI errors and bias

Chapters

Executive Summary

The 2025 International Arbitration Survey questionnaire was completed by 2,402 respondents, nearly doubling the response rate from the previous survey held in 2021. This is the largest and most representative pool of participants yet.

Experiences and preferences

- An overwhelming majority (87%) of respondents continue to choose international arbitration to resolve cross-border disputes, either as a standalone mechanism (39%) or with Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) (48%). There has been a slight decline in preference for arbitration combined with ADR compared to previous surveys.

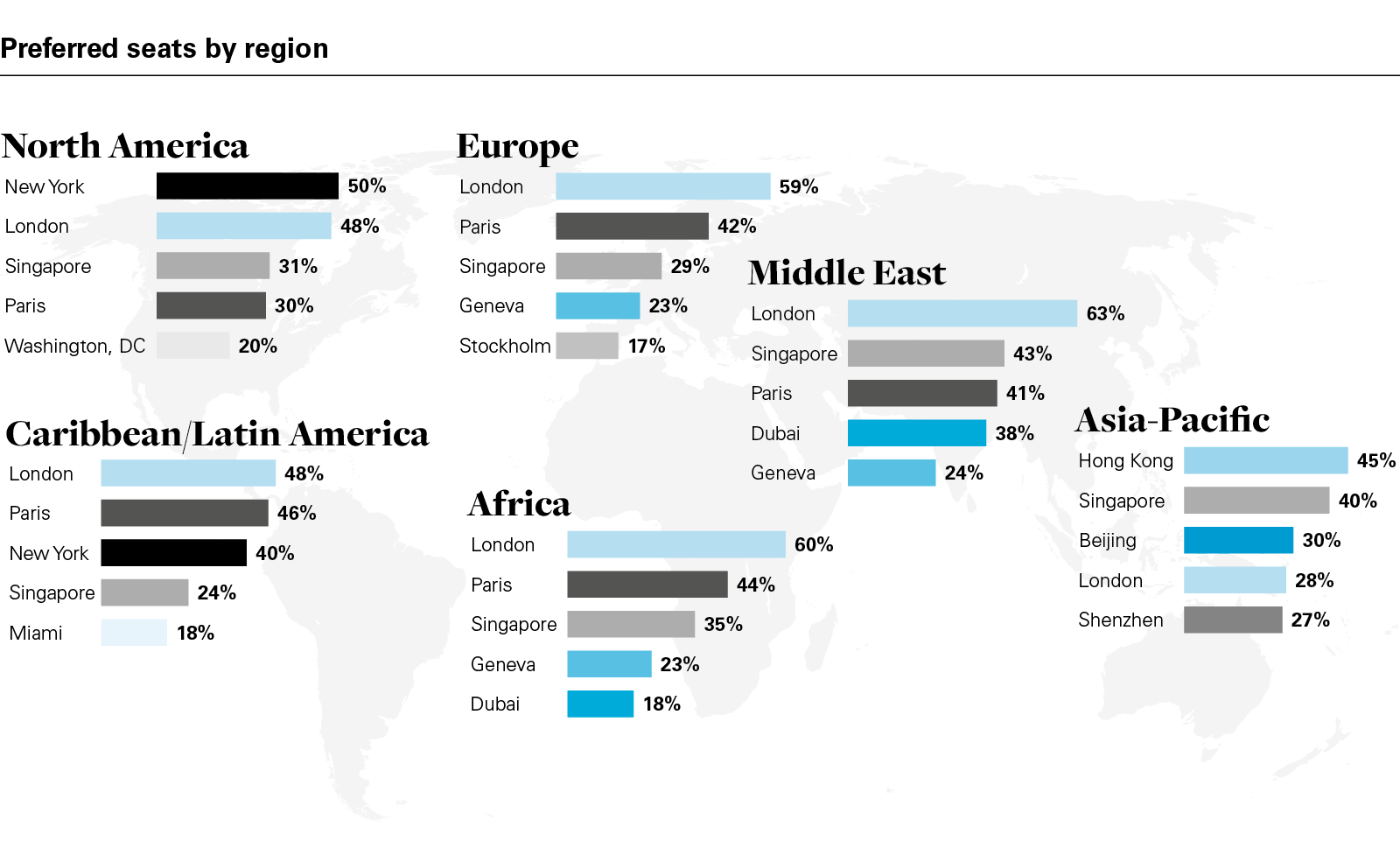

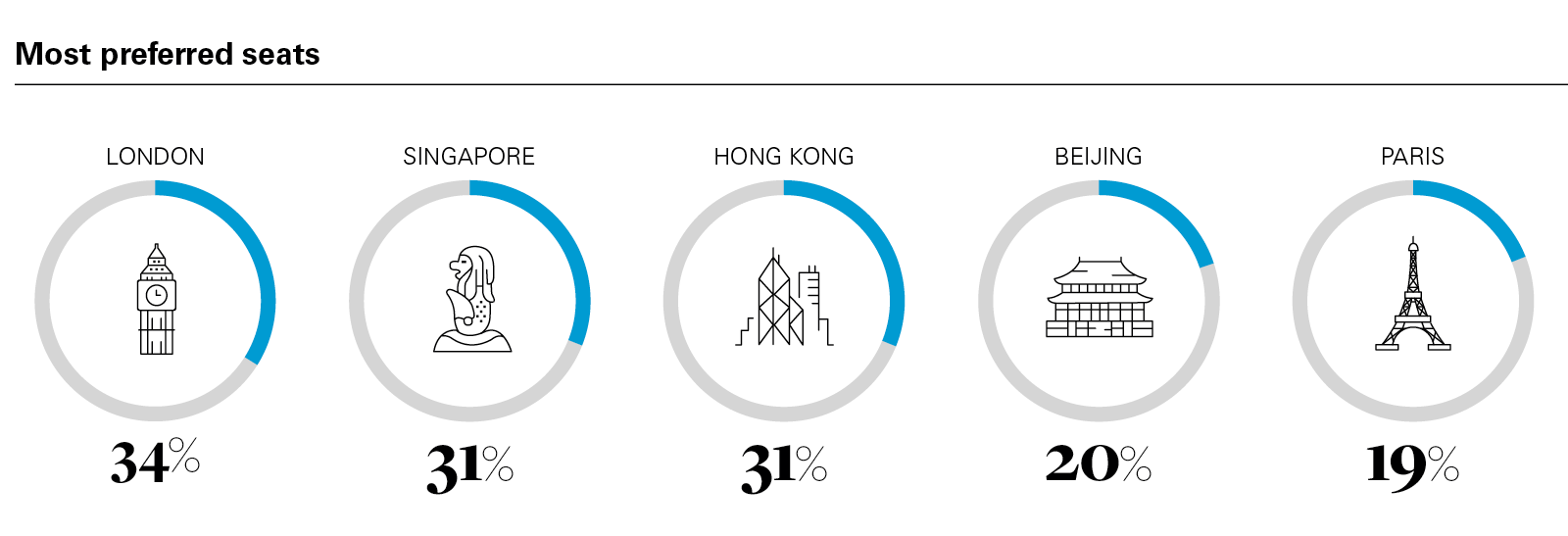

- The five most preferred seats for arbitration are London, Singapore, Hong Kong, Beijing and Paris. London and Singapore rank among the top five seats for each of the six regions in which respondents principally practise or operate.

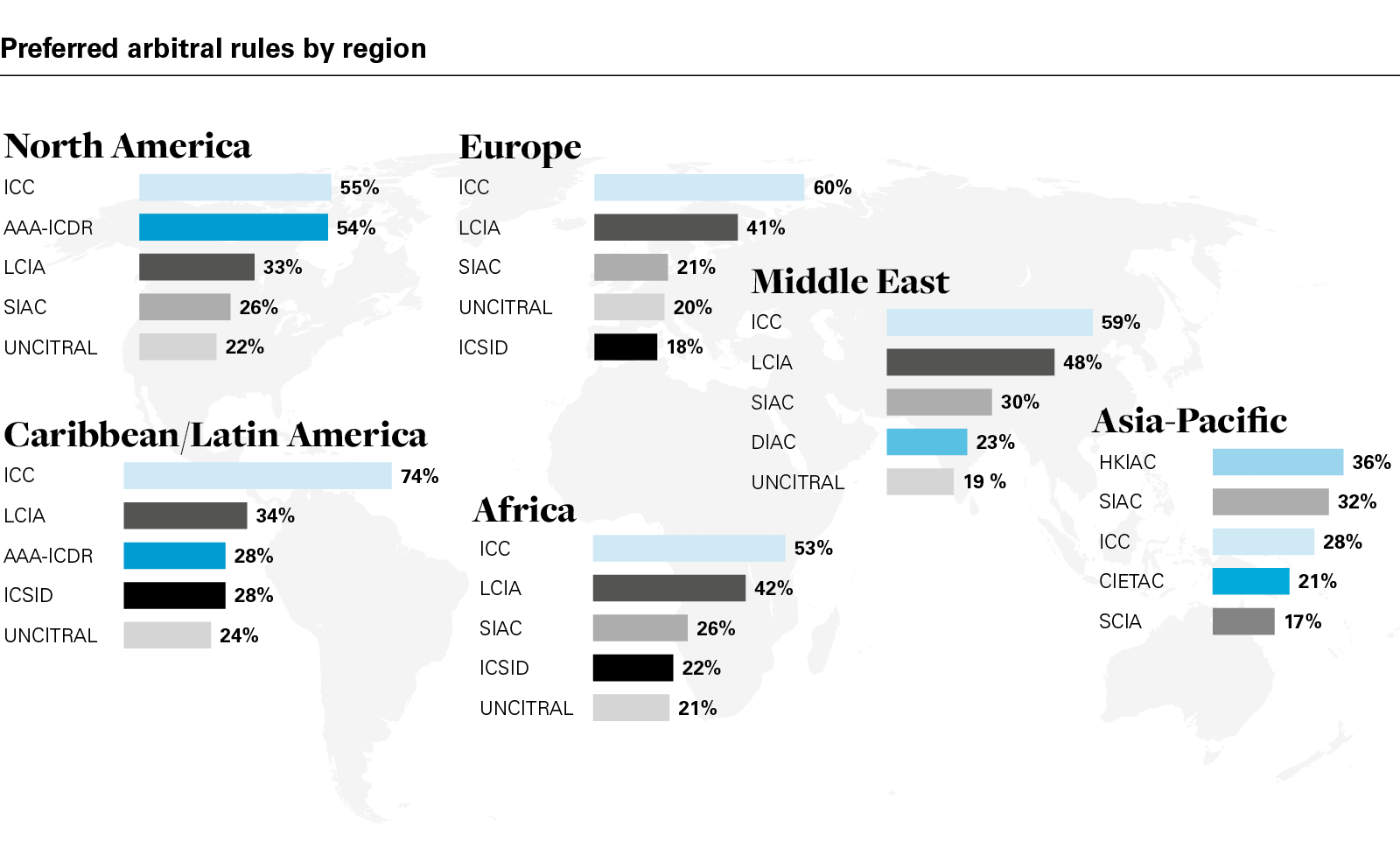

- The five most preferred sets of arbitral rules are the ICC Rules, HKIAC Rules, SIAC Rules, LCIA Rules and UNCITRAL Rules. The ICC Rules are in the top three choices for each of the six regions.

- Geopolitical or economic sanctions impact arbitration proceedings in various ways: 30% of respondents chose a different arbitral seat; 27% faced administrative and payment challenges; 25% experienced difficulty finding counsel or arbitrators able to participate, raising concerns about access to justice.

Enforcement

- Award debtors generally voluntarily comply with arbitral awards, particularly when they are private parties rather than States or state entities. Unsurprisingly, the highest level of voluntary compliance is seen with consent awards, with only 8% of respondents reporting they are ‘never’ or ‘rarely’ complied with.

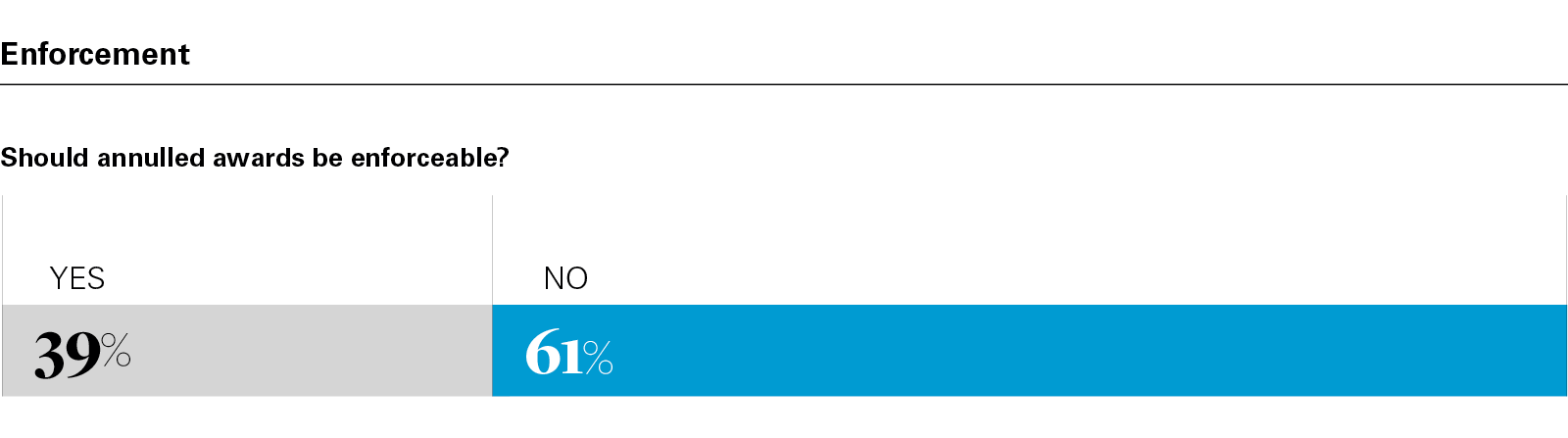

- The majority of respondents (61%) consider that awards annulled at the seat should not be enforceable in other jurisdictions. Still, many suggest it might be advisable to allow enforcement of an award that was annulled.

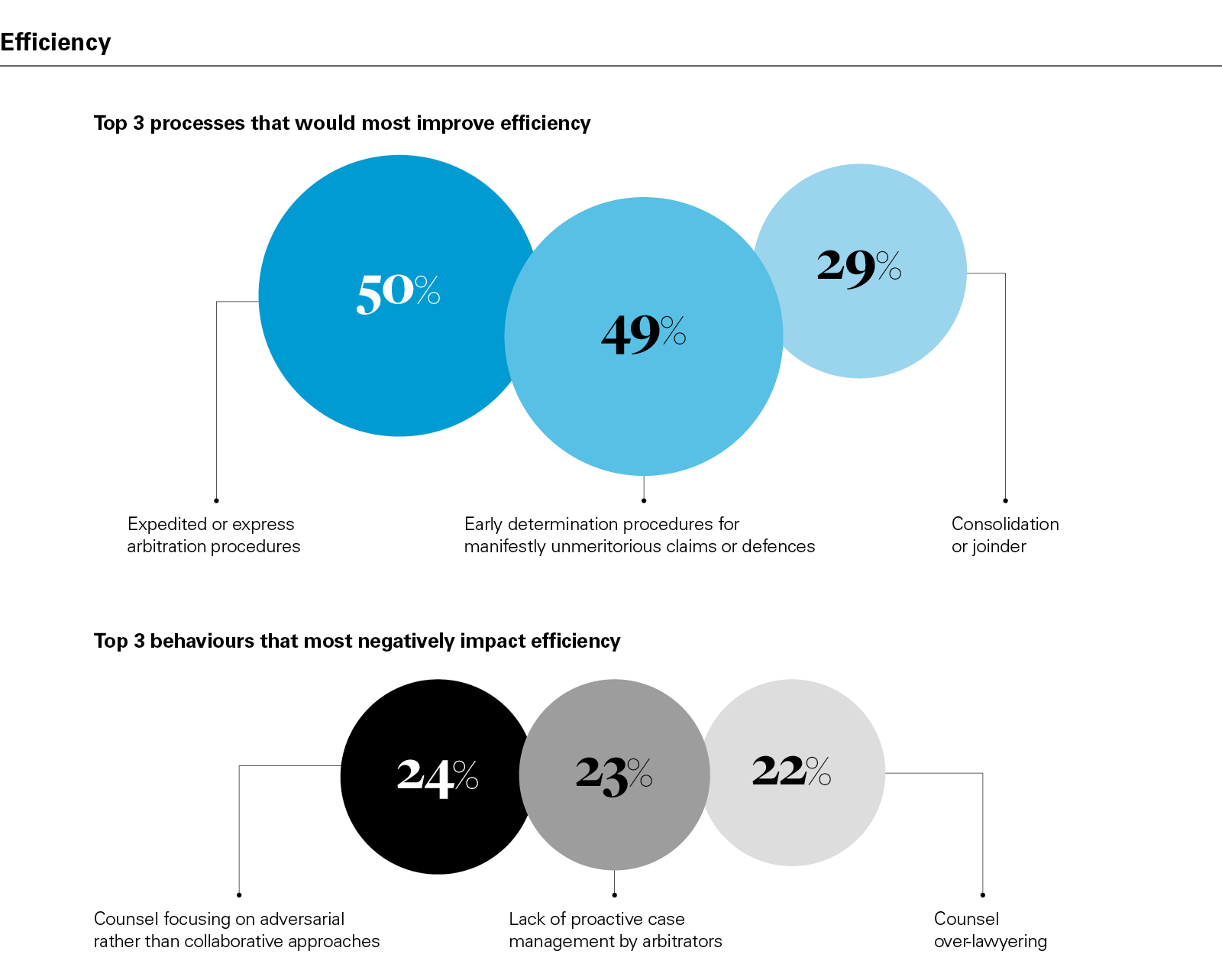

Efficiency and effectiveness

- The behaviours that most negatively impact efficiency in arbitration include adversarial approaches by counsel (24%), lack of proactive case management by arbitrators (23%) and counsel over-lawyering (22%). Respondents called for greater proactivity and courage from both counsel and arbitrators to address inefficiencies.

- The most effective mechanisms for enhancing efficiency were expedited arbitration procedures (50%) and early determination procedures for manifestly unmeritorious claims or defences (49%). While expedited procedures are particularly useful in less complex cases, their success depends on the tribunal’s readiness to make swift decisions.

- Respondents enjoyed excellent experiences with mechanisms for expediting arbitrations, such as expedited arbitration procedures embedded in arbitral rules and paper-only arbitration. Most would be willing to use them again. They also acknowledged the need to balance efficiency with procedural fairness.

- The decision to choose expedited procedural mechanisms is driven by pragmatic concerns, principally the desire to minimise costs (65%) and ensure rapid resolution (58%), particularly for disputes of lower value or complexity.

Public interest in arbitration

- Only one third of any of our respondents have encountered the various categories of public interest issues in their arbitrations. There is, however, an expectation that environmental and human rights issues will increasingly become present in both purely commercial arbitrations and disputes involving States or state entities.

- The primary advantages of international arbitration for resolving disputes involving public interest issues include the ability to select arbitrators with relevant experience or knowledge (47%) and to avoid specific legal systems or national courts (42%).

- The most significant challenges in arbitrating disputes involving public interest issues include balancing confidentiality and transparency (47%) and the lack of arbitral tribunal power over third parties (46%).

- Confidentiality of arbitration in this context can be viewed as both beneficial for delicate or reputation-sensitive disputes, and problematic for the potential to shield improper conduct of state entities from public scrutiny.

- Respondents are divided on whether international arbitration proceedings should be ‘open’ to the public. The vast majority favour maintaining confidentiality, especially in commercial arbitration. There is, however, greater support for publication of redacted awards, especially for disputes involving States or state entities.

Arbitration and AI

- Use of AI is expected to grow significantly over the next five years, driven by the potential for efficiencies. Principal current uses of AI include factual and legal research, data analytics and document review. AI assistance in drafting and in evaluating legal arguments is also expected to increase, but significant concerns persist about accuracy, ethical issues and AI’s ability to handle complex legal reasoning.

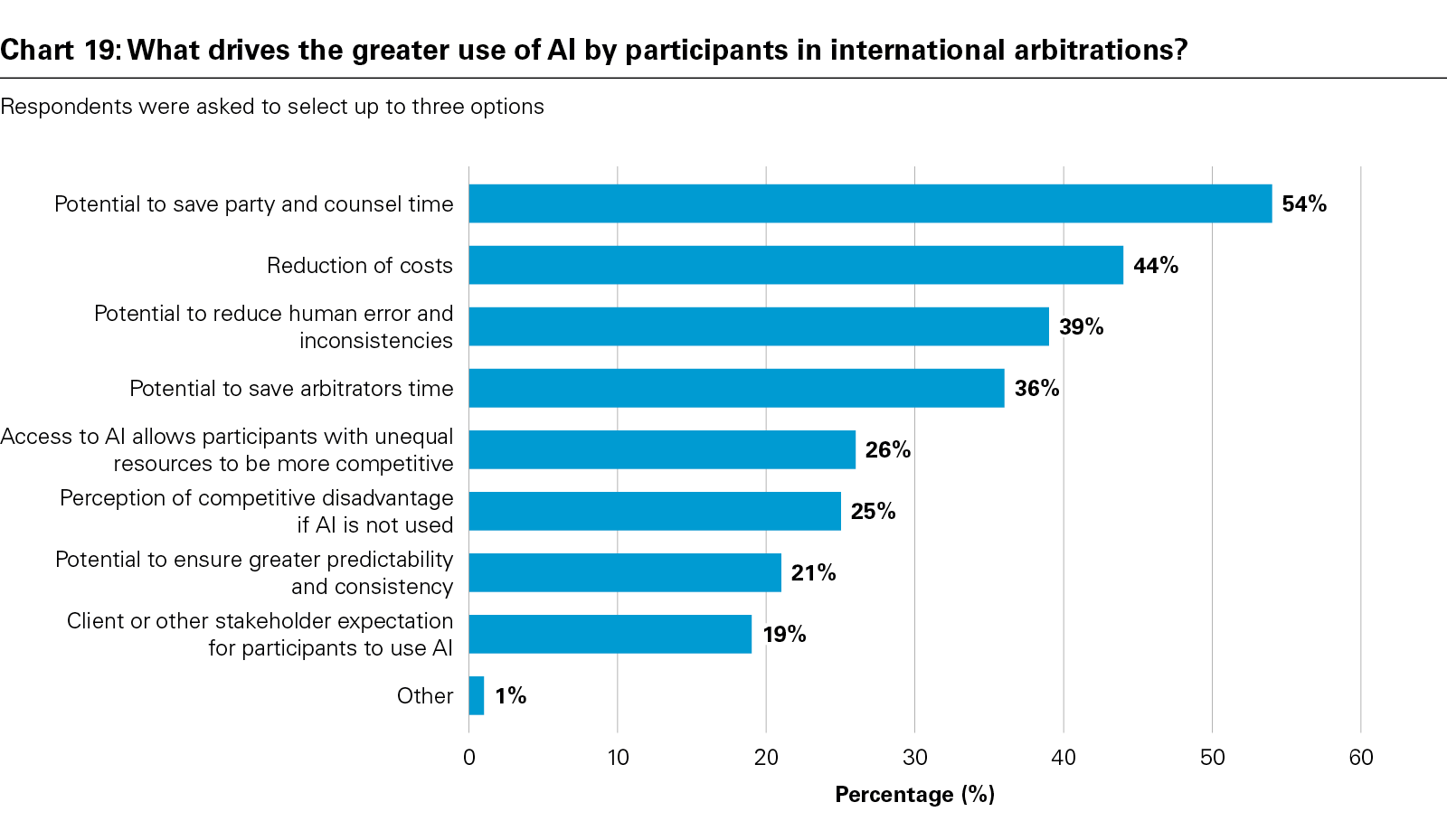

- The principal drivers for the increased use of AI in international arbitration are saving party and counsel time (54%), cost reduction (44%) and reduction of human error (39%).

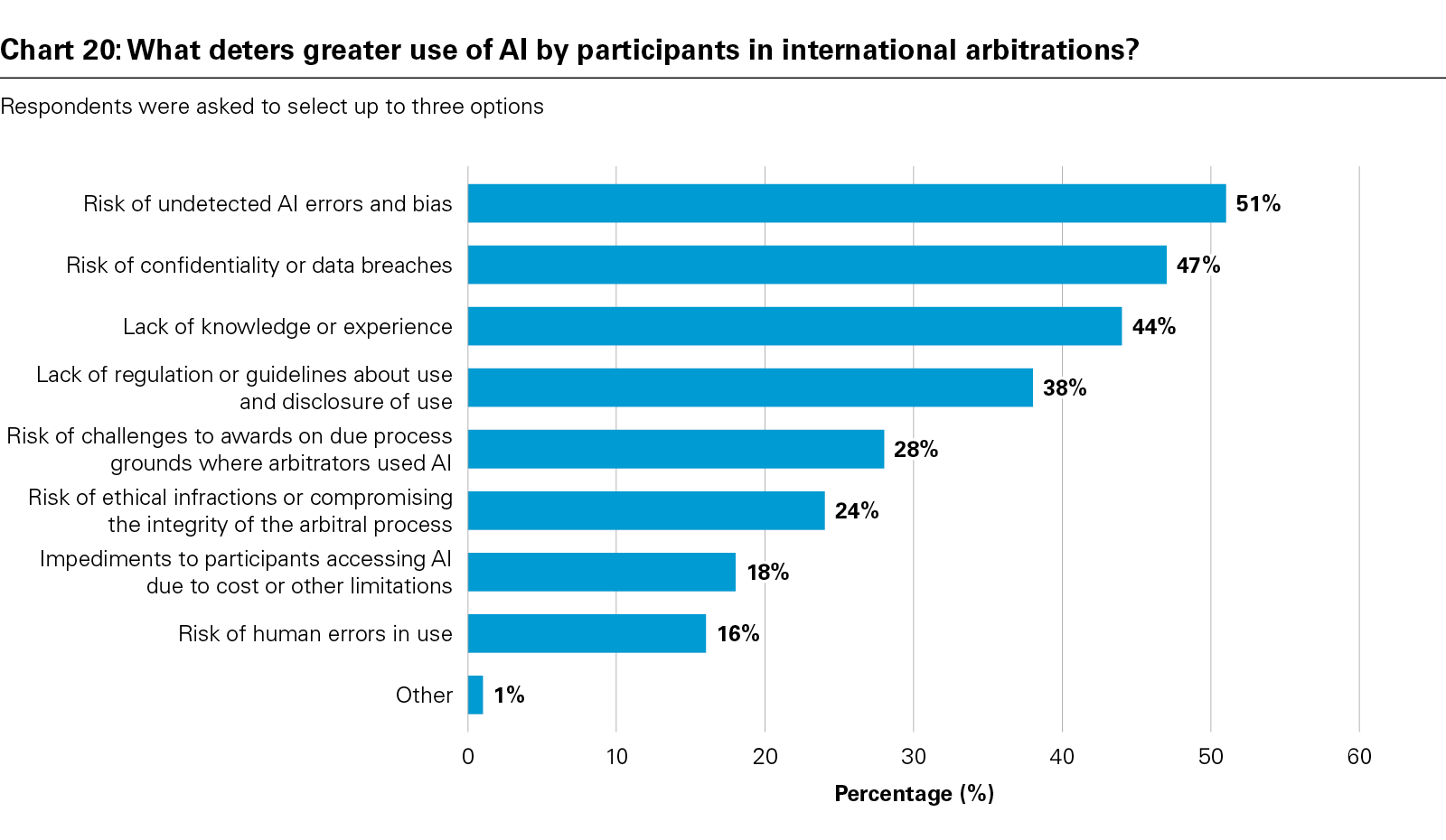

- The principal obstacles to the greater use of AI in international arbitration are concerns about errors and bias (51%), confidentiality risks (47%), lack of experience (44%) and regulatory gaps (38%).

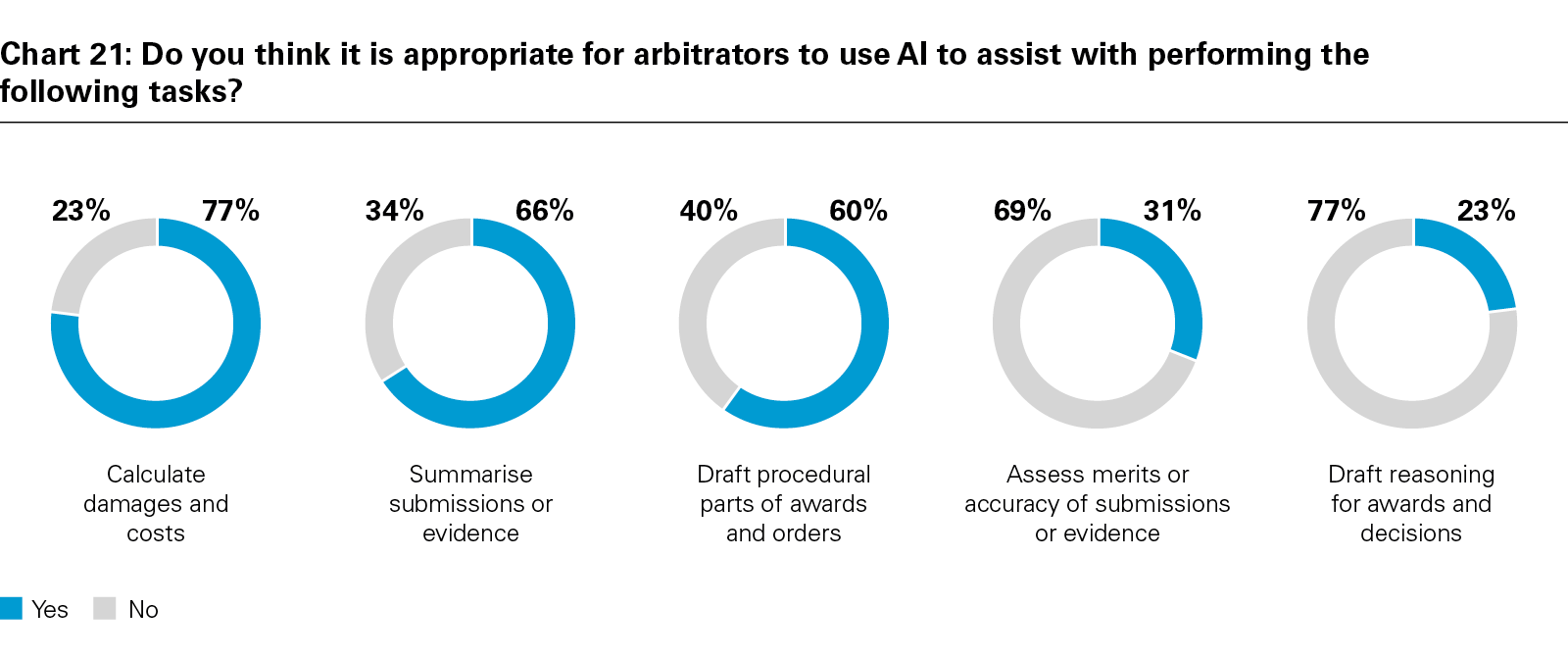

- Respondents largely approve of the use of AI by arbitrators to assist in administrative and procedural tasks. There is strong resistance, however, to its use for tasks requiring the exercise of discretion and judgment, which are fundamental aspects of the mandate given to arbitrators.

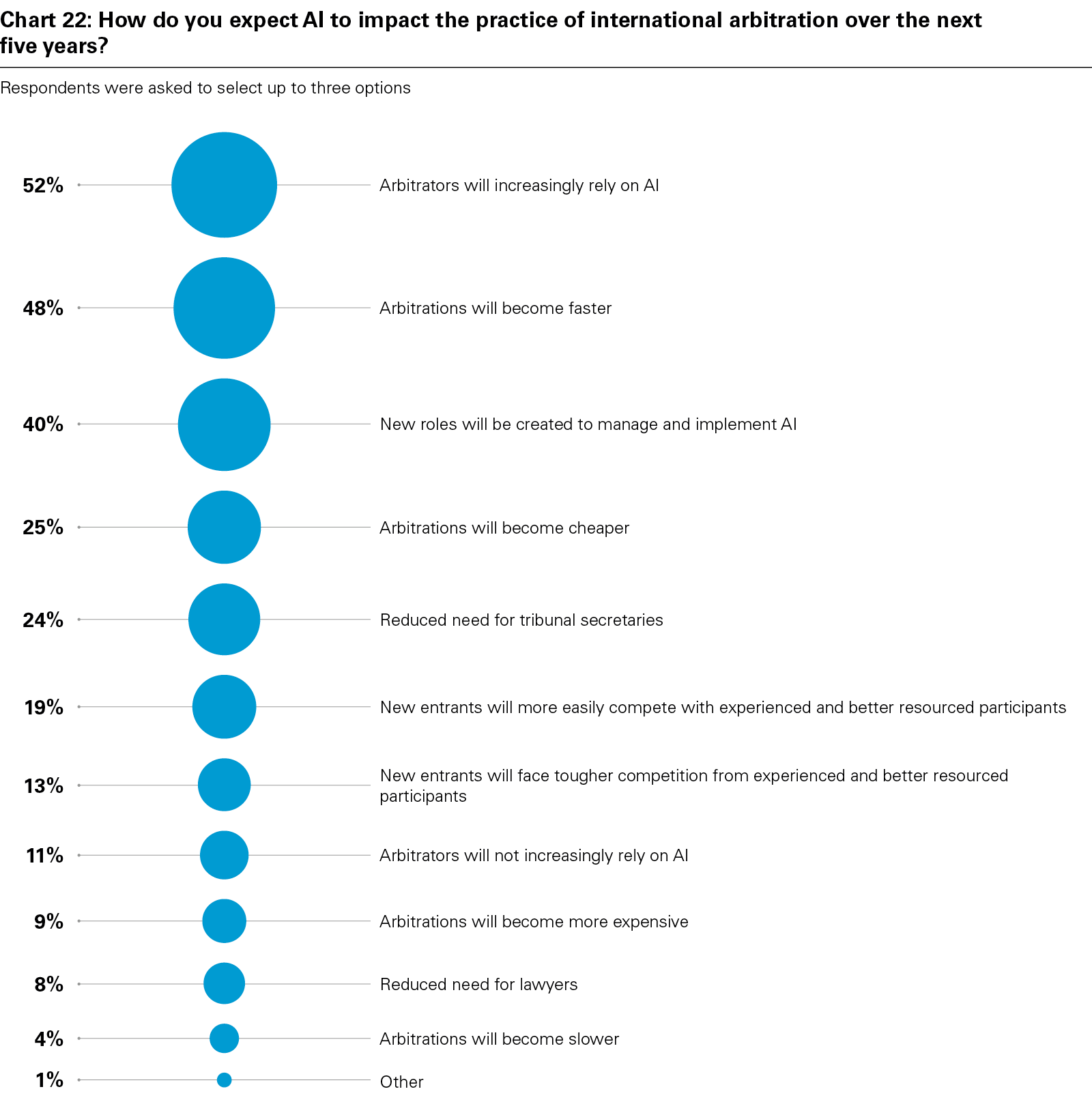

- The general consensus is that, over the next five years, international arbitration and its users will adopt, and adapt to, AI. Respondents predict that arbitrators will increasingly rely on AI (52%) and that new roles to work with AI will emerge (40%). The enthusiasm for greater use is tempered, however, by the desire for transparency, clear guidelines and training on the use of AI.

Acknowledgements

The School of International Arbitration of Queen Mary, University of London would like to thank White & Case LLP for its financial and substantive support, in particular Mona Wright, Julie McCoy and Clare Connellan in London, who coordinated the project on behalf of White & Case and provided invaluable input. We are also grateful for the guidance of Birgit Kurtz in New York and the assistance of the White & Case Business Development, Marketing Communications and Creative Services teams.

We would further like to thank our External Focus Group for their feedback on earlier versions of the questionnaire and methodology, including (in alphabetical order): Mr. Juan Pablo Argentato (ICC), Ms. Nadya Berova (Barrick Gold Corporation), Mr. David Bigge (US Department of State), Ms. Alexandra Couvadelli (Gard), Ms. Olivia de Patoul (Le Bureau), Mr. Werner Eyskens (Crowell & Moring LLP), Ms. Caroline Falconer (SCC), Mr. Karl Hennessee (Airbus), Ms. Martina Polasek (ICSID), Dr. Veronika Korom (ESSEC Business School, Paragon) Ms. Joanne Lau (HKIAC), Mr. Luis M. Martinez (ICDR-AAA), Mr. Maxim Osadchiy (Osadchiy Dispute Resolution LLP; QMUL), Dr. Monique Sasson (Arbitra; DeliSasson), Dr. Laurence (Larry) Shore (Seladore Legal), and Ms. Yukiko Tomimatsu (Nishimura & Asahi).

We are also grateful for the assistance of several organisations and individuals who helped promote the survey, in particular: Africa Arbitration, Arbitral Women, Kluwer Arbitration, Transnational Dispute Management/OGEMID, Global Arbitration Review, Thomson Reuters, LexisNexis, Mr. Jonathan Brierley, Dr. Rémy Gerbay, Professor Emeritus (and Head of SIA) Julian Lew KC, Professor Loukas Mistelis and Professor Maxi Scherer.

Most importantly, we would like to thank all stakeholders (private practitioners, arbitrators, in-house counsel, academics, third-party funders, government officials and other respondents) who generously gave their time in completing the questionnaire and/ or being interviewed.

View full image: Regions in which respondents principally practice or operate (PDF)

View full image: Regions in which respondents principally practice or operate (PDF)

View full image: Preferred seats by region (PDF)

View full image: Preferred seats by region (PDF)

View full image: Most preferred seats (PDF)

View full image: Most preferred seats (PDF)

View full image: Preferred arbitral rules by region (PDF)

View full image: Preferred arbitral rules by region (PDF)

View full image: Most preferred arbitral rules (PDF)

View full image: Most preferred arbitral rules (PDF)

View full image: Enforcement (PDF)

View full image: Enforcement (PDF)

View full image: Efficiency (PDF)

View full image: Efficiency (PDF)

View full image: Chart 18: How often have you used, and do you expect to use, AI tools and technology? (PDF)

View full image: Chart 18: How often have you used, and do you expect to use, AI tools and technology? (PDF)

View full image: Chart 19: What drives the greater use of AI by participants in international arbitrations? (PDF)

View full image: Chart 19: What drives the greater use of AI by participants in international arbitrations? (PDF)

View full image: Chart 20: What deters greater use of AI by participants in international arbitrations? (PDF)

View full image: Chart 20: What deters greater use of AI by participants in international arbitrations? (PDF)

View full image: Chart 21: Do you think it is appropriate for arbitrators to use AI to assist with performing the following tasks? (PDF)

View full image: Chart 21: Do you think it is appropriate for arbitrators to use AI to assist with performing the following tasks? (PDF)

View full image: Chart 22: How do you expect AI to impact the practice of international arbitration over the next five years? (PDF)

View full image: Chart 22: How do you expect AI to impact the practice of international arbitration over the next five years? (PDF)